Did you see this eye-catching opinion piece about the polarization in Congress drawn from a new book by a couple of authors who wrote The Broken Branch: How Congress is Failing America and How to Get it Back on Track (which is worth a read as well)? There was another one in the same paper (the Washington Post) about the pathetic track record of the "do-nothing" 112th Congress, specifically noting that the House has failed to launch a real transportation bill. In that piece, Dana Milbank notes that on the other hand the Senate has managed to move some legislation such as transportation in spite of the 60-vote-high hurdle erected before nearly every bill. This kind of action prompted Robert Caro, whose fourth installment of a masterful biography of Lyndon Johnson just rolled out (and who also wrote this great biography of Robert Moses, highway-builder) to praise Senate Majority Leader and former pugilist Harry Reid on his work at the helm of that unruly chamber.

As the two chambers go to conference, it's worth reiterating what's at stake here: Can Congress solve big problems anymore?

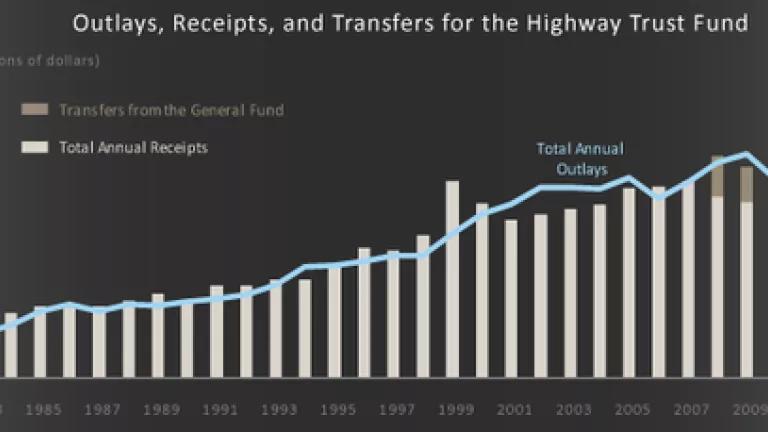

There's a list unresolved and massive problems facing the nation. Our debt and deficit. Economic growth and inequality. Transportation belongs on that list as well. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) underscored this fact with a new report this week about the highway trust fund. This policy tool has seen better days. Revenue shortfalls are chronic, with needs outpacing funding, so much so that more than $61 billion has been transferred from the Treasury to prop it up, as you can see from the graph below (which for some reason excludes Recovery Act funding transferred for transportation and therefore only covers the $35 billion shift made by Congress in 2008).

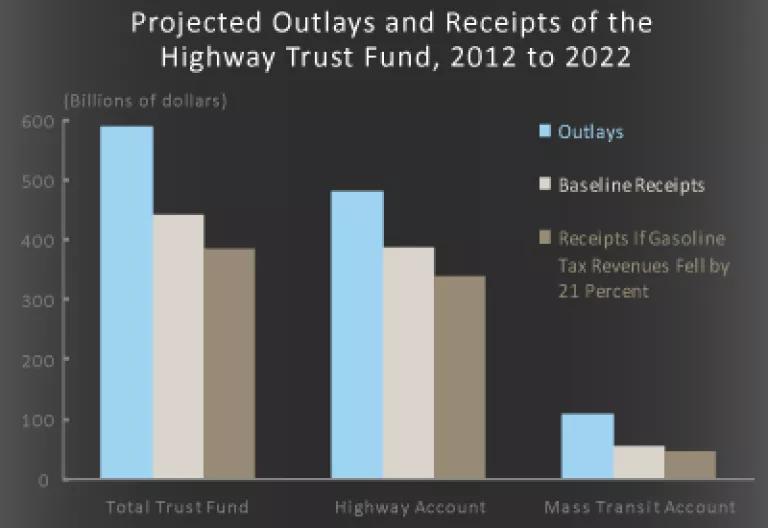

This is projected to get worse over the next ten years, especially since we now have highly effective, world-class fuel economy performance standards in place. The bar graphs below tell the story. The first, huge drop is due to shortfall not counting fuel economy standards. The second smaller one projects the effect of lower gasoline (and therefore oil) dependence due to fuel-efficient car and truck technology.

Leaving this unaddressed is irresponsible, to say the least. The Senate's transportation bill would have spanned two years and maintained current funding levels. It's financed by a variety of fiscal offsets and by an additional transfer from the general fund. It includes policy reforms that should reduce costs, such as prioritization of current infrastructure repair (when you have a tight budget and a choice between repairing a deteriorating foundation or building an addition it's clear the former is the fiscally responsible choice) program consolidation and new performance management requirements. Thanks in part to House inaction, delay in enactment of their bill means it covers less than two years. And it kicks the can down the road on the broader infrastructure financing questions raised not just by the graphs above but by multiple, credible reports such as this one and this one.

At least it patches the hole, puts policy reforms in place, and takes the program through a contentious election year with reliable funding that eludes states and contractors as construction season gets rolling.

The House, meanwhile, competes with North Korea in its fecklessness and inability to launch anything serious. First Speaker Boehner announced his infamous "drill and drive" scheme for financing transportation, something decried as stupid policy by groups as disparate as NRDC and the Competitive Enterprise Institute. I also doubted it would help with revenue given the size of the shortfall and the lag time before drilling revenue might trickle in, and sure enough CBO confirmed that it is a laughable revenue source.

Nonetheless, House Leadership decided to roll out H.R. 7, a partisan bill that was widely decried as the worst transportation bill ever. House GOP leaders then revealed just how they planned to paper over the huge gap left by paltry revenue from new drilling: Kicking the mass transit account out of the highway trust fund, effectively declaring war on public transportation.

As with the assumption that drill and drive was a revenue cure-all, it became clear that House Leaders are "ready, fire, aim" kinda guys. Even with an impressive majority of 242 Republicans vs. 192 Democrats the "whips" who count votes informed leaders that support fell well short of the magic number for passage (218 yea votes). Some Republicans balked at the spending involved. Some -- especially in transit-dependent suburbs of Chicago, New York and Philadelphia -- rebelled at the radical transit account move.

And so, in another radical move the House split the bill into three, presumably hoping that they could cobble together three majorities more easily than one. Party-line votes were then held in three separate committees, and then the drilling package passed the House first. All that remained were the transportation and finance bills. Guess what? There was no way to get to 218 on either of those pieces, whips found out.

One thing to remember is that in committee or more broadly with the whole House the majority party could have reached across the aisle to hammer out policy and "git 'er done" as Larry the Cable Guy says. Sadly bipartisanship and policymaking are not priorities for House Leaders, as the New York Times noted recently.

So now the House comes to conference committee with an empty shell in hand (with three controversial add-ons). It couldn't get the job done. In fact, today while sifting through provisions undermining environmental reviews tacked onto the House husk-of-a-bill I realized they not only eviscerate procedures put in place pursuant to the National Environemntal Policy Act, they could also undercut Clean Air Act protections that reduce tailpipe pollution! The House bill isn't a jobs or investment bill; it's a political exercise.

It's time for Congress to do their job, so contractors across the nation can keep theirs and so we can keep the economy moving. And then we can pivot to developing an overdue long-term solution to our transportation finance challenge. The simple truth is that right now Congress must set politics aside and pass the Senate transportation bill.