At least since the 1969 Santa Barbara blowout, we have tended to understand the environmental calamity of major spills through images of oiled wildlife lying dead or in agony along the shore. But animals whose bodies are recovered in a die-off are sometimes said to represent only “the tip of an iceberg”: simply the ones that, by chance, have stranded and been discovered and then reported to authorities. In the Exxon Valdez case, where serious impacts on killer whales, sea otters, and shorebirds took years to manifest themselves, the government came up with a multiplier to account for the numbers of undiscovered dead animals that the oil giant was liable for. In the Gulf of Mexico, the multiplier for some marine mammal species could be very high. According to a recent study, on average, only one in fifty whales and dolphins that die at sea are recovered on the Gulf’s shores.

For marine mammals, the most immediate danger from the Macondo spill was from oiling and inhaling toxic fumes, which can cause brain lesions, disorientation, and death. Going forward, the mechanisms of harm are subtler. As we have seen from the Exxon Valdez, oil can work up the food chain, accumulate in body tissue, induce cascade effects across an ecosystem, and impact wildlife populations for decades afterwards. For now, concern for marine mammals has centered on three particularly vulnerable species: bottlenose dolphins, sperm whales, and Bryde’s whales.

Bottlenose dolphins

The BP disaster happened at a terrible time for the Gulf’s bottlenose dolphins, at the beginning of their reproductive cycle when the coastal population comes nearer to shore. Many observers witnessed them swimming in and around the spill, demonstrating their inability (seen during previous spills) to avoid sheens and emulsified oil. More than one hundred bottlenose dolphins were found dead in the months following the blowout. Now a second die-off has plagued this year’s calving season, with more than 150 additional animals stranded – nearly half of them stillborns or neonates who seem to have been unable to take their first breath. Though some of these animals were visibly marked with Macondo oil, it is not clear what role the spill may have played in the recent strandings, and demonstrating a link is likely to be difficult. Regardless, the latest die-off is extremely concerning to residents and biologists alike. The dolphin communities that have made their homes in the Gulf’s bays, sounds, and estuaries are small and semi-isolated, and the death of even a few babies can have outsized effects on the group.

Sperm whales

Sperm whales have long been attracted to the underwater canyons that extend into the Gulf of Mexico, south of the Mississippi Delta. The waters there are both deep and nutrient-rich, and for the Gulf’s small sperm whale population they constitute a sort of nursery, inhabited by groups of breeding females and calves and immature males who are seldom seen outside of it. Unfortunately, the same waters, which ten years ago became one of the principal targets of deepwater drilling, also played host to the Macondo well. In the wake of the spill, a juvenile was found floating dead in the water – a rare find suggesting the loss of many other whales. Acoustic monitoring by Cornell’s Bioacoustics Research Program confirms that at least some sperm whales remained in the Mississippi Canyon last summer. It is unclear what long-term effects the oil and dispersants may have on these deep-foraging, endangered animals.

Bryde’s whales

Bryde’s (pronounced “Brutus”) whales are by far the Gulf’s most commonly occurring baleen whale species, but their numbers are surpassingly small. Even before the spill fewer than fifty of the whales were thought to remain, according to NOAA’s stock assessments, and these few have been sighted almost exclusively within a single location, the DeSoto Canyon, which lies offshore between Mobile, Alabama and Panama City, Florida. Bryde’s whales rely on their baleen to filter food, putting them at substantial risk of oil ingestion. No one knows how the whales weathered the spill; indeed, they stand as poster children for our astonishing lack of knowledge about the Gulf’s offshore species. Remarkably, we lack even the basic genetic information needed to determine whether they are indeed, as several biologists have theorized, a desperately small, distinct, and isolated population – information that is plainly critical to their conservation.

Life Goes On?

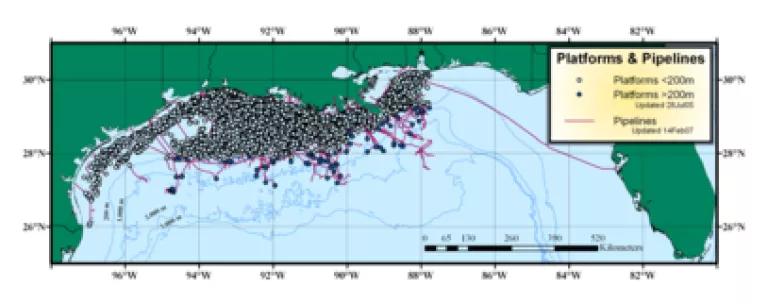

The northern Gulf is one of the most industrialized stretches of ocean on the planet. Its waters are dense with shallow and, increasingly, deepwater platforms, some with undersea structures that themselves can extend dozens of miles around a central hub. Ships and helicopters traverse the area to service them, and a variety of activities potentially disruptive to wildlife, from drilling to explosive platform decommissioning, take place daily.

According to most biologists, the most disruptive of these activities are probably seismic surveys, the industry’s primary tool for offshore exploration in the Gulf and elsewhere, whose high-powered airguns regularly pound the water with sound louder than virtually any other man-made source save explosives. These surveys have a vast environmental footprint, disrupting feeding, breeding, and communication of some marine mammal and fish species over tens or in some cases even hundreds of miles. For the Gulf’s sperm whales, they mean less food: even moderate levels of airgun noise appear to seriously compromise the whales' ability to forage. In an average year, BOEMRE approves more than 60 seismic surveys in the northern Gulf, none of which has undergone review under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. No one knows how the cumulative impacts of this nearly constant disruptive activity will affect wildlife already compromised by the spill.

The Way Forward

• Congress and the Obama administration should adopt the recommendations of the National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling.

• Congress should establish a research fund to ensure that vital research on Gulf marine mammals continues once Natural Resource Damage Assessment funds expire.

• The administration should strengthen mitigation requirements for seismic surveys and other activities that are currently impacting the same vulnerable species affected by the spill.