Forty years ago this summer, I traveled through the Greater Canyonlands for the first time. I had just finished graduate school and decided to hit the road with friends. We had plenty of adventures along the way, but nothing prepared me for the redrock landscapes of Southern Utah.

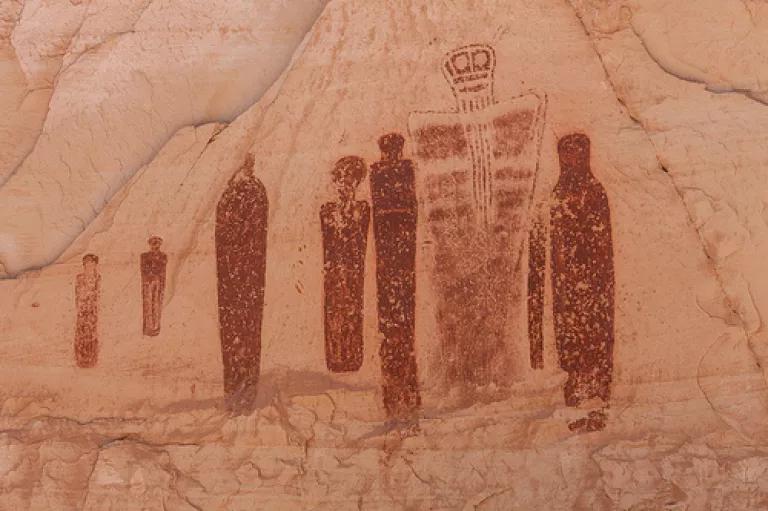

Growing up in the Northeast, I had never seen anything like this stunning place. I was struck by the graceful arches that seemed to be sculpted by a giant’s hand. I loved walking through mazes of deep, narrow canyons where crimson walls rose five stories high. And I admired the rock art left behind by people who lived thousands of years ago.

I had the opportunity to enjoy this pristine beauty because our nation had the wisdom to protect it.

Three Republican presidents and one Democrat helped establish Arches, Bryce, Zion, and Capitol Reef National Parks, and Congress voted to enlarge most of them. Just 10 years before I arrived in Utah, Canyonlands National Park had been created.

These wonders were protected because generations of Americans have agreed on a fundamental idea: conserving wild places makes our country stronger. It sustains the rugged and independent spirit woven through our history.

Over time, safeguarding natural heritage has become an American tradition.

In the case of Canyonlands National Park, however, it’s a tradition left incomplete. More than 50 years ago, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall flew over the region with the head of the Bureau of Reclamation, who wanted to build a massive dam at the confluence of the Colorado and Green Rivers. But when Udall looked down over the canyons and mesas, he couldn’t imagine industrializing them. Instead he exclaimed, “Goodness sake, that’s a national park!”

Udall proposed a national park that would include one million acres. But uranium mining and other companies pushed back, and Congress whittled it down to just less than 260,000 acres—about a tenth of Yellowstone National Park.

Now 50 years later, the area left unprotected is under threat from drilling for oil and gas and strip mining for tar sands oil. The terrain is pockmarked with pump jacks, drill rigs, chemical tanks, and ponds holding toxic waste from wells. Outside one Canyonlands entrance, a company cranked out roughly 700,000 barrels of oil in 2012 alone.

The United States is already the largest oil producer in the world, surpassing Saudi Arabia and Russia according to the International Energy Agency. We have more sustainable resources coming online every month. We don’t need to sacrifice our last wild places to power our economy.

We can protect them. We can call on President Obama to create the Greater Canyonlands National Monument using the Antiquities Act—the same law presidents used to establish four out of five of Utah’s national parks. This designation would finish what Secretary Udall started and honor the American tradition of conserving one-of-a-kind places.

People from all walks of life support this step, from local ranchers to Native American tribes to Latino leaders to the small business owners who benefit from the nearly $300 million national park visitors spend in two counties near Greater Canyonlands annually. The support reaches beyond the region to the many Americans who recognize how fortunate we are to have this natural wonder in our care. You can add your voice to the call to protect Greater Canyonlands by clicking here.

Forty years ago, I felt the magic of exploring redrock canyons far from the crush of civilization and industry. These places remained wild because previous generations understood that some places are too special to drill or dam. Let us do the same for our children and grandchildren.

Photo credits: Bruno Monginoux; Greg Willis