PA Needs CO2 Limits—and Strong Renewables Policy, Too

New modeling shows that Pennsylvania can remain a large electricity exporter while building a better, cleaner, and stronger economy.

New electric power sector modeling by NRDC shows that Pennsylvania can remain a large energy exporter while building a better, cleaner, and stronger economy if it caps and prices carbon dioxide emissions, increases its renewable energy goals, and strengthens its commitments to energy efficiency. Modeling highlights:

- Absent limits on carbon pollution, emissions from the state's power plants will increase over the next two decades—reversing the decline of the past decade—as both nuclear and coal plants become unprofitable and are replaced by gas plants.

- Carbon limits must be accompanied by stronger incentives for local renewables; otherwise, emission reductions would be achieved almost entirely by shutting down coal-fired power plants, ramping up generation at gas plants, and reducing electricity exports.

- Together, carbon limits, a 30% renewable energy standard, and stronger efficiency programs would reduce the use of the dirtiest power plants, minimize emissions “leakage” to other states, lower household energy bills, and drive investments in local clean power resources, leading to sustained climate benefits for Pennsylvania and the U.S.

***

New modeling conducted by consulting firm ICF for NRDC shows that Pennsylvania can remain a large electricity exporter while building a better, cleaner, and stronger economy. However, this won’t happen unless state leaders take decisive action both to cut carbon pollution in its power sector and to spur the development of renewable energy, like wind and solar. They can do this by adopting policies that address the costs of power plant pollution while at the same time making strong commitments to renewable energy and energy efficiency.

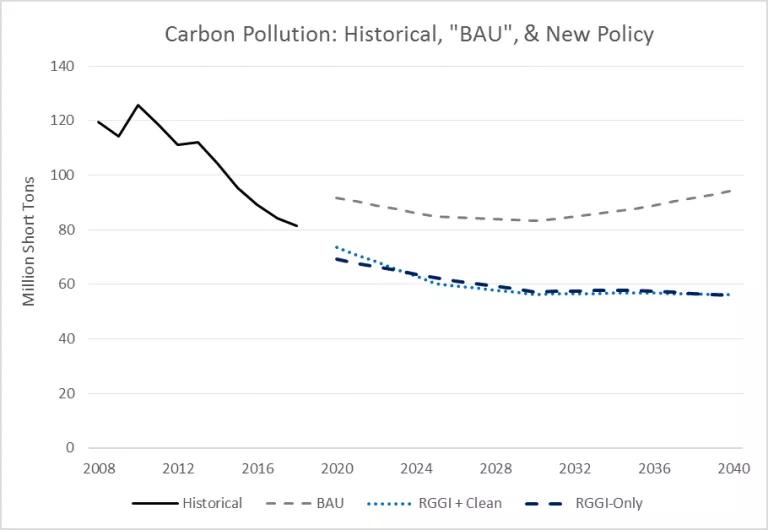

Carbon limits—which would require the state’s power sector to steadily reduce carbon dioxide emissions by increasing plant efficiency and investing in cleaner resources—are critical if Pennsylvania is to make progress on cutting pollution. The analysis finds that without limits, carbon emissions will increase over the next two decades (reversing a recent decline) as both coal and nuclear power plants become unprofitable and are replaced by gas plants. Carbon limits would ensure that the current decline continues.

However, our analysis also finds that unless carbon limits are accompanied by stronger incentives for renewables, emission reductions would be achieved almost entirely by accelerating the coal-to-gas switching that’s happening now and reducing electricity exports. To drive growth in in-state renewables—and realize the job-growth and economic-development potential of that growth—Pennsylvania must also increase the renewable energy goals in the state's Alternative Energy Portfolio Standards Act (AEPS).

NRDC’s analysis is timely because Governor Wolf and the Republican-controlled General Assembly appear to be increasingly interested in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), a regional "cap and invest" policy that limits carbon pollution from the power sector and auctions carbon "allowances," providing states with resources to invest in energy efficiency, renewables, and other consumer benefit programs. Most of Pennsylvania’s neighbors, including New Jersey, New York, Delaware, and Maryland participate in RGGI, which in addition to helping cut carbon pollution from power plants in half, has cleaned up other kinds of air pollution, created thousands of new jobs and lowered energy bills for consumers.

RGGI drives least-cost reductions in carbon pollution by coordinating across states and working in concert with states’ other clean energy policies. In Pennsylvania, though, there is talk of instituting carbon limits in exchange for repeal of the AEPS—the two policies are said to be "duplicative." In fact, our modeling shows that carbon limits and increased renewable goals are complementary policies—and that if the Commonwealth pursues both, along with stronger efficiency goals, Pennsylvanians would see lower electricity bills as well as improved health and well-being.

Modeling: A Planning Tool for the Power Sector

In the power sector world, computer models are used to help forecast and understand the environmental and economic effects of different energy policies. To model the effects of carbon limits and other clean energy policies in Pennsylvania, NRDC asked ICF to model three different policy scenarios using ICF’s Integrated Planning Model (IPM®). IPM is a detailed power sector model commonly used by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), utilities, and state regulators. IPM integrates extensive real-world information about the power sector with projections of electricity demand, fuel costs, and other information to determine the most cost-effective way for the power system to meet customers' electricity needs under different energy policy scenarios. IPM can build new power plants, close existing plants, and ramp generation up and down to meet demand at least-cost.

We asked ICF to model three policy scenarios:

- A "business-as-usual" (BAU) scenario in which Pennsylvania's energy policies remain unchanged between now and 2040. This means that the AEPS goal for renewables and other "Tier I" resources levels off at 8 percent in 2021. No carbon limits are adopted, nor are any changes made to Act 129, Pennsylvania’s energy efficiency standard.

- A “RGGI-only” scenario in which Pennsylvania joins RGGI in 2021, initially capping the state’s pollution at the state’s expected emissions in 2020 (91.7 million tons).The cap then declines by 3 percent per year through 2030. The AEPS and Act 129 are unchanged.

- A “RGGI + Clean Energy” scenario in which Pennsylvania not only joins RGGI (with all the same detail as above), but also raises the Tier I (renewables) goal in the AEPS to 30 percent in 2030, with 10 percent from in-state solar projects (as proposed by Senate Bill 600 and House Bill 1195) and increases energy efficiency savings to 1.5 percent per year, as Senate Bill 232 could do.

For all of these scenarios, NRDC used assumptions about fuel costs, electricity demand, and technology performance and costs based on the latest projections by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Energy Information Administration (EIA) and National Labs. (A full table of assumptions is available here on page 51.)

What the Modeling Shows

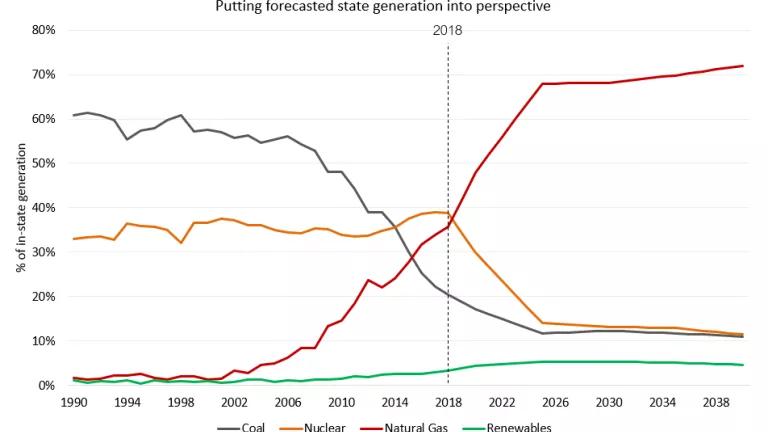

Gas to become the overwhelming source of power without clean energy policy

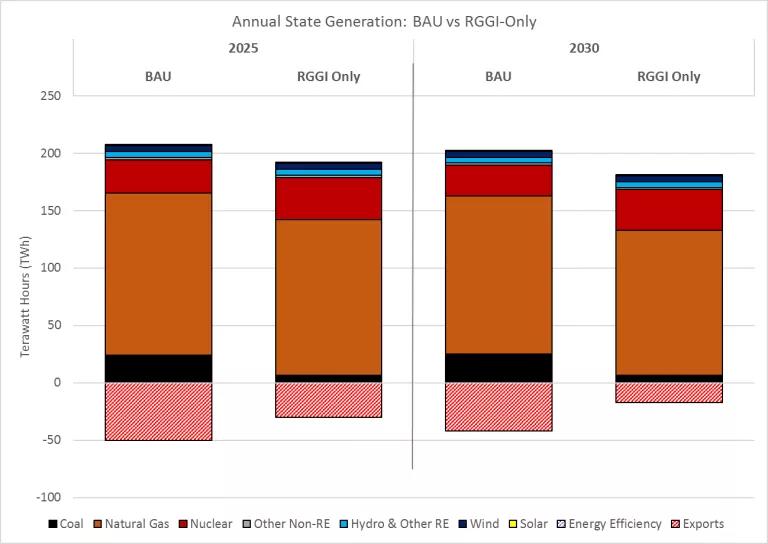

Pennsylvania's fracking boom has drastically changed the state's power sector and will continue to push it toward gas without fairer PJM market rules and state policies to ensure a more diverse and cleaner system. NRDC’s modeling forecasts that, under “business-as-usual,” generation from gas power plants rises to almost 70 percent of all in-state generation in 2030 (double its market share today)—as persistently cheap natural gas squeezes coal’s generation share to just 12 percent and nuclear’s share to 13 percent. At the same time, generation from renewables rises slightly, from 3 to 5 percent.

In this scenario—i.e., under Pennsylvania's current power sector policies—carbon dioxide emissions from the state's power sector increase, from about 81 million tons in 2018 to more than 83 million tons in 2030 and 94 million tons in 2040.

By contrast, participating in RGGI would ensure emissions reductions of 3 percent per year between the year that Pennsylvania enters the framework (2021 in the NRDC analysis) and 2030, when the RGGI states will implement a new phase of emissions reductions, In our modeling, when only those RGGI limits are imposed (with no strengthening of complementary clean energy policies or investment of carbon auction proceeds into clean energy programs), these emissions reductions are achieved mainly by accelerating a transition away from dirtier coal generation. This results in pollution reductions large enough to offset a large increase in gas generation and a small decrease in non-emitting nuclear generation. In-state renewable generation sees little to no change from “business-as-usual,” with just the same slight renewable growth.

There is a better way to achieve lasting pollution cuts

The model shows essentially the same reductions in carbon pollution when, in addition to joining RGGI, Pennsylvania increases its renewable energy goals in the AEPS to 30 percent and increases energy efficiency savings to 1.5 percent per year. (Currently, the efficiency programs run by Pennsylvania's electric distribution utilities under Act 129 achieve reductions of less than 1 percent annually.)

However, increasing the renewables goals in the AEPS has other benefits besides reducing carbon pollution. With respect to public health, the model shows that a strong AEPS achieves greater cuts of in-state sulfur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxide (NO2) emissions—pollutants that contribute to local smog issues and worsen respiratory issues like asthma—than RGGI alone. This means fewer childhood asthma attacks, ER emergencies, and lost work days, and helps mitigate the general health impacts of climate change in Pennsylvania.

Combining RGGI and the AEPS also leads to sustained, measurable climate benefits on a national basis, because investing in non-emitting power in tandem with reducing the use of the dirtiest power plants, minimizes emissions “leakage,” where pollution merely shifts to states without carbon limits. In a RGGI-only approach, some emissions leak to nearby states.

And as we know from the Clean Jobs Pennsylvania reports issued annually by Environmental Entrepreneurs (E2),Keystone Energy Efficiency Alliance (KEEA), Green Building Alliance, Sustainable Pittsburgh and Sustainable Business Network of Greater Philadelphia, growing renewable energy and energy efficiency creates good-paying jobs and boosts economic development and local tax bases (including in more rural areas of the state). When states establish strong renewable energy goals—signaling to businesses an openness and interest in clean energy—they create more renewable energy jobs and a stronger clean energy economy. Modeling for the Pennsylvania DEP's Finding Pennsylvania Solar Future project showed that 10 percent in-state solar goal would result in 60,000 to 100,000 jobs and result in a net benefit of over $1.6 billion annually from 2018 to 2030 from energy savings and infrastructure investments.

In addition to the job-creating benefits of energy efficiency highlighted in Clean Jobs Pennsylvania, NRDC’s modeling highlights another benefit of efficiency: lower electricity bills. At least in the short term, implementation of RGGI is likely to cause a small increase in wholesale electricity rates as power plants first start to internalize the costs of their pollution. However, Pennsylvanians do not pay rates; they pay bills. And their bills are determined not just by wholesale rates, but by how much electricity they use. By reducing energy waste—e.g., through more efficient heating and cooling systems and better insulation—efficiency can help households remain cool in the summer and warm in the winter with lower utility bills than they pay today—even if rates go up. NRDC’s modeling bears this out, showing that by complementing RGGI with both a stronger AEPS and greater investment in low-cost energy efficiency, the average Pennsylvanian’s electricity bill would decrease by about $12 a year in 2030 and about $25 a year in 2040 compared to “business-as-usual.”

RGGI and the AEPS (and Act 129) are Complementary Policies

The modeling performed by ICF for NRDC confirms what we already know, based on the first decade of RGGI. Each RGGI state has strengthened its renewable portfolio standard and energy efficiency programs over this period; they know that carbon limits and technology-based incentive policies serve different purposes, and have seen the huge benefit of complementary approaches to direct our energy markets toward the public goods of clean air and climate change mitigation. This multiple policy approach has also resulted in economic development, job growth, and billions of dollars of investment into their states as well as savings for their residents, businesses and communities.

Declining carbon limits ensure emission reductions. But depending on how stringent a state's limits are and when they take effect, and how carbon-intensive the state's energy mix is, carbon limits may not drive enough investment in the low-carbon energy resources needed to ensure sustainable, longer-term emissions reductions. NRDC’s modeling suggests that this is the situation in Pennsylvania, where, due to very cheap natural gas prices, a RGGI-only approach is likely to cut emissions in the near-term more by increasing generation from gas than from building out renewables to create a stronger clean energy system in the long run. This is why Pennsylvania’s policymakers need to also increase the renewable goals in the AEPS and investments in energy efficiency, in tandem with carbon limits.

Fossil fuel interests argue in Harrisburg that the AEPS "distorts" Pennsylvania's energy market. In fact, the renewable goals in the AEPS rightly direct Pennsylvania’s energy markets to produce more of the low-carbon resources that we need in a rapidly warming world and that Article I, Section 27 of the state constitution arguably requires. Moreover, the AEPS is a market-based mechanism that uses supply and demand to provide the market with a predictable, long-term investment signal that’s critical for renewable energy financing.

In short, Pennsylvania can and should shape its energy markets so that they produce electricity that is not just affordable and reliable, but also clean. The state has an opportunity to do that this fall by adopting carbon limits, and legislating stronger commitments to renewable energy and energy efficiency.

Correction: As originally published, this blog incorrectly stated that NRDC's "RGGI + Clean Energy" scenario modeled energy efficiency savings of 2 percent per year. The blog has been corrected to state that we modeled 1.5 percent annual savings.