Last week, the old line corn ethanol lobby, the Renewable Fuels Association, took NRDC, and me in particular, to task for having supported corn ethanol as a bridge to advanced biofuels back in 2005 and for changing my mind as the science changed. Back in 2005, the best peer reviewed science suggested that corn ethanol was modestly better for our climate than gasoline. But as the science changed, especially in 2007 and 2008, as the issue, scope and scale of emissions from indirect land-use change came into focus, NRDC changed its position. Now we're working to end the wasteful corn ethanol tax credit and pass policies that pay for environmental performance to speed the development and deployment of truly low-carbon and broadly environmentally beneficial biofuels. At the same time, and contrary to RFA’s assertions, any pretense that the corn ethanol industry is somehow a partner in laying the groundwork for this transition to advanced biofuels has entirely evaporated over the last year as we watched the industry's lobbysts push to continue to suck up all the public dollars, kill investment in adavanced biofuels, and try to lock our infrastructure into ethanol.

RFA calls the evolution of NRDC's position hypocritical. We call it following the science.

Of course following the science means we have to review a lot of reports on the GHG emissions from biofuels. So also last week, my colleague, Sasha, and I both reviewed an early summary of an analysis forthcoming from Oak Ridge National Labs (ORNL). The analysis provides a detailed look at how the supply of grains and oilseeds shifted in the US while meeting the demands of a growing corn ethanol industry. The problem as Sasha and I pointed out is that the ILUC impacts of our policies have to be calculated compared to a forecast of what land-use would be if we weren't mandating and subsidizing biofuels. The ORNL report only says that supply kept growing but doesn't compare it to anything, so the authors were wrong to claim that the analysis suggested "minimal to zero" ILUC had happened.

Not surprisingly, NRDC's assessment of the ORNL report doesn't sit well with RFA, and one of their lead analysts, Geoff Cooper, commented with obvious frustration on my post:

Well, I’m officially challenging you to join the rest of us in the real world. In the real world, we don’t have a nice and tidy baseline to which we can compare actual events to determine the exact impacts of certain policy decisions. In the real world, we don’t have a “what if” crystal ball that perfectly isolates and reveals the exact reflexes of the marketplace to certain policy decisions. The real world is noisy and messy.

Later in his comment he says:

You’re trying to downplay the importance of exports. But as you know, exports are tremendously important to the whole ILUC calculus. As you know, reduction in exports from the baseline is the primary mechanism by which global commodity prices increase in the economic models used by EPA and CARB. And the price increase is what leads these models to convert land to crops. So why is it improper to suggest that ILUC is unlikely to occur or be significant if exports aren’t decreasing from pre-biofuels era levels (and, rather, are increasing) and global cropland expansion trends are no different today than they were before we were producing biofuels?

Two problems: first as I mentioned earlier, the ORNL doesn't assess any no-policy baseline, and second, Geoff shifts from a baseline comparison to talking about historic trends. Sasha had a great analogy in her post that illuminates why historic trends aren't enough. Imagine, she wrote, you're in a plane trying to go over a mountain. Geoff and the ORNL report would have us believe that as long as you're upward trajectory that's enough, but of course it's not. You have to be going up at a rate that's fast enough to clear the mountain or you'll crash into its side.

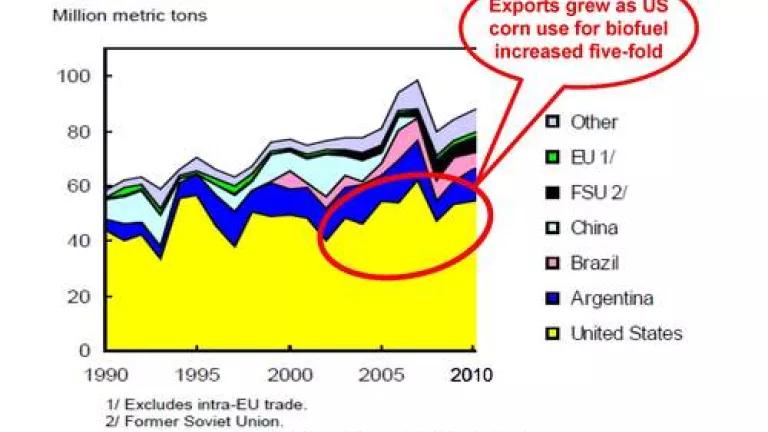

But Geoff's question got me thinking about what has happened to grains and oilseeds since the "pre-biofuels" era. The ORNL presentation includes the following slide making the point that Geoff focuses on--namely, that exports of corn from the US have gone up.

While exports have gone up, that's not enough to get us over the mountain. Furthermore, eyeballing this figure it struck me that the US share of global exports appears to be going down. So I asked Daniel Lorch, a junior researcher here at NRDC, to dig up the USDA data that makes up this figure. It was no easy task, but my eyeballs did not deceive me.

From 1990 to 2010, the US share of world corn exports dropped from 75% down to 54%. The same trend is true in soybeans, total grains and total oilseeds. The U.S. exports have gone up, but their share of the global market has gone down. The U.S. is feeding less and less of the world because demand is growing faster than our supply.

Now I would be the first to say that this is not evidence of ILUC, but it does highlight why simply looking at the supply side of the market is inadequate. What the historical trends actually tell us is that the slope of the mountain is steeper than our airplane's current trajectory. Going up is not enough. Going up a little bit less has real impacts, since even a little bit of clearing in carbon-dense rainforests can result in massive amounts of carbon emissions.

Geoff's right in that I can't prove that ILUC is occurring any more than I can prove that gravity will still apply tomorrow. But that's the funny thing about fundamental laws like gravity and supply and demand--as messy as the real world gets, they still apply. I wouldn't trust a pilot who thought that just going up was enough and I sure hope we won't trust our global energy and climate policy to an industry that thinks rising corn exports means they have no impact on land-use globally.

P.S. To be clear, having the rest of the world feed itself is largely a good thing, but we should support it by reforming our agricultural polices rather than inducing it unintentionally. Smart ag tech transfer policies would encourage higher yields with lower land-use and other impacts. Indirectly induced supply just draws in whatever is cheapest.