Alton Coal Lawsuit: Saving America’s Best Idea from the World’s Worst Idea

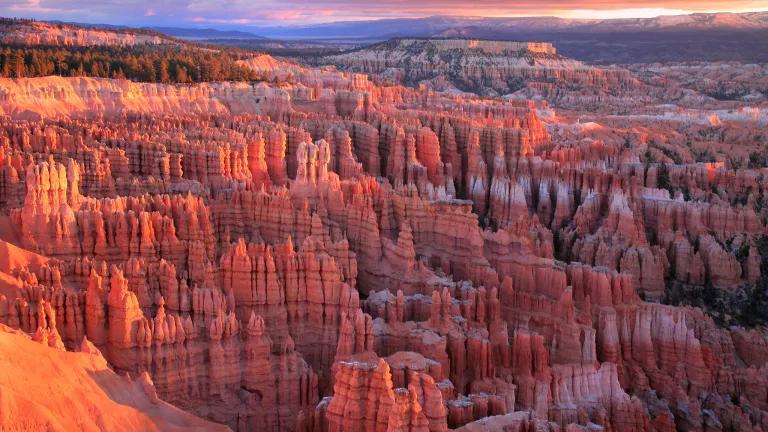

A Utah federal District Court has opened the door for the Biden administration to finally halt the Alton Coal Mine expansion—following a decade-long legal fight to protect public lands near Bryce Canyon National Park.

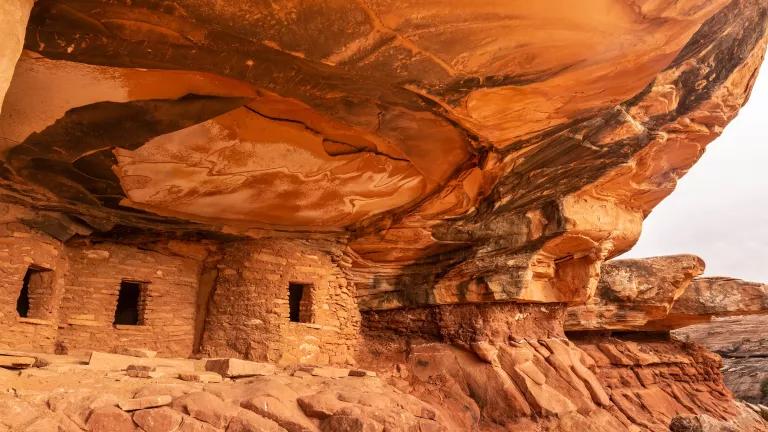

NPS

UPDATE: On March 25, 2021, a Utah federal District Court opened the door for the Biden administration to finally halt the Alton Coal Mine expansion—following a decade-long legal fight to protect public lands near Bryce Canyon National Park. The court brought down the hammer over what should have been obvious to BLM from the get-go -- you can’t trumpet this mine’s supposed economic benefits without also talking about its colossal climate costs. We hope the Biden administration takes this opportunity for a fresh look at this truly awful project.

In the competition for the world’s worst idea ever—an arena that includes Prohibition, Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, trading Babe Ruth to the Yankees, and Jar Jar Binks—the federal government’s approval of a gigantic open pit strip mine on the doorstep of Bryce Canyon National Park is a contender. And as with virtually all of the terrible environmental ideas to emanate from the current White House, NRDC is fighting it.

Today, NRDC and our allies filed a lawsuit in federal court challenging the decision by the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to allow the mine to move forward on our federal lands.

The 2,114 acres slated for strip mining by Alton Coal Development are located just off Utah’s Route 89, a scenic two-lane byway connecting Bryce Canyon and Zion, two of the most visited national parks. As we have detailed in earlier posts and expressed in our comments to BLM, there are a host of entirely predictable problems with putting a large-scale industrial operation so close to one of America’s most treasured national parks.

- The mine is expected to increase traffic of huge coal-hauling trucks by 33 percent on the portion of Route 89 closest to Bryce Canyon.

- Mining operations will degrade the park’s beautiful dark night skies—a big draw for tourists, who flock to Bryce Canyon’s active astronomy and night sky programs—with industrial lighting and airborne dust.

- The operations will increase noise levels in the surrounding area.

- The mine could very well eliminate the southernmost population of the greater sage grouse, a species increasingly at risk from extractive industry in the West, by wiping out the breeding ground that the population relies on.

- Air pollution would increase, impacting park visitors.

The list goes on—all this for an operation that is fundamentally unnecessary, as coal markets continue to atrophy in the United States and abroad in the face of the increasing economic viability of renewable energy.

For purposes of our lawsuit, though, we have homed in on a particular legal problem with BLM’s approval of the coal lease to Alton: the agency’s failure to think through the environmental consequences of burning the two million tons per year of coal anticipated to be extracted from the mine.

As part of the approval process for the lease, BLM was required under the National Environmental Policy Act to prepare and issue an environmental impact statement (EIS) to ensure that both the agency and the public are fully informed of the mine’s likely consequences. The final EIS issued by BLM goes on at considerable length about the supposed financial benefits of the project: the economic value of the coal, the federal royalties, tax revenues, and the like. However, it does not say one word quantifying the economic hit the world will take from the anticipated 4.8 million tons per year of greenhouse gas carbon dioxide that will be emitted when all that coal is burned.

There are readily available tools for estimating the monetary cost to the world of climate pollution, such as the Social Cost of Carbon, a formula developed by the former federal Interagency Working Group, which takes into account all manner of damage to our communities and ecosystems that results from climate change, such as diminished agricultural productivity, droughts, wildfires, increased intensity and duration of storms, ocean acidification, and sea level rise. But BLM did not use any of these tools, resorting instead to hand-waving generalities about climate change that contrast sharply with the specificity of its pro-coal economic accounting.

The EIS additionally failed to account for all the other types of pollution that will result from burning two million tons of coal a year, with BLM claiming it didn’t know where exactly the coal would be burned—even though elsewhere in the document, the agency specifically assumed it would all be burned at Utah’s Intermountain Power Plant.

The battle over this mine has been long, and in a sensible world, it would not have ended in litigation. Following on the heels of two rounds of EIS drafts, which elicited a massive outpouring of public comments expressing concern with the project, President Obama’s Interior Secretary Sally Jewell in 2016 released an order putting a moratorium on all of BLM’s coal leasing pending completion of a global environmental review of the entire leasing program. A thorough review of this nature ought to have revealed the sheer folly of the proposed Alton mine. The leasing moratorium and coal program review, however, were unceremoniously kicked to the curb by the Trump administration, which rescinded the moratorium in early 2017.

So here we are, fighting in court to protect America’s best idea from the world’s worst idea. We are asking the court to vacate the deficient EIS and send it back to BLM with an order to do the environmental analysis required by law. Mining the federal coal has not yet begun, as Alton still needs additional permits before it can begin work. So there is still time for reason to prevail—and NRDC will continue to do everything possible to help ensure that it does.