Food matters. And not just because we all have to eat. Or because today is national Food Day.

Food matters because what food we choose to grow, how we grow it, and who makes those decisions has a profound impact on our communities: the air we breathe, the water we drink, the land used to produce that food, the people who grow and harvest it, and the food animals we raise. That reality means we have a right—and possibly an obligation—to think seriously about what kind of a food system we can reasonably expect our governments and corporations to support and then to use our power as citizens and consumers to push them to support it.

But marshaling that kind of people power requires knowing what’s possible. Could our food system look dramatically different from what we see today, while still producing enough food to feed us and remaining profitable?

Researchers at the USDA think so. And reading about their work got me way more excited than you’d think was possible reading an academic paper called Increasing Cropping System Diversity Balances Productivity, Profitability and Environmental Health.

Here’s why.

Looking at three different cropping systems over eight years, the study’s authors found that we can use crop diversification and smart, ecologically-integrated farming techniques to significantly reduce the use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides—and the resulting environmental pollution— in conventional agriculture while still maintaining yields and profits.

The study itself is a technical read but not insurmountably so. And it includes some knock-out graphs, if you’re into that sort of thing. But just in case you’re not, here’s my quick summary:

The researchers examined the impacts of 3 different cropping systems on Marsden Farm in Boone County, Iowa:

- A conventional 2-year corn-soy rotation, which received fertilizers and herbicides at rates comparable to those used on surrounding commercial farms.

- A 3-year rotation that rotated oats in with corn and soy and planted red clover in the winter, which was managed with reduced synthetic nitrogen fertilizer and herbicide inputs and periodic applications of composted cattle manure.

- A 4-year rotation of corn, soy, oats, and alfalfa, the latter planted as feed for livestock, with cattle manure then used as fertilizer. This final system was likewise managed with reduced synthetic nitrogen fertilizer and herbicide applications.

In the latter two systems, rather than completely eliminating the use of chemical inputs, the researchers applied herbicides and pesticides only when necessary and in low, precise doses, not routinely and over large areas, as is typical of conventional farming.

The authors tracked the performance of the three systems over a “startup” phase of the study (2003-2005) and what they termed the “established” phase of the study (2006-2011), tracking the following variables for each:

- Corn yield

- Soy yield

- Total harvested crop biomass

- Profitability

- Synthetic nitrogen fertilizer inputs

- Herbicide inputs

- Energy inputs

- Labor inputs

- Viable weed seeds (as a measure of effectiveness of weed suppression)

- Weed biomass (as a measure of effectiveness of weed suppression)

- Toxicity potential (defined as freshwater toxicity based on the ecotoxicological profiles for the herbicides used)

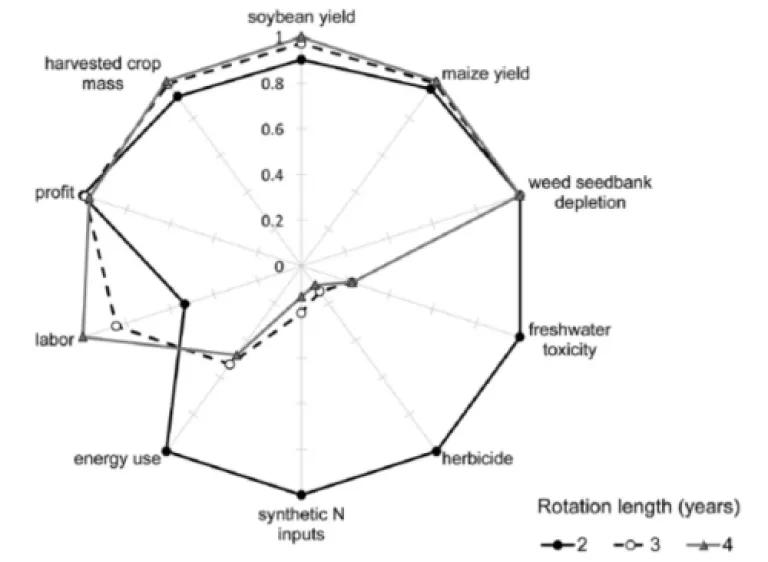

The results are best summed up by this absolutely terrific graph:

But once again, if you don’t feel like staring at a graph, here’s what they boil down to:

Yields and profits stayed steady across all systems. The researchers found that cropping system diversification enhanced yields of corn and soy grain, as well as system-wide harvested crop biomass (grain, straw, and hay), all while maintaining profitability. Net profits were analyzed across both the startup and established phases and found to be no different between the three cropping systems during either phase. In addition, the authors analyzed impacts on “stability of system performance over time” (not on the graph above) and found that cropping system diversification was associated with lower variance in profit during the established phase of the study—i.e. fluctuations in profit between 2006 and 2011 were lower for the 3 and 4-year rotations than in the 2-year conventional system.

But that’s not all.

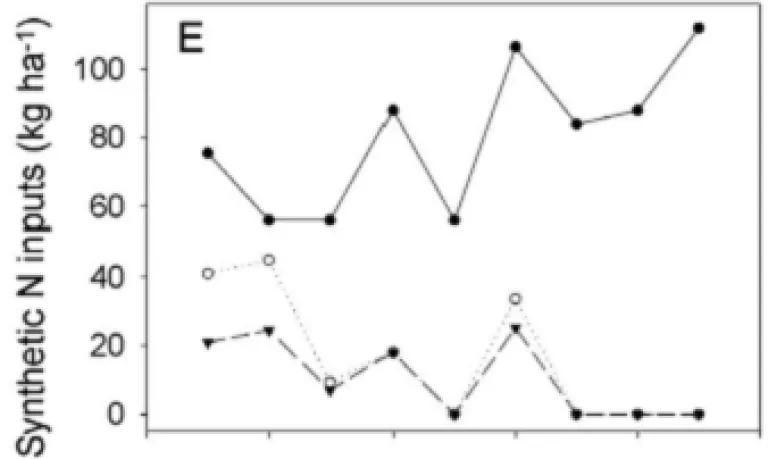

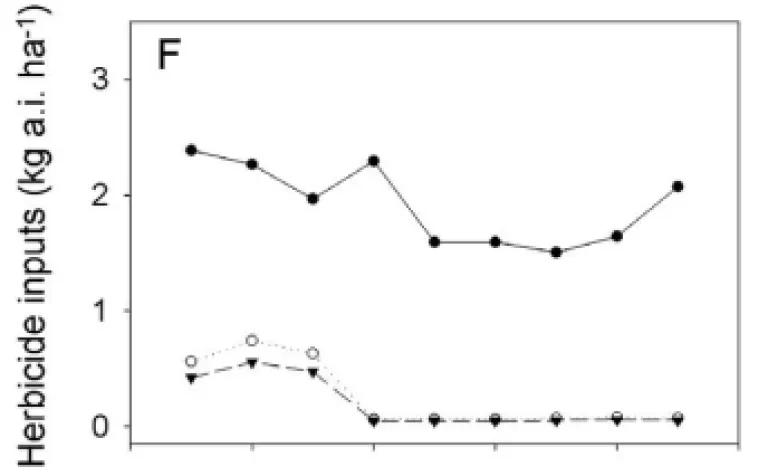

Chemical inputs came way down in the diversified systems, while keeping weeds under control. Here, the results were truly striking. Nitrogen fertilizer applications were higher in the 2-year rotation than in the 3-year and 4-year rotations from the start, but the difference between systems increased dramatically over the course of the study.

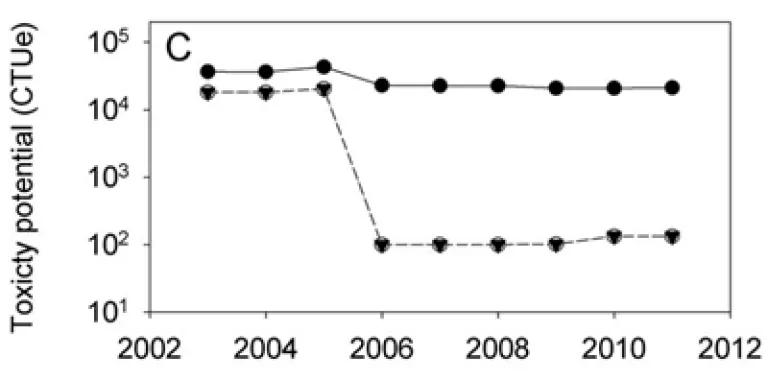

And toxicity in surrounding water came way down too. From the start, environmental toxicity was lower in the more diverse rotations compared to the conventional system. But that difference grew as the systems matured, going from a two-fold difference during the startup phase to a 200 hundred-fold (!) difference in the established phase.

As Adam Davis, one of the USDA researchers associated with the study explained,

“We wanted to show that small amounts of synthetic inputs are very powerful tools, but they’re tools with which you tune the system, not drive it.”

The only area where the conventional system needed less of an input was on labor. It turns out that under conventional management practices, chemicals effectively replace labor. But as the study suggests, reversing that trend by ramping down chemical use and putting more people to work in our rural communities wouldn't have to negatively affect yields or farm profits. That's a trade I'd be willing to make.

Bottom line? As I discussed here, we need to get beyond pitting big agriculture against small agriculture and start moving towards better agriculture. A back-to-the-future approach that blends the best of traditional, diversified cropping systems and targeted uses of modern agrichemical inputs could offer a powerful, forward-looking roadmap for agriculture that could transform how we produce food in the United States and around the world.

That’s exciting news on this Food Day.