Environmental Injustices Plague Parchman Prison, Mississippi

For years, the people incarcerated at the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman have reported a host of problems relating to drinking water and sewage. Now, an investigation confirms repeated and likely ongoing environmental violations at the notorious Parchman prison.

The main entrance to the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman

Mississippi Department of Corrections

An investigation by NRDC and our partners at the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) reveals persistent and continuing drinking water and wastewater violations at the notorious Parchman prison in Mississippi.

Individuals incarcerated at Parchman have long reported discolored drinking water tasting alternately of sewage and strong disinfectant, as well as inoperable, overflowing toilets and many other water issues. NRDC and SPLC investigated these complaints—and found widespread malfunctioning and ill-maintained drinking water and sewage treatment systems. In a joint letter sent to prison officials, Mississippi state agencies, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, NRDC and SPLC describe Parchman’s multiple, years-long violations of federal environmental laws and urge the agencies to diligently resolve them to protect the health of individuals incarcerated there.

Parchman Prison: An Infamously Violent Institution

Mississippi State Penitentiary, known as Parchman Prison or simply “Parchman,” has a notorious history that extends well beyond its present-day environmental problems. Located in rural Sunflower County in the Mississippi Delta, about 100 miles south of Memphis, Parchman has long been known for violence, inhumane conditions of confinement, and exploitation of inmates.

Built in 1904 and designed to mirror the plantation slavery system, Parchman quickly became a source of free labor for the state of Mississippi. While the 13th Amendment abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, it includes a loophole: “except as punishment for crime.” Southern states capitalized on this exception, adopting criminal statutes known as “Black Codes.” Under those laws, Black Southerners were targeted for behavior that had been criminalized, including unemployment or “vagrancy,” and given lengthy sentences. Once arrested and incarcerated, they were leased by the state to private companies for manual labor on plantations, railroads, and factories in a practice known as “convict leasing.” Parchman engaged for decades in convict leasing and became known for its brutal labor conditions and culture of violence towards incarcerated individuals, who were frequently tortured or whipped as punishment and made to live in derelict conditions.

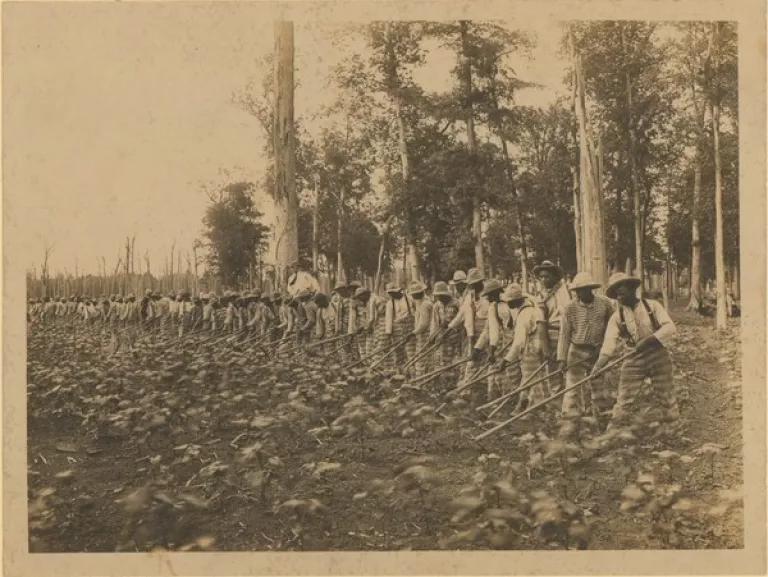

Men incarcerated at Parchman hoeing in a field in the early 20th century

Today, the prison extends over 18,000 acres, with seven housing units and around 2,000 inmates. Decades of hard-fought attempts to reform the prison’s inhumane conditions have achieved some important changes. But after more than a century operating as a prison, in many ways, Parchman’s deplorable legacy remains a reality for the people incarcerated there. Every day individuals incarcerated at Parchman contend with crumbling infrastructure, understaffing, a lack of light and electricity, inoperable and rarely cleaned toilets, frequent flooding and leaks, exposed live electrical wires, black mold, and vermin infestations. Violence continues to be prevalent at Parchman, while COVID-19 poses particularly deadly risks to incarcerated people across the country. Since the beginning of 2020, more than 50 people have died while in Mississippi Department of Corrections (MDOC) custody at Parchman. Parchman today remains a major symbol of the failures of mass incarceration policies in the United States.

Environmental Health Issues Abound at Parchman

In an investigation of the malfunctioning sewage treatment system and drinking water problems at Parchman, NRDC and SPLC found systemic failures and multiple violations of federal environmental laws. The following sections outline our findings and recommendations for Mississippi state agencies to remedy these egregious and dangerous violations.

Inadequate Wastewater Treatment

The Clean Water Act, a bedrock federal environmental law, regulates the discharge of wastewater into rivers and waterbodies to protect public health and the health of the nation’s waters. Our investigation found that Parchman has exceeded for years and continues to exceed the contamination limits in its Clean Water Act permit governing the prison’s discharges of wastewater into surrounding waterways . The resulting polluted discharges may endanger the health of people who live along, fish in, and otherwise use those waters. Moreover, Parchman’s sporadic and unreliable monitoring means that the true extent and impact of the prison’s polluted wastewater is unknown.

Our investigation also found that Parchman’s wastewater system is both in disrepair and mismanaged. Despite years of violation notices, Parchman has continuously failed to properly operate, maintain, and repair its system. Malfunctioning equipment caused Parchman to have to “bypass” the sewage treatment process entirely and discharge raw sewage into surrounding waterways. Parchman’s neglect of its system and inadequate reporting make the current wastewater violations unsurprising, and future violations likely. Indeed, prison officials have conceded that the current treatment system is simply incapable of removing enough contamination to meet the limits in the prison’s permit.

Mississippi state agencies must implement a plan to properly maintain and operate Parchman’s wastewater system. This includes evaluating whether treatment upgrades are needed to keep the system operational and effective, making public Parchman’s full monitoring and violations data, and making all necessary changes to limit the amount of contaminants being discharged into nearby waterways and comply with Parchman’s Clean Water Act permit.

Hitchin’ Hill, where many locals go to fish and recreate, about 8 miles from Parchman

Drinking Water Quality Problems

Over the past several years, people incarcerated at Parchman have consistently reported concerns about the drinking water in the prison, noting that it is often discolored and has a foul smell and taste of sewage or disinfectant. Many have expressed concerns that the poor quality of the drinking water is linked to health conditions they have experienced while incarcerated at Parchman, like constipation, nausea, and skin problems. Many mix in coffee or other powders to make the water drinkable, and others choose to avoid the tap water altogether. Those who have the means often purchase bottled water from the canteen. Staff also refuse to drink the water.

The Safe Drinking Water Act is another essential federal environmental law that protects the quality and safety of tap water in public water systems nationwide. Our investigation found that Parchman has violated and may be continuing to violate this law in several ways.

First, despite a requirement that the prison automate the controls on its groundwater wells, for years Parchman has operated its wells manually. Automatic controls allow a system to more effectively disinfect water and detect other treatment problems. Parchman’s manual system has caused inconsistent disinfection and is prone to human error and neglect. The failure to install automatic controls in a timely manner may have contributed to unsanitary drinking water in the prison. Troublingly, it has taken years for MDOC to address the issue. In NRDC and SPLC’s letter, we urge the Mississippi State Department of Health to confirm that Parchman has upgraded its drinking water wells to include automatic controls and ensure that the water is properly treated and safe to drink.

Additionally, MDOC has not adequately monitored the chemicals used to disinfect drinking water, such as chlorine. The Safe Drinking Water Act requires water systems like Parchman’s to sample chlorine every day at the peak times of water use to ensure disinfection remains at a safe level. But our investigation revealed that Parchman has regularly failed to complete daily sampling, and sometimes even failed to sample for several consecutive days. Monitoring is critical to ensure that water is safe to drink, and Parchman is at least intermittently violating its monitoring requirements. Our letter recommends that MDOC not only conduct required routine monitoring of chlorine levels in the drinking water, but also publicly report any violations. We also recommend that MDOC and the Department of Health conduct a full investigation into what is causing the poor color, odor, and taste irregularities in Parchman’s drinking water and any associated health threats.

Prisons and Environmental Justice

Across the country, many rural communities, low-income communities, and communities of color disproportionately lack access to essential public services and experience environmental burdens similar to the wastewater treatment and drinking water quality issues rampant at Parchman. These environmental injustices expose these communities disproportionately to contamination and serious health risks. Meanwhile, racial disparities persist in policing, arrests, sentencing, and incarceration throughout the United States. Incarcerated people across the country exist at the nexus of these environmental health crises and a criminal punishment system rooted in racism. The connection between mass incarceration and environmental injustice is clear.

Parchman’s violations of federal environmental laws underscore nationwide problems beyond the crumbling infrastructure of this one prison. It is essential that Mississippi’s Departments of Corrections, Health, and Environmental Quality act immediately to remediate the environmental problems plaguing the prison and improve conditions for Parchman’s inmates and the surrounding communities.