Yesterday, I posted this piece about California’s recent experiences with its Delta water supply and the challenges that the ongoing Bay Delta Conservation Plan process still faces to develop a plan to meet state-mandated co-equal goals to provide a “reliable water supply” and “protect, restore and enhance the Delta ecosystem.” I also promised to apply my “simple steps” approach to translate science into plans to solve environmental and resource management problems to the Delta water supply reliability issue. Here goes….

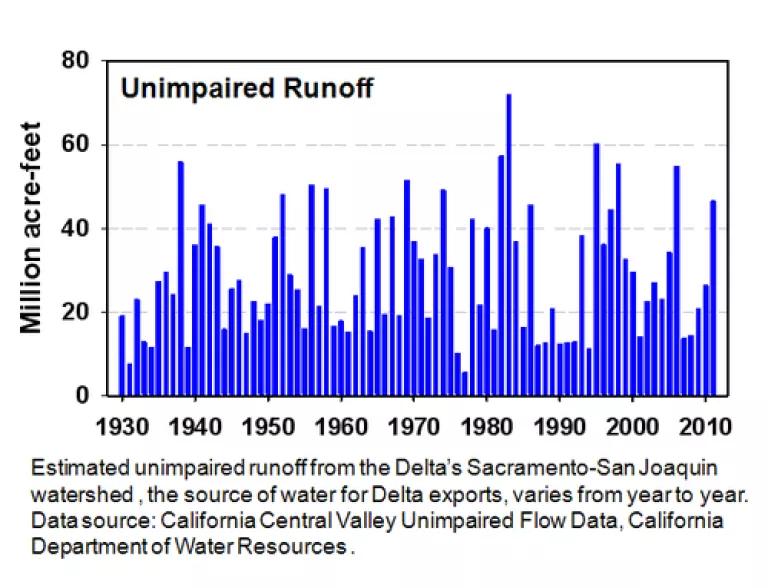

Step 1: What have you got? Accepting the underlying premise that the current Delta water supply is unreliable, existing conditions analysis shows that California has three major challenges relevant to the issue. First, the amount of source water from the rivers and streams that flow to the Delta is finite and variable—we get what Mother Nature gives us and that varies from year to year. Second, there are structural and functional limitations in the system’s plumbing infrastructure. Currently, there are large upstream storage facilities on all of the Delta’s nine largest rivers—and contrary to popular opinion, building new dams or enlarging these existing ones does not create new water, it just allows us to rearrange the timing of when water flows into the Delta. The existing conveyance system, which uses Delta channels to move water to the pumps is old, at risk of catastrophic collapse if Delta island levees fail, and its operations, which reverse natural flows and suck fish (and their food) into the pumps, are harmful to the Delta ecosystem. Finally, demand for water from the Delta and its upstream watershed has already exceeded the capacity of the river, Delta and San Francisco Bay estuary ecosystems to absorb without substantial and possibly irreversible harm to the valuable ecological, water quality, recreational and commercial services they provide. The State Water Resources Control Board, the National Academy of Sciences, and the multidisciplinary team of scientists charged with identifying the causes of recent Delta fish declines and the Environmental Protection Agency have all concluded that current flow conditions are insufficient to sustain (much less restore) the ecosystem and its fisheries. Therefore, in order to meet both co-equal goals, plans to meet the reliable water supply goal are going to have to do it while providing more water for environmental flows.

Step 2: What do you want? In California, the phrase “reliable water supply” is like a Rorschach test: some people see only the word “supply” while others focus on “reliable.” Still others confuse “supply” with “demand,” interpreting the goal to mean meeting current or future water demands, or they relate reliability only to the system’s plumbing rather than the supply of water itself. However, for a plan intended to “provide uninterrupted service” to urban and agricultural water users (the definition articulated by the CALFED Bay-Delta Program nearly ten years ago and since adopted by the Delta Stewardship Council), I would argue that the most effective type of goal would be one that identifies the specific amount of water that can be exported from the Delta on reliable basis, in 95% of years, for example. And since the plan must simultaneously meet the ecosystem goal, this means that the actual numeric water supply goal will need to be derived from analyses to determine the currently unmet ecosystem needs, rather than as a statement of desired export amounts or even current demand.

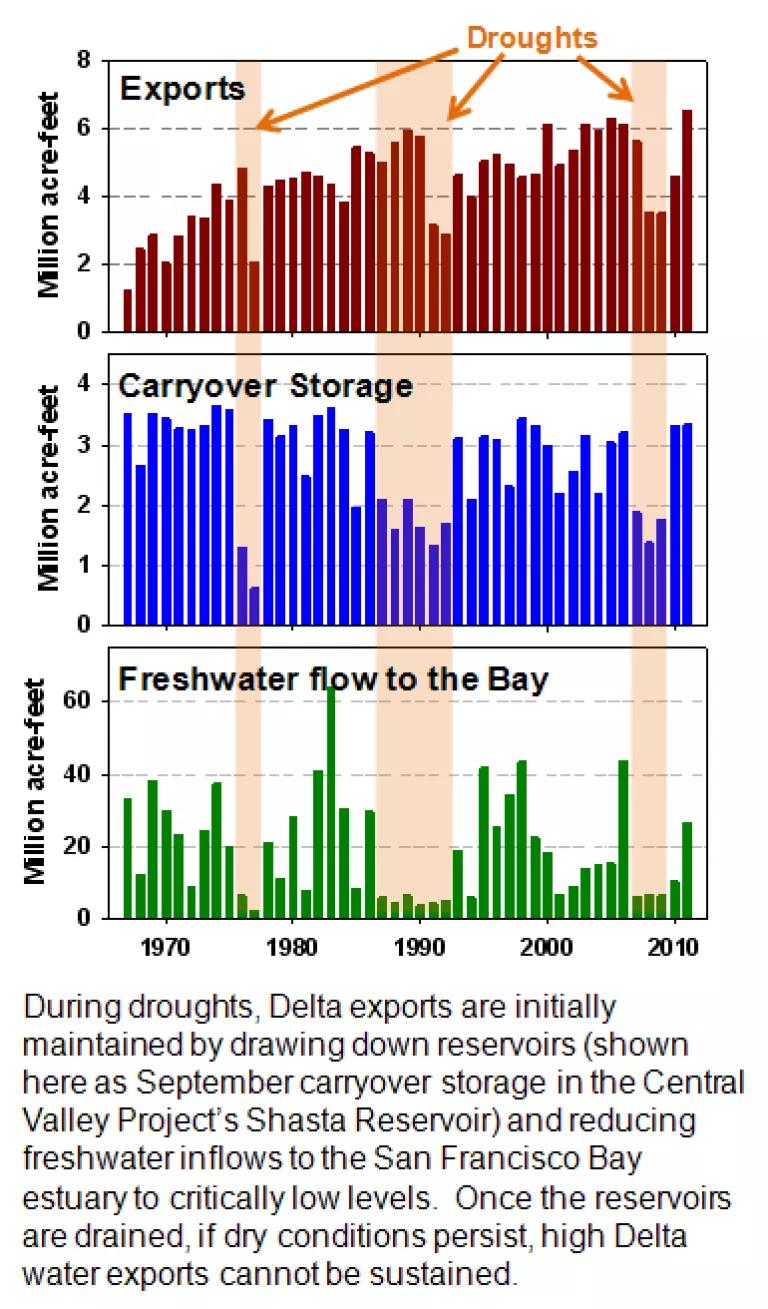

Step 3: What are the causes? The list of factors that affect the ability of the Delta to export water and provide a reliable water supply is not that long. Runoff to the Delta’s tributary rivers, which varies from year to year, and carryover water stored in reservoirs from previous years constitutes the supply of water available to meet both ecosystem and export needs. Upstream reservoir storage capacity affects how much runoff can be captured for managed releases for ecosystem needs and export from the Delta and carried over to subsequent years to buffer year-to-year variations in runoff. Conveyance capacity and physical or environmental restrictions on conveyance operations limit the rates at which water can be exported (and thus annual or seasonal export amounts), while risk of structural failure of Delta levees has implications for long-term reliability of the export system. Reliability of the export supply is also affected by water management strategies and delivery objectives, for example, management to maximize exports each year versus management designed to reduce year-to-year fluctuations in exports. Finally, demand in excess of what the system, with its supply, storage and conveyance capacities and its environmental needs, can provide will, by definition, result in unreliable service.

So what were the causes of the abrupt decline in the Delta water supply in 2008 and 2009 that I described yesterday? In two words: supply and management. 2008 was the second year of what turned out to be a relatively modest three-year drought.[1] In 2007, the first dry year, water managers operated the Delta pumps to export 5.6 million acre feet of water, not a record amount but still the 9th highest in nearly 50 years of Delta pumping. They did this by draining upstream reservoirs filled during the previous wet year and simultaneously shortchanging the estuary of needed freshwater inflows. When 2008 proved to be nearly as dry as 2007, Delta exports didn’t drop because of pumping restrictions to protect fish, or because fresh water was being “wasted to the sea,” or because of problems with conveyance, or because there was not enough reservoir storage—they fell because there was no water. And even though 2009 was not as dry as 2007 or 2008, exports remained low because there was still no water.

While Mother Nature and our mismanagement of the supply she provides was the immediate cause for the sharp drop in exports in 2008 and 2009, the relentless increase in exports during the past several decades to meet ever increasing demands not only drove the ecosystem towards collapse—it set the stage for greater volatility and unpredictability in Delta exports. In essence, because demand has exceeded the capacity of the system, increases in exports have reduced the reliability rather than increased it.

Droughts are a fact of life in California and climate projections suggest that they will become more frequent and intense. So I’ll leave you to decide how well (or how likely) the recently proposed plan to supplement the existing Delta channel conveyance system with new water intakes and a massive tunnel to convey water under the Delta directly to the pumps will address the existing problems and help meet the state-mandated goal for a reliable water supply. But it seems ironic that nearly all of the intense discussions and elaborate analyses of the ongoing Delta planning process have revolved around a plan to meet unnamed (but possibly unrealistic) export targets by rearranging the Delta’s plumbing to guard against catastrophic conveyance failure when the real limiting factor driving water supply reliability is probably Mother Nature and the natural limits of a watershed that, unlike Lake Wobegon’s fabled children, cannot produce “above average” runoff every year.

[1] Respectively, 2007, 2008 and 2009 were the 13th, 15th, and 30th driest years on 82 years.