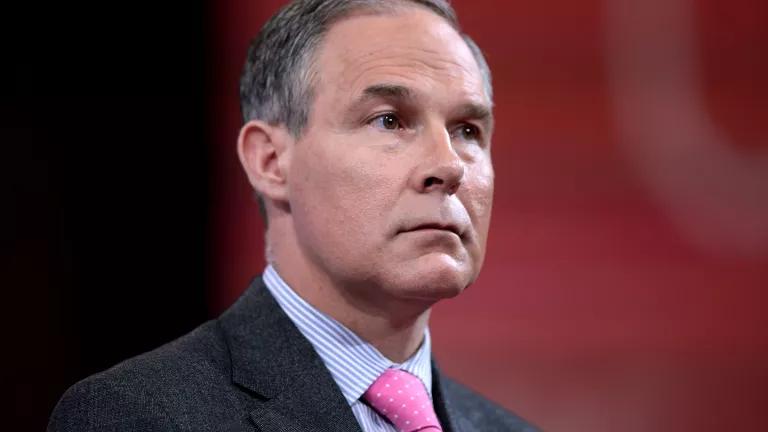

Scott Pruitt Wants to Take Us Back to the ’50s

The incoming head of the EPA believes states should be in charge of their own environmental regulations. Been there, done that, got the oil-soaked T-shirt.

Scott Pruitt, Donald Trump’s pick to lead the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, has sued to block every major EPA regulation in recent years—rules to limit carbon emissions, reduce interstate air pollution, protect us from airborne mercury, and improve clean water standards. As Oklahoma attorney general, Pruitt has taken the EPA to court so often that it has become a running joke—even to him.

There are sometimes good reasons to sue the agency; a coalition of progressive states, for example, sued to force the Bush-era EPA to regulate carbon emissions. But Pruitt’s motives are different. He claims to be waging a crusade against federal regulatory power, arguing that the EPA lacks authorization to issue its rules. Yet his misguided litigation spree to block its anti-pollution measures has resulted in loss after loss. And his ideas about state sovereignty fly in the face of a decades-old consensus granting the federal government primacy in controlling pollution.

This raises a more worrying possibility: Is Pruitt’s stated rationale for his anti-EPA campaign merely a pretext for pursuing a pro-industry, anti-environment agenda? It certainly looks that way. Should he succeed this time, he’ll undermine a regulatory system that has steadily improved human and environmental health for more than four decades. But in the spirit of our litigious nominee, let’s consider his argument.

“Overreach”

Pruitt regularly accuses the EPA of “overreach.” By this he means that the agency issues regulations more stringent than Congress has asked for, and that it has inappropriately usurped state power.

The Supreme Court has disagreed. When Pruitt sued the EPA in 2011, seeking to block rules that prevent states from polluting the air of their downwind neighbors, six of the justices—including two conservatives—ruled against him. In another lawsuit, Pruitt challenged the EPA’s efforts to limit mercury and other airborne toxins from power plants. The court’s decision, although complicated, let the rule stand.

The EPA won these cases because our environmental statutes are clear: Congress has instructed the agency to aggressively regulate pollution. When judges admonish the EPA for misinterpreting its legislative instructions, it’s often because the agency has been too lax. The D.C. Circuit, for example, accused George W. Bush’s industry-friendly EPA of living in a “Humpty Dumpty world” and “deploy[ing] the logic of the Queen of Hearts, substituting EPA’s desires for the plain text” when it tried to sabotage key provisions of the Clean Air Act by loosening restrictions on corporate polluters.

Pruitt’s allegation that the EPA serially oversteps its legislative authority is wrong. But his claim that the EPA tramples upon state sovereignty is dangerous. Pruitt is trying to resuscitate a scheme that was proved disastrously ineffective decades ago. The EPA was created precisely because the states failed so miserably at environmental protection.

Behold the Pruitt-ian utopia: the 1950s and ’60s United States, in which the federal government sat back and let the states protect our environment. The country was polluted from sea to shining sea. Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, her manifesto exposing the “chemical death rain” of DDT and other pesticides falling on farms across the country. Oil-covered debris floating in Ohio’s Cuyahoga River caught fire, giving Americans the spectacle of a body of water drowning in flames. Algal blooms fueled by phosphorus pollution had turned Lake Erie into a massive dead zone. Angelenos wiped tears of air pollution away from their eyes and brought their children to environmental rallies wearing gas masks. And, on November 23, 1966, nearly eight million New Yorkers awoke to a city choking on smog so thick, they couldn’t see across Central Park.

Finding a State–Federal Balance

Pruitt likes to depict the EPA as an all-powerful environmental dictator that sweeps away state authority. History proves otherwise. “The federal government initially put the ball in the states’ courts for air and water quality,” says environmental historian Cody Ferguson. “When enforcement was too lax, Congress assumed greater authority.” This process has continued over the years.

Take air pollution as an example. Federal laws in the late 1960s urged the states to improve air quality but did little else. When states didn’t respond, Congress passed the landmark 1970 Clean Air Act, which set minimum standards, established deadlines to achieve them, and granted federal regulators plenary authority to intervene if the states failed.

“Congress adopted the 1977 and 1990 Clean Air Act amendments because the states had shown themselves incapable of or unwilling to reduce air pollution at the pace and degree that Congress wanted following the original 1970 Act,” notes John Walke, director of NRDC’s Clean Air Project.

The EPA intervened for a number of reasons, often compensating for a lack of resources and expertise. But primarily the agency acted because the states—in a desperate race to grow their economies—deprioritized clean air and water.

“There was competition among the states for industry,” notes A. James Barnes, who served as special assistant and later chief of staff to the EPA’s first administrator, William Ruckelshaus. “It was not unusual to see ads in northern newspapers inviting industry to move to southern states because the environmental regulators would be easier on them.”

According to Barnes, state governors personally interceded to prevent their attorneys general from prosecuting major polluters, either to protect jobs or keep the industries in their back pockets. The consequences were impossible to ignore. Barnes grew up near Michigan’s Flint River, which often ran red or green because of a paint facility that discharged untreated tints into the water. The impacts of these laxities traveled far beyond state borders. Water and air pollution—like water and air itself—is not static.

While Pruitt depicts the EPA as a villain concentrating regulatory power at the federal level, it was more often Congress that took action in response to public demands—and with good results. During the EPA’s existence, emissions of the most common air pollutants have dropped by an average of 70 percent. Those reductions have prevented hundreds of thousands of early deaths and millions of lost work days. Take as an example the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards, a rule that Pruitt has tried, and so far failed, to nullify. These regulations will prevent 11,000 premature deaths, 4,700 heart attacks, and 130,000 asthma attacks every year. The benefits are nine times the cost. The need for the rule could not be more evident.

Ideology First

Pruitt belongs to a movement that believes the federal government has little role in safeguarding our well-being. The problem with ideologues like him is that they don’t let facts get in the way of their preconceived notions. History proves that weakening or eliminating the EPA will result in dirtier air, more polluted water, and environmental disasters on a scale not seen for decades.

Pruitt’s arguments against the EPA’s life-saving rules are so flimsy that it’s hard to see how the general public would ever get behind them. But we do know he’s got one sector squarely in his corner. In 2014, the New York Times revealed that a letter sent to the EPA with Pruitt’s signature was actually authored by lawyers for one of Oklahoma’s largest oil and gas companies. Pruitt has never denied the report. When he was nominated, fossil-fuel interests celebrated, while environmental and public health advocates cringed.

Scott Pruitt clearly has no interest in safeguarding our health and environment. He serves his extremist ideology. He serves his patrons in the oil industry. But he won’t serve you.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

How to Fight Trump’s Pro-Polluter Agenda and Win? Take Him to Court.

The Uinta Basin Railway Would Be a Bigger Carbon Bomb Than Willow

Mercury’s Journey from Coal-Burning Power Plants to Your Plate