The Woodrow Wilson Center and Environmental Law Institute today released a collaborative new study looking at both energy subsidies and U.S. energy flows. (A presentation on the report which includes a comparison of energy flows in 1992 and 2007.) Additional stories on the report are here.

The topic of energy subsidies is a popular one internally, and one we get asked about on a regular basis. Certainly, federal investment in emerging clean technologies which have to struggle against a variety of market and non-market barriers can have powerful societal benefits.

NRDC has long sought to reform how mature fossil fuels and nuclear power get subsidized compared to renewables, for several reasons. One, in their developing phases, the nuclear, coal, gas and oil industries received subsidies an order of magnitude larger than ones renewable technologies are receiving in their early developmental stage. These incentives were vital in driving long-term cost reductions and scale up of fossil and nuclear technologies, and given their societal, economic and environmental importance, renewable technologies should receive a similar kick start. Second, mature energy technologies that have already received hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies should be commercially competitive and able to compete without additional federal support.

However, accurately tracking, quantifying and comparing aggregate domestic energy subsidies and RDD&D (research, development, demonstration and deployment) innovation incentives challenging and can provide an array of different and conflicting conclusions. Many studies calculate massive historical and current nuclear and fossil fuel subsidies, although more recently, renewables have received increasing amounts of support. (For those interested, I highly recommend Doug Koplow's informed and insightful work at Earth Track.)

The WW/ELI study above won't necessarily end the debate, but it does provide a excellent set of data points, and points out a few wrinkles in energy policy.

The stated goal of the subsidy section of study was solely to measure the cost of energy subsidies to the U.S. government, without looking at the value to the recipient. Therefore, outside of quantifying subsidies, no effort was made to determine the impact of subsidies or their relative value based on units of production. Indirectly, the report also seeks to demonstrate which energy technologies these subsidies are targeted to assist "against a backdrop of growing energy and climate concerns".

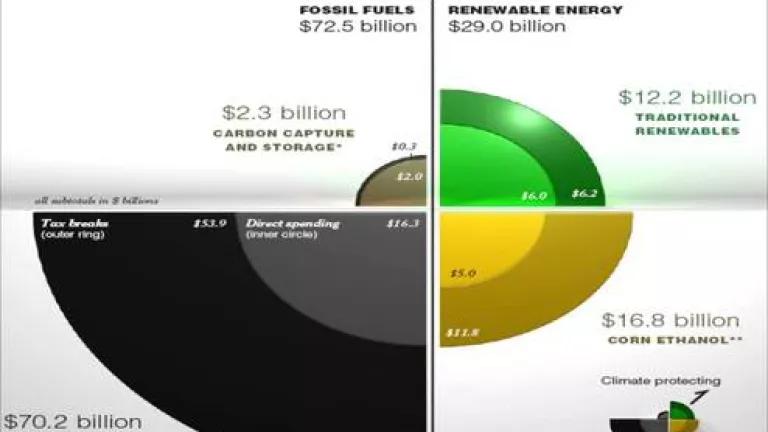

The 1992 study on energy subsidies showed very little spending on renewable energy - $442 million - with $8 billion going to various fossil fuels (excluding the transportation sector). Additionally, only 5% was spent on energy conservation. The updated energy subsidy study seeks to quantify all spending from 2002-2008, and while painting a more promising picture for renewable energy, still demonstrates how extensive the federal support of carbon-intensive technologies remains. A quick summary:

- Total energy subsidies from 2002 to 2008 - over $100 billion

- Most of subsidies still go to traditional fossil fuels - $72.5 billion

- Corn ethanol gets over half of all renewable subsidies - $16.8 billion

- Traditional renewables (excluding corn ethanol) - $12.2 billion

- Largest tax expenditure: Preferential treatment of oil and gas income under foreign tax credit ($15.3 billion from 2002-2008). Second largest expenditure was the credit for production of non-conventional fuels ($14.1 billion from 2002-2007 - now phased out)

This picture alone leads to an obvious conclusion - too many energy subsidies are being provided to technologies we need to move away from, and too few incentives are being allocated towards low-carbon, clean energy.

A few other points from the study are worth noting:

Fossil fuel subsidies tend to be permanent, and very old - some go back almost 100 years. This makes rescinding them extremely difficult, and also demonstrates the fact that much energy policy is based on historical conditions which no longer apply. Renewables tax breaks, however, have been conceived as temporary and tended to sunset quickly. The latter has had an out-sized impact on wind development, where frequent expirations and short-term extensions have led to a boom/bust cycle which has disrupted wind development. Additionally, those projects with a longer development cycle (biomass, geothermal, concentrating solar) have had difficulty finding capital due to the political uncertainty of these tax breaks.

The Pareto Principle certainly applies in this study, as almost $65 billion in subsidies over 2002-2008 can be attributed to 7 policy mechanisms. This is a surprisingly high concentration, given the hundreds of energy incentives and subsidies. Within renewables, two incentives for corn ethanol are responsible for more than half of renewables support (the VEETC, and corn production subsidy payments).

Finally, it is important to point out that there are a number of other energy policy support mechanisms that were excluded from this report, as they weren't defined as a "subsidy" in the report, but have immense value to select energy sectors. These include standards, regulations, and liability limits, such as the Price Anderson Act. The costs (*and benefits*) from these policies tend to be borne by industry, taxpayers or society.