California’s Orphan Well Problem Needs More Than Money

If money were the answer to every problem, then by all accounts solving California’s idle and orphan oil well problem ought to be going swimmingly.

A rusty pumpjack at an abandoned oil well in the southern San Joaquin Valley, Maricopa County, California.

California is expecting to receive well north of $100 million in federal funding for remediation of orphan wells. And the 2022-23 state budget for the Natural Resources Agency allocates $50 million for that purpose, with another $50 million slated to be appropriated in the next budget cycle.

It’s a ton of money – even if not nearly enough to cover the likely cost to the state of cleaning up orphan wells (meaning idled wells with no identifiable party on the hook to pay), which has been estimated at half a billion dollars. But in this case, as in pretty much any bureaucratic enterprise, money is necessary but not sufficient. The money will only help pull us out of our current mess if we have enough people to manage it, a strategy to spend it effectively, and a plan to limit future expenditures so that the problem does not become a taxpayer-funded black hole.

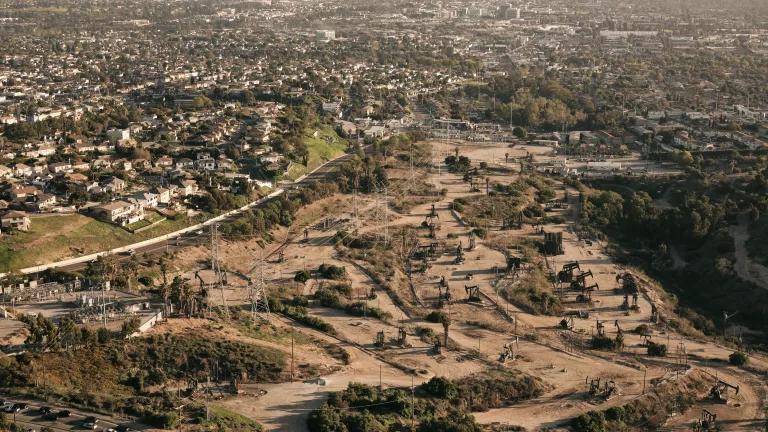

And to be clear, it’s quite a mess. California’s oil industry is slowly dying, and leaving environmental wreckage behind. Huge numbers of wells in the state – estimated at around 70,000 - are either completely idle or else marginal, meaning they’re only producing a trickle and on their way out. Although drillers are supposed to be cleaning up their idle wells – a process called “plugging and abandonment” - that’s not exactly what’s happening. Already about 5,000 idle wells are likely orphaned – with the state holding the bag for cleanup costs. And the 70,000 are at risk of that happening, as they get transferred to smaller and less financially robust owners. And it’s not just a long-term problem: these idle wells are leaking dangerous amounts of methane and toxic air contaminants right now, with no one effectively minding the store (more on that in a moment).

The Newsom administration and legislature have taken a few positive first steps toward making sure the newly appropriated funds are well spent. The Resources Agency budget includes funding for five new positions, including two oil and gas engineers and a geologist. And the California Geologic Energy Management Division (CalGEM) has finally issued in draft its proposal for how to decide which wells to prioritize for cleanup (the proposal needs a fair bit of work still, for reasons described in our comments on it).

But these steps are the tip of the iceberg of what needs to be done to address the slow-moving catastrophe of California’s idle and orphan wells. Significant effort is going to be needed at all levels of government – the Governor’s office, multiple administrative agencies, and the legislature – to ensure that the orphan well funding pouring into CalGEM is spent effectively, and that the public is protected from the dangers these wells pose before they are plugged and abandoned.

There are three basic types of steps that need to be taken to use our newfound resources effectively and get us on the right path, all documented in a recent letter sent to Governor Newsom by NRDC and more than 100 environmental and community-based organizations. First, we need to stop the pollution leaks, and more fully monitor and regulate them. Second, CalGEM needs to more fully use its existing authority get idle wells plugged and abandoned while there is still an operator on the hook to pay for that process; and to increase financial assurance requirements when issuing new permits. And third, the legislature needs to step in to fix inadequacies in CalGEM’s governing statute that helped land us where we are today.

1. Fix the Leaks

We don’t actually know how bad the leaking idle well problem is, precisely because no one has been minding the store. The investigative reporter at the Desert Sun on the oil wells beat, Janet Wilson, has documented not only several dozen idle wells spewing methane – some of them at explosive levels near schools and people’s homes – but also the staggering failure of CalGEM to do anything about it. Wilson’s source inside CalGEM disclosed that regulators were tracking the wells through “remote witnessing,” meaning they were checking on the situation from the comfort of their desks, relying on photos sent by the oil companies – since, as one anonymous staffer put it, “Who wants to be outside on a 100-degree day in Bakersfield looking at oil wells?” CalGEM employees had also been directed to prioritize inspecting wells in low-risk areas away from homes because they are more thickly clustered there and it’s easy to cover more of them – calling to mind the old joke about the drunk guy who’s looking for his lost keys under the streetlight even though he didn’t lose them there, since it’s easier to see.

We now we have further evidence of the magnitude of the leaking well problem from FracTracker, a group of technical specialists who gather data on the oil industry. Their recent report inspected around 100 drill sites, and resulted in the filing of 68 air quality complaints to local air districts. The wells FracTracker inspected are a tiny fraction of the state’s total, but are consistent with other researchers’ estimates of the percent of idle wells that are leaking, which some have put at 65 percent (a number that FracTracker thinks could be “much higher”)

And add a transparency problem to the mix. One of the concerning findings in the report was that many of the wells FracTracker looked at appeared to have been repaired very recently – but the problems requiring repair had not been reported either to the California Office of Emergency Services nor on CalGEM’s website. CalGEM admitted to FracTracker that it did not maintain a list of remediated wells even when CalGEM funds had paid for the remediation. As pointed out in the letter to the governor, CalGEM has additionally failed to comply with statutory requirements to submit reports on idle wells. And contributing to this cloak of invisibility is the California Air Resources Board (CARB), which is not tracking leaks of methane – a greenhouse gas more than 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide as a driver of climate change – for the state’s greenhouse gas inventory, potentially calling into question California’s ability to meet its ambitious goal to achieve carbon neutrality by 2045.

CalGEM has taken a few modest steps to deal with the problem. It put a page up describing steps taken to remediate the recently identified leaking wells; and another where citizens can report leaks. And at Governor Newsom’s request, CARB and CalGEM have initiated a Methane Task Force, although it’s still a bit unclear following the initial meeting exactly what it will accomplish.

As described in the letter to the governor, while we’re not opposed to meetings and web pages, much more than that is needed – including and especially fixing the regulatory loopholes that allowed the situation to spiral out of control the way it has. These were our recommendations:

- Eliminate the heavy crude loophole. The San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District has a rule requiring leak detection and repair (LDAR) for oil wells – but none of the recently-discovered leaking wells in Bakersfield were covered by the rule, which exempts wells producing heavy crude oil (below 20 API gravity and not steam-enhanced, to get technical). The US Environmental Protection Agency recently found invalid a similar exception applicable too active operations. There is no good reason for the exemption – CalGEM and CARB should both work with the Air District to eliminate it.

- Eliminate the small leak loophole. The rules also exempt leaks that occur at a rate of less than 1,000 parts per million (ppm). This allows inspectors to measure using a simple detection device; but the effect is to give a pass to leaks that risk chronic exposure to frontline communities. Looking only at concentration does not take into account the volume or duration of the leak, both of which affect the degree of harm to the local population.

- Define an action level for remediating methane leaks. Methane is a threat to public health and safety not only because it’s a potent greenhouse gas, but also because it can immediately harm people in high concentrations (like those coming out of some of the Bakersfield wells) through explosion or asphyxiation. The California Department of Toxic Substances (DTSC) defines a “methane hazard” with reference to a concentration level accumulated beneath the footprint of a school building. CalGEM can and should define a hazard level of that nature for (among other things) oil extraction-related methane concentrations beneath schools, homes, and other places where people live and gather.

- End the practice of “remote witnessing” as an inspection method. It is simply not adequate to rely on photos sent by oil companies as a substitute for an on-site inspection. The practice of remote witnessing needs to end. If that means CalGEM needs to hire more people to conduct inspections, then it should seek an appropriation for that purpose.

- Prioritize leak inspections in populated areas. Just as CalGEM is developing a system to prioritize wells in populated areas and posing particular hazards for remediation, it should develop a parallel system to prioritize for leak inspection the wells that pose the greatest risk.

- Complete the fugitive emissions study. CalGEM was required by statute to complete a study of emissions from idle wells by July 1 of this year, but it has not done so yet. It reported in January that it was using drones to monitor methane emissions, but did not publish any results.

- Consistently report leaks and repair to the public. CalGEM needs to maintain a publicly-available list of all wells it has inspected, indicating where repairs have been made to address identified leaks. The leaks should also be reported to the Office of Emergency Services.

- Enhance opportunities for public reporting of leaks. While it is a positive step that CalGEM has developed a website where citizens can submit reports of observed leaks, not everyone in frontline communities has access to the internet. CalGEM should allow call-ins as well.

2. Step Up Use of Existing Authority to Keep More Wells From Being Orphaned

The money appropriated by the federal government has, entirely appropriately, been slated to address orphan wells, not the wells where there’s a current or former operator still around to pay for the cleanup (the state appropriation, unfortunately, is a little more open-ended). While public money clearly should not be used to pay where there is a private entity on the hook, it’s essential that CalGEM take action to keep more idle wells from becoming orphaned and dependent on the state’s taxpayers for cleanup.

Unfortunately, right now there is an enormous risk of idle wells sliding into the orphan category. Already, many idle wells are owned by small and sometimes sketchy companies whose holdings consist mostly of idle or marginal wells – this was the case for almost all of the wells found to be leaking in Bakersfield. One of the owners of the Bakersfield wells, Sunray Petroleum, is listed by the California Secretary of State as Franchise Tax Board suspended; and by the Nevada Secretary of State with a corporate status of “permanently revoked.” The company filed for bankruptcy in 2011, and has a long history of idle well regulatory violations.

In theory, the CalGEM regulatory system is designed so that taxpayers would never have to pay for well plugging and abandonment, because oil drillers are required to post a cleanup bond up front when receiving a permit. Where this system fell apart is in the amount of bonding required – which has been, to use the technical finance term, piddling. A particular problem is that operators owning multiple wells are allowed to post “blanket bonds” covering all of them, but at entirely insufficient levels (e.g., $200,000 for up to 50 wells, potentially equaling $4,000 per well). As a result, the state is catastrophically under-funded to pay for plugging and abandonment. A recent report estimated that while the average cost to clean up a single well is around $68,000, the average available bond funding available per well is just north of $1,000.

Our letter to Governor Newsom recommends two basic steps that need to be taken to stanch the slow bleed of idle wells into orphanhood:

- Maximally use existing authority to plug idle wells. CalGEM has extensive authority to order operators to plug idle wells, under various circumstances evidencing risk of the well becoming orphaned. CalGEM can order plugging of wells that cities and counties identify as having no reasonable expectation of being reactivated; wells idle for at least 15 years with no engineering analysis showing viability; wells that have been idle for more than 25 years where certain circumstances are met; leaking wells; and wells for which there is an unrebutted presumption of desertion defined by regulation. There may well be thousands of wells that fall into these categories. CalGEM should order them all plugged immediately, before they have to be dealt with on the public’s nickel.

- Maximally use authority to increase bonding amounts. Three years ago, legislation authored by Senator Monique Limon gave CalGEM extensive authority to increase oil well bonding levels based on various defined risk factors. CalGEM appears to not be using that authority yet – it is still working on procedures for its application. It’s essential that CalGEM start deploying its authority immediately to ensure adequate bonding moving forward.

As with the leaking wells problem, CalGEM also needs to step up its public transparency. It needs to complete the statutorily-mandated reports it is late on – including a report that was due to the legislature in April 2021 concerning the estimated cost of plugging and abandonment of orphan wells and a timeline for achieving it. CalGEM should also start posting on its website a list of all wells ordered plugged, and the status of the work.

3. Push for Needed Legislative Fixes

While CalGEM does have the extensive authority described above to start making a dent in the idle well problem, more is needed. We are encouraging the Newsom Administration to support legislation that would clarify and bolster CalGEM’s authority to order idle well plugging and abandonment and collect the needed bond funding. Among other things, we are recommending:

- Enhanced bonding authority. While Senator Limon’s bill three years ago was a huge improvement over the then-status quo, CalGEM needs even stronger authority to effectuate a long-term fix to California’s deficient bonding problem. The bill caps the enhanced bonding authority at $30 million per operator, which is not enough to cover the full cost of remediating all wells held by large operators. In addition, CalGEM should be authorized and required to demand bonding that actually matches estimated plugging and abandonment costs any time a well is transferred to a new operator – to address the common situation where wells are passed off to less solvent operators as production declines, until they end up like the some of the Bakersfield wells: leaking and owned by a functionally insolvent entity.

- Strengthened and clarified CalGEM authority to order cleanup. While CalGEM has a decent amount of authority right now to order idle well cleanups, and should use it, that authority is somewhat all over the map in terms of details and timelines, a result of years of statutory accretions. The current pastiche of requirements needs to be reformulated into a clear and consistent deadline for remediating idle wells, that is mandatory on both CalGEM and operators. That deadline should reflect the actual risk of leakage of harmful pollutants over time.

- Funding for more CalGEM personnel. CalGEM will not be in a position to address the idle and orphan well problem – or effectively spend the hundreds of millions of dollars appropriated for that purpose – without hiring more staff. While it’s a positive first step that this year’s budget includes five new positions, that number strikes us as desultory and inadequate in the face of the current challenge. More funding for new hires is going to be necessary.

And last but absolutely not least, we are encouraging the governor to work with the legislature to come up with a plan to phase out oil drilling in California altogether. Our state has dug itself into a deep hole with a century and a half of authorizing oil drilling with no viable plan to clean up the aftermath. And as they say, the first thing to do when you find yourself in a hole is to stop digging.