Last week, while many of us here in New York City faced the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, the National Wildlife Federation released its roadmap for increased cover crop adoption, laying out a plan for achieving 100 million acres of cover crops by 2025.

I had the pleasure of contributing to the roadmap and am thrilled to have this resource to inform the work of NRDC’s team of food system reformers, but first thing’s first: What is cover cropping, why does it matter, and what does any of it have to do with monster hurricanes?

In its basic form, cover cropping refers to the farming practice of planting a second, non-commodity crop in coordination with a main crop to provide cover to fields during parts of the year when they’d otherwise be left bare. Under a traditional cover cropping approach, a farmer would grow cover crops not for sale, but to protect and improve his or her soil health during the off-season.

Unfortunately, most U.S. cropland is not being cover cropped. Typical commodity crops, such as the corn and soy crops that dominate the Midwest, cover the soil for only a few months of the year. After harvest and before the next spring planting, bare soils are exposed to erosive rains and wind for up to nine months.

Months without plant cover, combined with the need to replace lost nutrients with chemical inputs and heavy tillage in most field crop systems, means these monoculture farming systems without cover cropping also generate large amounts of the heat-trapping greenhouse gas emissions that are warming our planet.

Here in the Northeast, we got a heavy dose of what life on a warming planet looks like last week: bigger, more intense, and more frequent storms that leave a trail of destruction in their wake that will likely take years and billions of dollars to recover from.

The painful wake-up call provided by Sandy has focused attention on how global warming is heating up our oceans, loading hurricanes and other storms with extra energy, making them more violent, increasing the amount of rainfall and high winds they deliver, and making flooding more likely and severe.

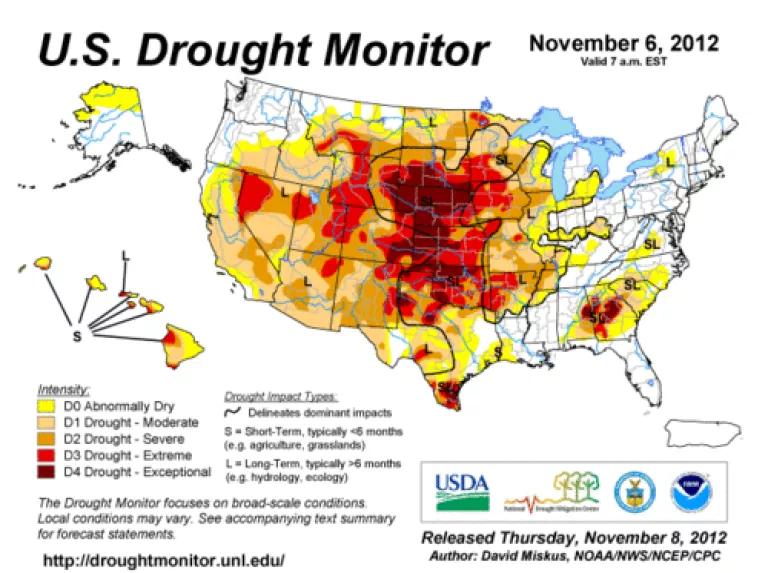

As my colleague Margaret described here, last week, New Yorker’s realized the fragility of the infrastructure on which we depend when faced with this level of natural fury. But we weren’t alone this year in wondering how extreme weather would impact our communities. The largest drought in more than 50 years hit Midwestern farmland hard this past summer, leading many to worry equally about the resilience of our food system in the face of a rapidly changing climate.

Against this backdrop, healthy soils are emerging as the underpinning—the key “infrastructure”—of an agricultural system that not only helps mitigate global warming, but is itself more resilient to extreme weather events, as my colleague Claire discussed here.

A critical part of reinforcing that infrastructure is having vegetation growing year-round. Vegetation helps hold moisture in the soil. The leaf canopy of cover crops shields the soil from rain and wind, provides habitat, and supplies green matter to either nourish the soil or be harvested. The crops’ roots hold two-thirds of the carbon of the plant, and provide numerous benefits to soil quality. When fields are bare, these benefits are lost.

Keeping crops growing year-round also increases the amount of carbon dioxide absorbed from the atmosphere during photosynthesis. In addition, by reducing erosion and preventing the soil from becoming exposed, cover crops help keep carbon stored safely in the soil. This makes cover cropping an important strategy in mitigating global warming.

And as the NWF roadmap explains, cover crops retain nutrients that would otherwise leave the field via runoff, leaching, or evaporation, making those nutrients available for the next crop. By keeping soils covered, cover crops significantly reduce nutrient runoff and associated water pollution, as well as emissions of nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas more than 300 times more powerful than carbon dioxide.

In short: cover cropping leads to more resilience, more carbon sequestration, and less nitrogen pollution.

[Photo by Gabe Brown, NRDC 2012 Growing Green Award Winner, as published in the NWF Roadmap.]

But that’s not all. As I discussed here, there’s also a bottom line benefit to building soil health with a diversity of crops: a sharp drop in the need for chemical inputs like fertilizer and herbicides without sacrificing yield in cash crops.

A recent study out of Iowa has given a needed boost to this idea, demonstrating how farmers can use crop diversification and smart, ecologically-integrated farming techniques to significantly reduce the use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides—and the resulting environmental pollution— in conventional agriculture while still maintaining yields and profits. Cover cropping can and should factor in to this “back to the future” approach to farming.

Cover cropping alone may not be a silver bullet; likely, no one farm practice can be. And as Tom Laskawy discussed here, there are multiple barriers—economic, political, cultural, and even generational—to scaling up the agriculture we need. But each year it becomes clearer that we must make changes to our infrastructure all around, from our densest coastal cities to the fields of our Heartland. It won’t be easy, but the costs of business as usual make it imperative that we get started. By setting ambitious but achievable goals for cover crop adoption and laying out a credible plan for achieving them, the NWF roadmap makes an important contribution to this effort.