Public Lands Are Not Neutral. We Must Grapple with Their Racist Roots.

Green spaces should feel like everyone’s backyard.

Stanislaus National Forest in the Sierra Nevada mountains

Dreamstime

This essay was produced through the Agents of Change in Environmental Justice fellowship and was originally published by Environmental Health News.

As the sun rose on a summer day in the Bronx during the 1960s, my father boarded a bus with his friends for their annual summer school trip to Bear Mountain State Park in the Appalachians upstate. As a first-generation Nuyorican (of the New York Puerto Rican diaspora) growing up in the South Bronx, he didn’t visit state and national parks because my grandparents couldn’t afford it. This was the one day a year he and his friends spent in the mountains hiking, swimming, canoeing, and playing games, and my dad looked forward to it all year. For the rest of the summer, he spent time outdoors in the city—the South Bronx was his backyard.

Now, a bit more than 50 years later, as a staff scientist for the NRDC focusing on forest ecology and climate change, I find myself wandering around a different national forest every other month with a curiosity I didn’t tap into until graduate school. Growing up, we visited the South Bronx often. The food, noise, loud accents, people that looked like me…it felt like a home I had forgotten about. When we visited dad’s backyard, hikes or camping did not feel like part of the culture. Rather, when I think back to those visits, I remember sitting in my grandmother’s kitchen, eating pizza and asopao. I remember sitting on the plastic-covered couch playing games with my brother while the window-unit air conditioner hummed in the background. I remember looking out of the window from the 20th floor at the street below, where a parked car honked at a vehicle trying to double-park. I remember visiting my Tía Rosa’s apartment, where everyone talked over each other in Spanish at the top of their lungs. I don’t remember thinking about “wilderness.”

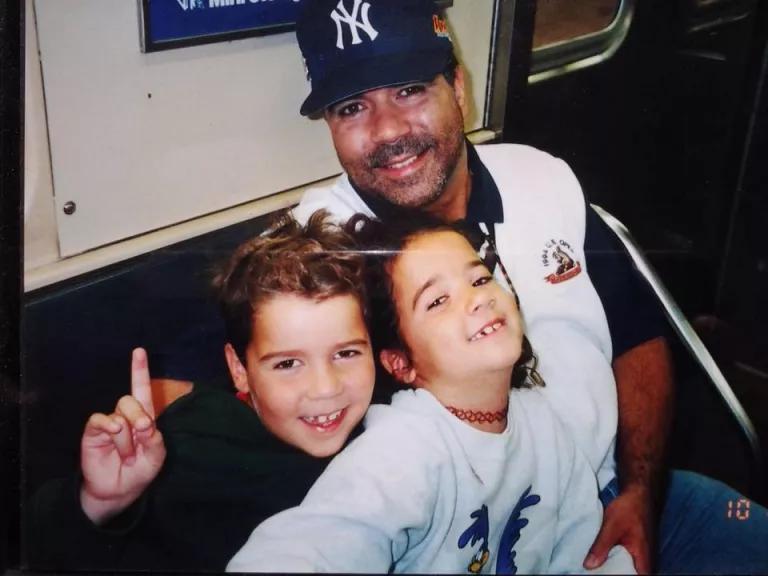

Carolyn in elementary school with their twin brother and father on the subway in New York City

I associated nature much more with whiteness, given my memories of camping as a child in Missouri with my Girl Scouts troop, which was led by my mother, a white woman from Texas. Girl Scout camping trips were some of the most fun I had as a kid, and I treasured those experiences with my mom. But I’m not sure if I brought my whole self or only the part of me that felt superficially normalized by the white community I was a part of. When in parks or forests as a kid, I remember seeing a lot of people who looked like my mom, but not many who looked like my dad. Part of that was due to the demographics of Missouri where I grew up (not a lot of Latines), but now, having lived in many places and traveled to many national parks and forests, I’ve noticed that one thing has remained the same: Most of the people I see out on trails and managing the parks look a lot more like my mom’s side of the family than my dad’s.

Carolyn’s family hiking in Big Bend National Park in West Texas

An analysis of data from the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) shows that white people make up almost 95 percent of the visitors to national forests (77 percent in national parks), despite many forests being located near communities where people belonging to minorities are the majority. On the managing side of the equation, things are not too different: At almost every meeting or excursion I attend for my job, I am the only Latine person represented, and very rarely are there people of color present. The people driving the decisions in the environmental movement, especially around nature conservation, are mostly white and male. As the United States becomes a majority-minority country, federal agencies have started to fear that fewer people will care about public lands because of the primarily white-led stewardship and use of public lands now.

A lot of these racial and ethnic gaps in federal land usage are blamed on indifference or lack of interest from people of color and people of other minority identities, but this viewpoint ignores critical context of how a person’s identities shape their relationship to public lands.

Green spaces should feel like everyone’s backyard. Federal agencies, forest and park managers, and conservationists have to stop believing these are “neutral” spaces. We must grapple with their colonial and racist roots. The viewpoint that our federal public lands system is good as is and that marginalized populations need to buy into it centers colonial and white supremacist structures of land stewardship. Including people from traditionally marginalized backgrounds in public land leadership, like President Joe Biden’s appointment of Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, helps to make this shift from exclusively colonial management to inclusive stewardship. Pursuing comanagement of federal lands with tribes—looking at examples such as state park comanagement in Northern California with the Yurok Tribe—and fostering a deep consideration for what makes people from marginalized communities feel safe would shape a more equitable outdoor experience for all.

Sierra Nevada landscapes Carolyn photographed while on a work trip in central California

The violent history of “neutral” public lands

Recently, my colleague and I visited the Stanislaus National Forest in central California’s Sierra Nevada to learn about the landscape and forest service management. This forest sits on the ancestral homelands of the Sierra Me-Wuk and Washoe peoples, who lived there for at least 8,000 years before European settler colonization. The largest settler impact to the tribes began in the 1840s with the start of the California Gold Rush. Miners and settlers took violent positions toward the Sierra Me-Wuk and saw them as obstacles to their wealth in the “western frontier.” Reports indicate settlers and miners murdered hundreds of Me-Wuk people between 1847 and 1860, and thousands of Indigenous People died before 1870 from a variety of causes, including starvation from forced displacement, massacres, and disease. Colonists also forced Indigenous People into slavery in the Sierra to work in the mines. As a consequence, the overall Indigenous population in California was estimated to have dropped from 150,000 before 1848 to 30,000 after 1870.

This violent legacy echoes throughout the United States, where hundreds of tribes were forcefully displaced. When European settlers colonized these lands, they exhausted the natural and cultural resources that existed in abundance, especially wood. Indigenous People had managed the continent’s vast forests with cultural burns and sustainable wood harvesting for millennia. By the 1600s, colonists began to decimate these forests, often employing Indigenous and African slave labor, adding important context to the relationship many Indigenous and Black people have to forest lands today. By the end of the 19th century, settler farmers and colonial timber companies had completely deforested much of the eastern forests.

As the timber hunger spread west, some settlers began to consider the gravity of destroying natural landscapes and began to advocate for federal protection of forests. They based much of these forest management ideas on German forestry techniques, which relied on “mathematical precision” for “management and exploitation of forest resources” rather than in consultation with Indigenous People who were—and still are—the primary experts on managing these forests. Congress passed the Forest Reserve Act of 1891, which empowered the president to establish reserved forests in the West. President Benjamin Harrison initiated this process under his administration. In 1905, the USFS was officially established under the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Today, the USFS manages 155 national forests and 20 national grasslands, separately managed from the U.S. National Park Service.

Our modern forest landscape would be more barren than it is today if the advocacy that gave rise to the USFS had not happened. However, it is critical to note the colonial and racist historical context surrounding the agency’s formation and the stark lack of input from marginalized groups. The formation of the USFS happened after Civil War reconstruction, amid the ongoing atrocities forcing Indigenous People from their ancestral homelands and while Black people were facing few employment or land ownership opportunities, despite the end of slavery.

Throughout U.S. history, white settlers claimed to revolutionize land stewardship because they saw the preserved ancestral lands of Indigenous People as untouched, wasted capital and refused to acknowledge the human impact that Indigenous People had had on the land for millennia before colonization. The settlers peddled the idea of public lands as being peaceful, neutral places that had been untouched by humans and that would remain so once they realized the environmentally catastrophic impacts of their colonial actions. But these lands weren’t—and still aren’t—neutral and were not untouched by humans before settlers arrived. As I have learned from Indigenous scholars in our current fellowship cohort, the idea of public lands being neutral, wild spaces is actually violent. The ability for settlers to frame public lands in a cloak of neutrality—dismissing the centuries of genocide and conflict that took place there—is an act of violence and erasure of Indigenous life. Neutrality is rooted in safety, lack of conflict, and lack of trauma. For people of color and people of other minoritized identities, public lands aren’t neutral because they hold within them many risks to our personal safety due to the scars of settler colonialism.

Personal safety for marginalized people is not guaranteed on public lands

As a queer Puerto Rican person, I experience challenges working in environmental forest protection that my white, cis-male counterparts will never go through. There are regions of this country where my last name could trigger a request for immigration papers (which I do not need because Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens) or where my presence may be seen as an unwelcome intrusion into an otherwise white-settler-only landscape.

Personal safety largely shapes who visits and manages forest lands. As an ethnically Puerto Rican and racially white person, my whiteness provides a shield against discrimination in these spaces. People of color do not have this protection. Forests and the outdoors hold a deep history of violence in this country against people of color, including murders of Black and brown people outdoors, all at the hands of racist white settlers—from slavery to Jim Crow—by violent means of lynching and other forms of death. “Sundown towns” in the United States were (and many still are) all-white, violently racist towns that pose dangerous threats to Black and all non-white people, especially after dark. The violence targeted at Black people and other people of color in these towns has often been perpetrated at the hands of police. These towns tend to be more rural, posing the risk of racist encounters for people of color when traveling to public lands.

In order to make public lands safer for people of color, we can’t increase law enforcement presence. Most Black people and other people of color do not trust police. That distrust is justified by the racist police brutality throughout American cities. This violence is by no means restricted to cities, as evidenced by the recent murder of Afro-Venezuelan forest defender, Manuel “Tortuguita” Teran, by police in Atlanta. Teran was part of Defend the Atlanta Forest, a coalition protecting the Weelaunee Forest from deforestation and development of a police training facility bordering a majority-Black community. Another forest defender told Democracy Now! that “their passing is a preventable tragedy. The murder of Tortuguita is a gross violation of both humanity and of this precious earth, which they loved so fiercely.”

To make these spaces safer for minorities, we should decrease law enforcement and put those monetary resources into local majority-minority communities to better support community centers, health care, education, and tribal comanagement programs, creating a deeper bond between federal agencies and communities.

When federal agencies lament minimal interest from communities of color in federal land stewardship and engagement, they aren’t considering how people’s identities and lived experiences shape their relationships with that land. As my dad puts it, “not knowing about it [public lands], I didn’t know to miss it.” While we can’t undo history, we can carry this important context into our country’s future of land management and center the marginalized.

This essay was produced through the Agents of Change in Environmental Justice fellowship and was originally published by Environmental Health News. Agents of Change empowers emerging leaders from historically excluded backgrounds in science and academia to reimagine solutions for a just and healthy planet.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

How to Make an Effective Public Comment

From Dams to DAPL, the Army Corps’ Culture of Disdain for Indigenous Communities Must End

A Trailblazer for Tribal Sovereignty