Hurricanes and Climate Change: Everything You Need to Know

The most widespread, damaging storms on earth are getting worse, and climate change is a big reason why. Here’s a look at what causes hurricanes and how to address the threat of a wetter, windier world.

Linda Rodriguez Flecha/AP

Pounding rain, raging winds, and devastating storm surge. When hurricanes make landfall, they bring a trifecta of threats that are capable of leveling communities and destroying lives and livelihoods. Named after the ancient Taíno trinity god of storms, Huraca'n, hurricanes are giant energy powerhouses. Here’s a look at what they’re made of, how climate change is affecting them, and how to limit damage from their wrath.

Hurricane facts

What is a hurricane?

A hurricane is an intense low-pressure weather system of organized, swirling clouds and thunderstorms that gain energy from warm tropical waters. While we’re using the term hurricane here, these systems are actually identical to typhoons and cyclones— the name varies depending on where they originate from. They’re called hurricanes in the Atlantic basin and in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean; typhoons in the northwestern Pacific; and cyclones in the Indian Ocean and South Pacific (more on this later). To be classified as a hurricane, wind speeds must reach at least 74 miles per hour (mph). That’s powerful enough to peel off roof shingles.

With their distinctive buzz saw shape when viewed from above, hurricanes spin around a low-pressure center known as the eye—an area of calm and sometimes even clear sky. Journalist Edward R. Murrow, who flew through the eye of 1954’s Hurricane Edna, described it as “a great amphitheater, round as a dollar…a great bowl of sunshine.” The eye, which is typically 20 to 40 miles across, is surrounded by a circular “eye wall,” a dense wall of clouds and thunderstorms containing the most violent wind and rain. Beyond the eye wall and extending for as much as hundreds of miles, slowly rotating rain bands bring their own intense thunderstorms, capable of producing fierce winds and tornadoes.

Hurricane categories

Meteorologists measure a hurricane’s strength based on the intensity of its sustained wind speeds and rate it using the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. There are five categories of hurricane: a category 1 produces sustained winds of at least 74 mph, a category 2 storm begins at 96 mph, and a category 3—considered “major”—has winds of at least 111 mph. Categories 4 and 5, which are both considered “catastrophic,” generate winds of at least 130 mph and 157 mph, respectively.

The category of a hurricane reflects only the wind speed, not the overall potential for damage. In fact, the greatest risk comes from flooding associated with the storm surge and/or the intense rains the storms generate. Consider Superstorm Sandy, which arrived in New Jersey with 80 mph winds (barely over the category 1 minimum) but still proved devastating. Sandy lacked the extreme winds of a major storm, but the massive swell of water it generated crashed into New Jersey and New York, obliterating beaches and boardwalks, filling subway tunnels, inundating neighborhoods, and destroying massive amounts of infrastructure. Similarly, most of the damage caused by hurricanes Florence and Harvey were largely attributable to torrential rains, not wind or even storm surge in coastal areas.

Hurricane season

For the Atlantic basin (comprising the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico), hurricane season runs from June through November. The Atlantic season peaks between mid-August and late October; in the past, a typical season would produce an average of 6.2 hurricanes a year, but now it can produce an average of 10 hurricanes—with more than a third of them measuring category 3 or above.

Hurricane season in the eastern Pacific, an area extending from the U.S. West Coast to 140 degrees west longitude (about due south of Alaska’s eastern border), lasts from mid-May through November. An average of 12 hurricanes a year appear in the eastern Pacific, with half of them measuring category 3 or above. The central Pacific, which includes Hawaii, typically sees two to five hurricanes a year during its season—June through November—with most storms appearing in August and September.

An average of two hurricanes make landfall in the United States in a typical year, according to data from 1851 to 2020, with an average of three major hurricanes pummeling the coastline every five years. About 40 percent of all hurricanes make landfall in Florida, while 88 percent of major hurricanes hit either Florida or Texas. Between 2009 and 2016, there was an unusually quiet period with few storms, but in recent years, there has been a sharp uptick, with 18 storms making landfall in the United States just between 2020 and 2021. That includes Hurricanes Ida and Laura, which both made landfall in Louisiana with 150 mph winds.

How is a hurricane different from other storms?

The fact that hurricane, typhoon, and cyclone are all used for the same weather phenomena can be confusing. This explains where (and when) they occur, and how they’re different from other major rain and wind events.

Typhoon

A typhoon is a tropical cyclone that occurs in the northwestern Pacific basin, covering eastern and southeastern Asia and Micronesia. Nearly one-third of the world’s big storms develop here, with an average of 26 typhoons a year, mostly between May and November. The world’s largest recorded tropical cyclone was Super Typhoon Tip, which produced winds of 190 mph and measured a massive 1,380 miles in diameter, about the distance from New York City to Dallas; by the time it made landfall in Japan, winds had decreased to 129 mph. The strongest landfalling tropical cyclone on record was Super Typhoon Goni, which slammed into the Philippines with 195 mph winds.

Cyclone

A cyclone—or a “tropical cyclone” or “severe tropical cyclone”—occurs in the Indian Ocean and South Pacific. Cyclones generally occur from May through November in the northern Indian Ocean and between November and April in the southern Indian Ocean and South Pacific. Areas impacted by cyclones include Southeast Asia, northern Australia, the South Pacific islands, India, Bangladesh, and some parts of East Africa, including Indian Ocean islands such as Mauritius and Madagascar.

Tornado

Although both types of storms are known for their spiraling, violently destructive winds, the similarity between tornadoes and hurricanes ends there. A hurricane forms over tropical waters and can span several hundred miles, last for days to weeks, and be predicted well in advance. A tornado, on the other hand, forms over land as a tall, rotating column of air that extends from the base of a thunderstorm (including those produced by hurricanes) to the ground. The largest tornadoes are just over a quarter mile wide and typically last for no more than an hour, though they can pack a punch in terms of wind speed—as high as 300 mph. (Most hurricanes top out around 180 mph.) And advance warnings for tornadoes, while incredibly accurate, are typically less than 15 minutes.

Monsoon

Similar to a hurricane, a monsoon can produce torrential rains that lead to damaging floods, injury, and death. But while a hurricane is basically a single weather event, a monsoon is a seasonal change in the prevailing winds that move from ocean to land—and vice versa—and can produce months of wet (or even dry) conditions. Although most often associated with Southeast Asia, monsoon winds exist around the world, including the U.S. Southwest.

Hurricane impacts

Hurricanes leave a trail of devastation in their wake, piling up costs in terms of lives and livelihood. Here are some of the ways these storms impact communities and the surrounding environment.

How hurricanes impact communities

Hurricanes create a range of short- and long-term health and economic woes, with vulnerable populations often shouldering the greatest burden.

Flood damages

Flooding isn’t just the deadliest threat; it also causes tremendous damage to homes, buildings, and infrastructure, whether from storm surges or extreme rains. In fact, flooding was the main cause of damage for many of the costliest hurricanes. The trend toward storms with heavier rainfall has put a strain on the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), which has been in debt since Katrina caused $16.1 billion in flood-related damages in 2005. More than 80 percent of the program’s payouts to cover losses have occurred since 2000, even though it was created in 1968.

Economic loss

Hurricanes are the costliest form of weather disaster, accounting for more than half of the total damages from billion-dollar U.S. weather events since 1980. Through 2021, hurricanes averaged $20 billion each in losses. That figure includes everything from wrecked homes to mangled material assets like cars and boats. It also includes damage to public infrastructure including roads, bridges, and power lines, along with lost wages and income-generating assets such as crops, livestock, and businesses. It does not include flooding damage (an average of $4.7 billion per event), health-related costs, or values related to lost lives.

Climate change is expected to further increase the tab, with potential future losses from hurricanes and other extreme weather events projected to cost $2 trillion by 2100.

A resident surveys the damage to her property after Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico in September 2017.

Alex Wroblewski/Getty

Health toll

Hurricane Maria, which struck Puerto Rico in 2017 and is considered the deadliest hurricane in recent U.S. history (nearly 3,000 fatalities), showed how a storm can overwhelm the local electrical, water, and medical infrastructure and take a long-term toll on human health, including mental health.

As the second-most deadly storm in this century so far, Hurricane Katrina struck the U.S. Southeast in 2005 and claimed more than 1,800 lives. The majority of Katrina’s victims perished from the storm surge, which is the main cause of U.S. fatalities related to a hurricane. Flooding from rainfall is the second-gravest danger; together with drownings, either near shore or out at sea, these water events are responsible for 88 percent of all hurricane-related deaths. While a storm’s strength is based largely on wind speed, deaths from falling debris and other wind-borne hazards—including tornadoes spawned by the hurricane—account for only about 11 percent of fatalities.

These statistics don’t tell the full story of how a hurricane impacts health, however. Flood-induced sewage overflows from wastewater treatment plants can dump fecal bacteria into floodwaters and waterways, increasing the risk of skin, eye, ear, and gastrointestinal infections. Runoff from toxic waste sites and factory farms can expose nearby residents to hazardous waste. After the storm has passed, water-damaged homes can harbor bacteria and mold, making the air unhealthy to breathe. Mold can be a particularly pervasive health hazard, since it starts growing immediately and can be hard to detect and remove.

Who are the most vulnerable?

While hurricanes impact everyone living in a storm-affected area, those impacts aren’t shared equally. Low-income communities, people of color, and the elderly are disproportionately exposed to storms. These populations often live in suboptimal housing that’s situated in areas particularly vulnerable to storm threats—sometimes close to polluting industries that raise the risk of contamination via pipeline or facility leaks or chemically contaminated floodwaters. Due to limited mobility, lack of funds, or insufficient storm-warning information, these communities often face greater challenges in escaping impending storms as well. Often, they are unable to bounce back as quickly after a hurricane has passed, facing challenges in accessing public disaster relief, job assistance, and affordable housing.

How hurricanes impact the environment

Ravaged homes and submerged streets are the images most often seen on the news after a hurricane strikes, but coastal ecosystems—both on land and at sea—experience their own forms of devastation as well.

Saltwater/freshwater intrusion

When seawater surges into wetlands, bays, and estuaries, the onslaught of salt can harm freshwater marsh grasses and plants as well as crabs, minnows, and other marine life. When saltwater washes over land, it can harm or even kill bottomland forests and coastal trees unaccustomed to the uptick in salinity. The opposite can happen as well: Heavy rains can cause freshwater to flood into coastal basins, decreasing the salinity of typically brackish waters and imperiling the species that depend on them.

Dislocation of species

Both strong winds and the relative calm of a hurricane’s eye (which acts as a natural cage) can push birds, particularly seabirds and water fowl, hundreds of miles from home. Meanwhile, floodwaters—from both storm surge and overflowing rivers and streams—can strand animals far from their natural territory.

Forest destruction

Hurricane-force winds can uproot trees and bushes or strip them of their leaves, seeds, fruit, berries, and branches, damaging entire wooded ecosystems. This can not only create short-term food shortages for species but also change the face of an entire area. Once a forest canopy is damaged, a once shady, cool, and damp area may become a sun-filled, hot, and dry space—effectively creating new habitat for invasive species while destroying ideal conditions for other, longer-term inhabitants.

Wetland, dune, and beach loss

Storm surges, waves, and winds can destroy wetlands and erode dunes and beaches, which provide critical habitat and important nesting grounds for a wide variety of wildlife species. These areas also provide a first line of defense from storm surge for us humans as well. Wetlands alone prevented an estimated $625 million in flood damage to East Coast communities during Hurricane Sandy. And another study estimated that if Florida had retained just 3 percent of its wetlands acreage, it would’ve saved about $430 million in damage when Hurricane Irma hit in 2017.

Turbid waters

Heavy rainfall and flooding can wash everything from soil and sediment to nutrient pollution and hazardous waste from wastewater treatment plants, refineries, and Superfund sites into marine, coastal, and freshwater environments. The introduction of mud and debris can smother marine life, such as oysters, and damage grasses and agriculture; nutrient pollution can contribute to coral bleaching; and poisonous contaminants can accumulate in fish and shellfish (and then be eaten by us).

What causes a hurricane?

Whether you call them hurricanes, typhoons, or cyclones, these systems result from the interplay of four main ingredients: warm ocean water, cooperative wind patterns, stormy weather, and a dose of bad luck (since the first three ingredients alone aren’t always enough).

How do hurricanes form?

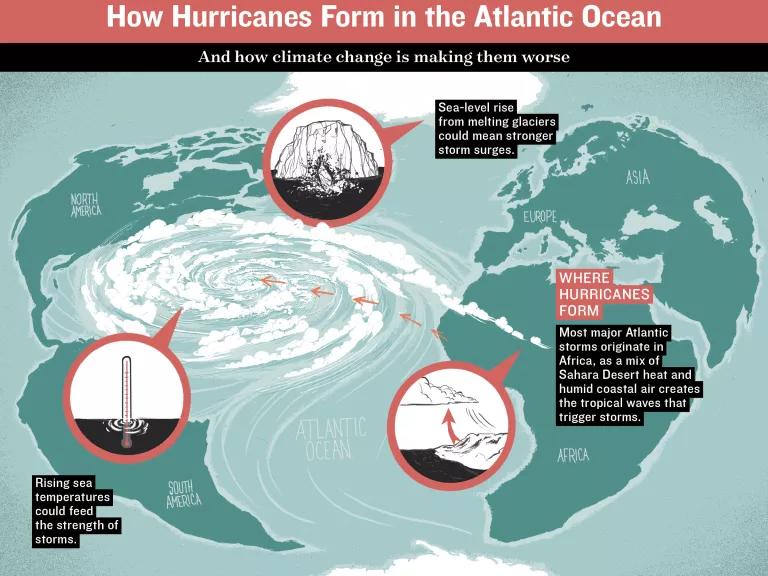

While any tropical disturbance can spawn a hurricane, the origins of nearly 83 percent of major Atlantic hurricanes (category 3 and up) come from North Africa, where the Sahara’s scorching summer heat meets the cooler, more humid air that rises from West Africa’s forested coastal regions. The contrast in temperatures forms an area of strong high-altitude winds known as the African easterly jet, which moves from east to west. Because of the temperature differences in the lands over which it crosses, the jet stream wobbles from north to south, creating atmospheric troughs—basically V-shaped tropical waves—of low-pressure areas that get pushed along by the winds. These tropical waves, which can trigger clusters of thunderstorms, emerge near the Cape Verde Islands, just west of Africa (hence the term Cape Verde hurricane) and continue westward across the Atlantic Ocean.

Aaron McConomy

About 60 tropical waves typically track across the Atlantic Ocean each year, peaking in summer and early fall—around the same time that the ocean is at its warmest. And that’s the kicker: When seawater with a temperature of at least 80 degrees Fahrenheit and a depth of about 165 feet meets a low-level weather disturbance like a tropical wave, conditions grow favorable for hurricane development. As a storm system moves across tropical ocean waters, the evaporation of warm water pushes more moist air up into the clouds, creating a low-pressure pocket near the sea’s surface and fueling the storm. Like water funneling down a drain (but inverted), moist air from surrounding areas rushes in to fill the atmospheric void, then evaporates as well, further fueling the formation of clouds and thunderstorms. As winds pick up and the energy-generating process continues, what was once a tropical disturbance can develop into a tropical depression and then a full-blown hurricane.

Hurricanes and climate change

As we continue to heat the planet by burning fossil fuels, we’re altering both the earth’s longer-term climate systems and its shorter-term weather, increasing the threat and cost of extreme weather events. Here’s a look at how the consequences of climate change—and global warming, in particular—affect hurricanes.

How does climate change affect hurricanes?

Warmer ocean temperatures

Over the past 50-plus years, the earth’s oceans have absorbed more than 90 percent of the extra heat generated by man-made global warming, becoming warmer as a result. Since warm sea surface temperatures fuel hurricanes, a greater temperature increase means more energy, and that allows these storms to pack a bigger punch. Indeed, some weather analysts suggest a link between the intensity of Hurricane Florence—a Cape Verde storm that drowned the Carolinas with record-breaking rains—and warmer-than-normal Atlantic waters.

Rising air temperatures

The burning of fossil fuels and other human activities have caused an estimated 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) of global warming since preindustrial times. Since a hotter atmosphere can hold—and then dump—more water vapor, a continued rise in air temperature is expected to result in storms that are up to 15 percent wetter for every 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit of warming, meaning an even greater capacity to generate flooding.

Sea level rise

As the ocean warms and expands and as terrestrial glaciers and ice sheets melt, sea levels are expected to continue to rise. That increases the threat of storm surge—when powerful winds drive a wall of ocean water onto land—for coastal areas and low-lying nations. Hurricane Katrina’s 28-foot storm surge overwhelmed the levees around New Orleans in 2005, unleashing a devastating flood across much of the city.

Longer-lasting storms

Research suggests that global warming is weakening the atmospheric currents that keep weather systems like hurricanes moving, resulting in storms that linger longer. Sluggish storms can prove disastrous—even without catastrophic winds—since they can heap tremendous amounts of rain on a region over a longer period of time. The stalling of Hurricane Harvey over Texas in 2017 as well as the slow pace of Hurricane Florence helped make them the storms with the greatest amount of rainfall in 70 years.

Have hurricanes increased in number?

While there may seem to be a growing number of hurricanes snatching headlines each year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) does not see a general global trend toward increasing hurricane frequency over the past century. The exception is the North Atlantic, which the United Nations body notes has experienced an increase in both the frequency and intensity of its hurricanes. This is supported by the latest study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The IPCC projects that while there might be a slight decrease in hurricane frequency globally through 2100, the storms that do make landfall are more likely to be intense—category 4 or 5—with more rain and wind.

Are hurricanes getting more intense?

We may not be experiencing more storms, but we are riding out stronger ones, with heavier rainfall and more powerful winds (hence, all those news headlines). Recent research, for example, estimates that Hurricane Harvey dumped as much as 38 percent more rain than it would have without climate change. Another Harvey analysis indicates that the likelihood of a storm of its size evolved from happening once per century at the end of the 20th century to once every 16 years by 2017—again, due to climate change. Looking forward, the intensity of hurricanes that make landfall is expected to increase through the end of this century, with more category 4 and 5 storms.

Hurricane prevention

As the evidence makes clear, the force, strength, and impact of today’s natural disasters is inextricably tied to society’s past choices. Our centuries-long reliance on dirty fossil fuels has driven the global warming trend, and we’re now experiencing the repercussions in the form of more severe weather events, including catastrophic hurricanes.

Of course, hurricanes are natural phenomena, and there is nothing we can do to halt any single storm in its path (though some people may try). We can, however, forgo the burning of carbon-emitting oil, coal, and gas for more efficient renewable energy options—such as wind and solar—and thereby reduce future warming and the ferocity of tomorrow’s storms.

And that’s a big point of the Paris Agreement, which was signed by nearly every nation on earth in 2015 and aims to curb the consequences of climate change by limiting global warming since preindustrial times to, ideally, 1.5 degrees Celsius. But getting there will require serious heavy lifting in the form of immediate, transformative global action, as the IPCC noted recently in its stark report drafted by some 270 climate scientists representing 67 countries. It will mean slashing global carbon emissions by nearly half by 2030, relative to 2010 levels, zeroing out emissions entirely by about 2050, and meeting as much as 87 percent of global energy needs with renewable sources. The alternative, as laid out by the IPCC, is clear: With a business-as-usual approach, the “extreme” weather of today will seem commonplace by tomorrow.

Think globally, act locally

Unfortunately, members of Congress have chosen to ignore the overwhelming evidence from climate scientists worldwide that demands we take sweeping action to stop the use of fossil fuels. Instead, they’ve made every effort to delay meaningful climate action, doubling down on policies that continue to promote fossil fuels.

Fortunately, many American leaders—and much of the rest of the world—are pushing ahead. Mayors, governors, companies, and utilities are all charting their own course and finding new ways to tackle climate change. And President Biden has committed to taking executive actions that will make communities more resilient and protect public health.

That’s where individuals come in, too—especially everyday Americans, who on average produce nearly four times more carbon pollution than citizens elsewhere. As customers, we can support companies invested in meaningful climate action. As U.S. citizens, we can urge political leaders to prioritize clean energy and energy efficiency. And as global citizens, we can take myriad steps to slash carbon pollution from our own daily lives. As the IPCC report shows, there’s still enormous work to be done, but it is only the ramping up of these efforts that will move the needle on climate change.

Reduce damage and loss

While we may not be able to prevent the next hurricane, there are ways to reduce the widespread destruction these storms leave in their wake. First, communities, cities, and states should work together to improve climate resiliency and ensure that public safety is a primary factor in determining where and what we build.

A critical component of this effort would be an overhaul of the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), the federal flood insurance program that covers more than five million property holders. Currently, it incentivizes the rebuilding of properties in flood-prone areas rather than helping victims move out of harm’s way. More than 30,000 U.S. properties have been flooded an average of five times each (with some homes flooded 30-plus times) and then reconstructed with the aid of NFIP. With some commonsense reforms, such as helping homeowners relocate, updating flood maps to reflect new climate realities (including sea level rise and its effects on local storm surge levels), and sharing data on flood hazards, the program could better keep America safe and dry.

Another way to build hurricane resiliency is the newly reinstated federal flood protection standard from 2015, designed to keep communities safe and reduce damages from natural disasters. The program ensures that any new, federally funded infrastructure projects, such as schools, hospitals, public housing, and police stations, will be built outside flood-prone areas or at least made more resistant to flooding.

Measures such as these could result in major cost savings. Indeed, according to a report by the National Institute of Building Sciences, every $1 spent by the federal government on hazard mitigation today—for example, reducing the number of homes in flood-prone areas and increasing the weather resilience of buildings—could save $6 in future disaster-related expenses. And adopting the most current building code requirements will save even more: an estimated $11 per $1 invested.

How to prepare for a hurricane

If you live in an area considered at risk for hurricanes, knowing what to do before, during, and after a storm will go a long way toward keeping you safe. Below are a handful of hurricane safety tips.

Aaron McConomy

Hurricane preparedness list

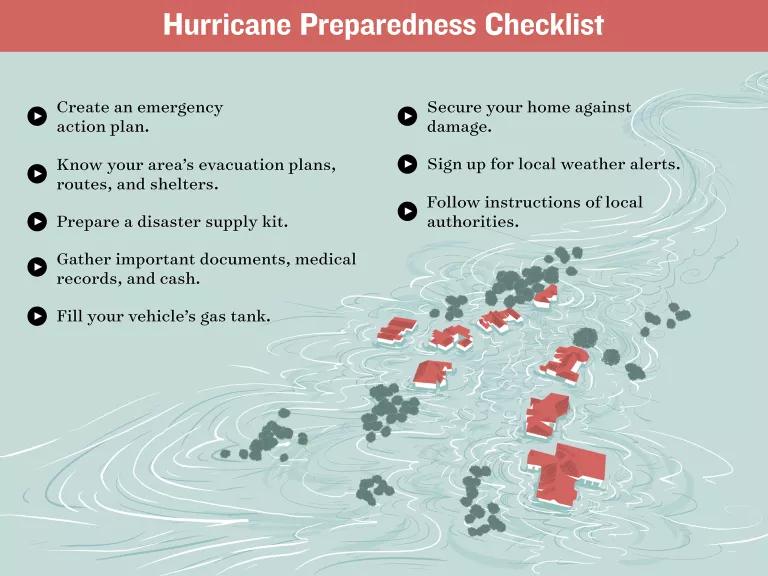

- Put an emergency action plan in place to ensure that you and your family know what to do, where to go, and whom to contact in case of a hurricane.

- Visit your local government website to find out if you live in a hurricane evacuation area and to familiarize yourself with your area’s evacuation plans, routes, and shelters.

- Prepare a disaster supply kit with enough water and food to sustain your family and pets for three days, plus basic household items such as power sources and a first aid kit.

- Before a storm hits, add last-minute essentials such as medications, important documents and medical records, and cash, which can prove essential if the power goes out.

- If a storm is possible, fill the gas tank of your vehicle and/or generator in advance.

- Review your homeowner’s insurance policy and consider insuring your property against the extreme weather events you may face in your area.

- At the start of hurricane season, inspect your home for vulnerabilities. Fix loose shingles, clear drains and gutters, and remove tree branches that could pose a threat during high winds and heavy rain.

- To avoid flood damage, consider home improvements such as elevating boilers and central air-conditioning units, installing a sewer backflow valve, and landscaping to guide water away from your house.

- Before a hurricane’s arrival, secure your property by protecting windows with hurricane shutters or plywood and removing outdoor furniture, trash cans, and other items that could blow away.

- Sign up or download apps for local weather alerts to stay on top of storm developments. And keep in mind this key terminology: A “hurricane watch” indicates a storm may happen within 48 hours, while a “hurricane warning” means a storm is expected within 36 hours.

What to do during a hurricane

Before, during, and after a storm, follow the instructions of local authorities. If told to evacuate, do so immediately. As a storm develops, evacuation routes may close.

If forced to weather a storm in place, stay away from windows, skylights, and glass doors, which can shatter. Head to an interior room, bathroom, or closet. If floodwaters are a threat, head to the highest floor—excluding closed attics, where you could become trapped if floodwaters rise high enough. Do not operate gasoline-powered machinery, such as generators, indoors as that can cause monoxide poisoning.

Remain inside until officials give the all clear on a local website, radio, or television station. If you do venture outside, avoid floodwaters, which may contain dangerous debris or hide downed power lines. And remember: Six inches of fast-moving water can sweep you off your feet, and just one foot of moving water can wash a vehicle away. Finally, if you're feeling emotional distress, don't hesitate to reach out for help.

This story was originally published on December 3, 2018, and has been updated with new information and links.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

What Are the Solutions to Climate Change?

Climate Tipping Points Are Closer Than Once Thought

What Are the Effects of Climate Change?