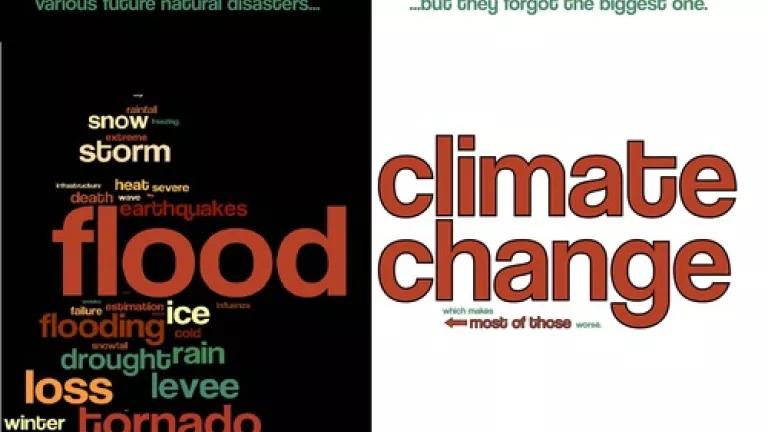

Illinois has recently received approval of its “2013 Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan” (2013 Plan) from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). This document is the state’s disaster preparedness plan, which estimates the future risk of events like floods, droughts, and extreme heat and lays out what actions the state might take to protect itself and its citizens. But the Illinois plan fails to account for perhaps the biggest driver of future natural disasters — climate change.

Illinois makes the mistake of relying exclusively on historical data to estimate the state’s vulnerability to natural disasters. This approach ignores the wealth of information about climate impacts that warns of more flooding, hotter summers, greater likelihood of drought, and more frequent and intense thunderstorms and extreme weather events. When developing a plan intended to anticipate future risks, the state needs to look at climate science to see what the future has in store.

Below is a critique of some aspects of the state’s plan, including information on climate impacts that the state should be considering when preparing for future natural disasters.

Note: NRDC requested and received a copy of the 2013 Plan from the Illinois Emergency Management Agency, but this plan has not been posted on the agency's website, nor did NRDC have permission to post it.

Flooding

Illinois is no stranger to flooding. As the climate warms, flooding will become more frequent. A recent FEMA analysis of climate change and the National Flood Insurance Program shows that Illinois counties can expect between a 40% and 90% increase in the size of areas susceptible to flooding by 2100.

According to the 2013 Plan, about 15% of the state’s land area (7,400 sq. miles) is already prone to flooding and 250,000 buildings are currently located in those flood-prone areas. Illinois has experienced $5.5 billion in flood losses since 1993 and the future price tag will be far greater as flooding becomes more frequent.

Climate change may have already made this kind of localized flooding more likely. Statewide, the annual number of precipitation events greater than 3 inches has increased by 83 percent over the last 50 years, and the amount of total precipitation during these events has increased by 100 percent. As the climate continues to warm, the number of days with rainfall greater than 1 inch is projected to increase up to 30 percent by mid-century.

While major floods on the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers attract the national spotlight, floods are common in Chicago and its suburbs. Cook County has had 11 federally declared emergencies due to flooding since 1991. In those heavily urbanized areas, heavy rains overwhelm stormwater systems, causing localized flooding.

The frequency of larger storms that cause this kind of flooding will increase, according to the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning. Chicago can expect today’s “10-year storm” (4.47 inches of rain in 24 hours) to occur every five years by the end of the century and today’s “100-year storm” (7.58 inches of rain in 24 hours) will become the 50-year storm. It’s worth noting that Chicago has already experienced two 10-year storms in the last four years and three 100-year storms since 1980.

For the Chicago area, heavy rains of this magnitude also means trouble for Lake Michigan and the millions of people who use the beaches and rely on it for drinking water. Heavy rains combined with low water levels on Lake Michigan (see below) causes the Chicago River to “re-reverse” itself and flow back into the lake (as it did on April 18, 2013), carrying millions of gallons of untreated sewage with it.

As the state’s risk of flooding increases with the warming climate, critical state and local facilities will also be put at risk. According to a statewide flood hazard assessment conducted by researchers at Southern Illinois University and included in the 2013 Plan, there are 405 critical state and local facilities located in floodplains including waste-water treatment plants (146), potable-water treatment (33),schools (95), fire stations (48), and police stations (26) and communication facilities (25). It is important to begin planning ahead to determine how these might be protected or relocated.

The increased risk of flooding also increases the risks of levee failures. According to the 2013 Plan, only 10 of the state’s 124 levees in the National Levee Database were rated as “acceptable” and 28 levees were rated as “unacceptable”, meaning the levee has at least one structural or operational deficiency. Illinois is not only likely to see an increase in flooding due to climate change, but also faces the prospect of flooding due to the failure of levees as well.

Drought and Dropping Water Levels

Illinois experienced an historic drought that gripped much of the Midwest in 2012. Average rainfall in June 2012 was 2.3 inches below normal (43% below normal) and 56 sites around the state had record high temperatures that same month. The combination of low rainfalls and high temperatures contributed to a drought that took a heavy toll on Illinois farmers. In Illinois alone, farmers had insured crop losses of nearly $3 billion. Last year’s drought was unusual for its severity but drought is something that parts of Illinois deal with regularly. According to the 2013 Plan, 25 counties have declared a drought emergency 15 or more times between 1990 and 2012.

Again, the state’s disaster preparedness plan relies solely on historical data to determine the severity and frequency of droughts the state should be prepared for. But the climate science tells us that droughts are even more likely in the future.

While annual average precipitation is projected to increase slightly (2 to 8 percent) by mid-century, average precipitation during the summer is projected to decrease by up to 10 percent. This would coincide with projected summer temperature increases of 5 to 6°F. Hotter temperatures combined with decreased precipitation could contribute to drier soils and more droughts. A report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found that the extreme heat seen in the 2012 drought is now four times more likely to happen than in the past because of climate change.

Similar to the risk of drought is the risk of dropping water levels in the state’s lakes and rivers. In 2012 water levels on the Mississippi River were so low due to the drought that barge traffic was impeded between St. Louis and Cairo, Illinois. On Lake Michigan, lake levels were their lowest since 1964, the all-time low. Lake Michigan has been dropping steadily since the 1970s and many projections indicate that lake levels will continue to fall as the climate warms.

Extreme Heat

One of the easiest to understand impacts of a warming climate is the increased risk of extreme heat. But even here, the state’s disaster preparedness plan fails to account for, or even mention, the impacts of climate change on future risks of extreme heat.

According to the 2013 Plan, Illinois currently averages 10 days at or above 90°F in the northern part of the state compared to just over 40 days in the southern part. In 2012, over 110 heat records were broken across the state. By mid-century, Illinois summers are projected to feel more like summers in southern states like Louisiana or Arkansas.

Extreme heat is not just an uncomfortable inconvenience, but a serious public health threat. In 1995, a heat wave struck Illinois that killed 583 people — 504 in Chicago alone. By the end of the century, an estimated 166 to 2,217 people could die each year from heat waves in Chicago, depending on how much our nation reduces emissions (Peng, et al, Environmental Health Perspectives, 119, 5 (2011): 701-706). Heat waves like the one in 1995 may occur 2 to 5 times per decade by mid-to end of the century.

As the climate warms, Illinois can expect to see the number of days exceeding 95°F increase by 10 to 20 days in northern regions of the state and by 20 to 30 days in southern regions by mid-century. And the annual number of consecutive days exceeding 95°F is projected to increase by 80 to 100 percent across Illinois. By the end of the century, the number of days exceeding 100°F annually in Chicago could increase by four to fifteen-fold.

It is important to anticipate these increased risks, as cities and towns should begin planning on where to locate emergency cooling centers. The increased temperatures will also put a greater strain on electricity supplies, as people turn to air conditioning to bring relief from the heat. The state should also be planning on how it will meet this new energy demand.

Conclusion

Preparing for natural disasters can no longer be just an exercise in learning from the past. States must also take into account new information on how climate change will affect the frequency and the severity of natural disasters and related changing weather patterns.

Relative to other states, Illinois does a pretty good job developing its disaster preparedness plan through the use of historical data. But we know that climate change is occurring, it is already having an impact, and the science gives a pretty good idea of what the future risks will be — but these risks are not factored into the plan that FEMA recently approved for Illinois.

Even though the full magnitude of some climate risks cited may not be fully realized for decades, it is important that Illinois begin preparing for those challenges today. It is also important to remember that the projected climate impacts are estimates of average future conditions, so the odds of larger storms or longer droughts are slightly increased each year as the climate warms.

In developing a disaster preparedness plan, states are supposed to anticipate a wide range of natural disasters they might have to respond to in the future. Thinking ahead allows states and communities to anticipate problems and possibly avoid them, not just respond to them.

Relying solely on historical data to gauge the risk of natural disasters means Illinois is only looking at part of the information available. Only by conducting a full assessment of climate risks can Illinois make proper use of scarce resources to prepare for the changing weather patterns and natural disasters of the future.