Denying the Deniers

The Paris climate agreement just took away one of climate skeptics’ favorite arguments for inaction.

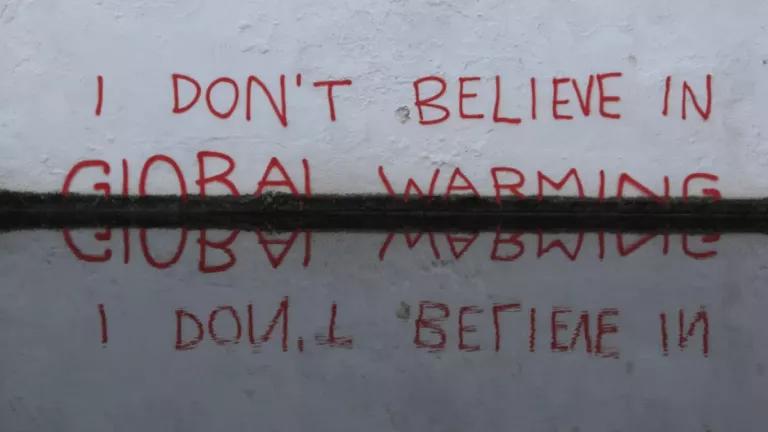

Photo: .Martin./Flickr

If you’re looking for post-COP21 wrap-up pieces that spell out precisely what the recent international climate agreement “means” as a scientific document, a technical document, or a political document, you’re in luck. As the ink dries on the biggest and most far-reaching climate pact in history—just signed and formalized last Saturday—there’s no shortage of detail-rich articles and explainer-type pieces out there this week that will help you understand how the 190-plus signatories plan to meet their respective emissions targets, and how the collection of those commitments just may keep the rise in global temperature to no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius. For climate-minded policy wonks, Christmas came a little early this year.

But one important question has yet to be asked and answered: What does COP21 mean for climate deniers?

For those in the business of sowing doubt on climate change, 2015 has been a rough year. Back in June, Pope Francis issued a sweeping and headline-grabbing encyclical that essentially condemned climate inaction as immoral. No sooner had deniers finished spinning the move as a misuse of papal authority than data started rolling in to suggest that 2015 would very likely be the hottest year on record, just edging out the previous titleholder: 2014.

And then, during the first two weeks of December, the entire world basically came together to signal humankind’s dedication to fighting climate change on a global level. Adding insult to injury for the doubtmongers was the fact that when a major denialist group tried to score rhetorical points by holding its own rally-the-troops event in Paris during the U.N. conference, the few who showed up were mostly protesters or environmental journalists. Perhaps they were curious to know what a swan song sounded like. (In this particular case, it sounded like self-righteous bleating mixed with a good deal of whimpering.)

I hate to be the bearer of bad news (although let’s be honest: Climate deniers aren’t in the habit of heeding warnings anyway), but I’m afraid that the coming year doesn’t bode very well for them, either. A New York Times poll conducted earlier this year found that an overwhelming majority of Americans—83 percent of them, including 61 percent of those who self-identify as Republicans—believe that we must act now to reduce emissions, lest climate change become “a very or somewhat serious problem in the future.” Organizations that once trumpeted their climate skepticism are now running away from the label; politicians who used to openly profess their doubt are now equivocating, aware of the terrible optics. In fact, were we to plot the cultural relevance of climate deniers from the beginning of the 21st century to the end of the current decade, the resultant graph would probably resemble, oh, I don’t know . . . a hockey stick, but with its blade aimed sharply downward.

The consensus reached last week has altered the terms of our climate conversation. For years, deniers were able to hijack the discourse, stalling actions to curb carbon pollution by insisting that the issue wasn’t settled as a matter of empirical science. Their arguments relied on a willful misrepresentation of the word theory, and even more on the sense—reinforced by the breakdown and failure of previous climate talks—that the world community wasn’t even capable of agreeing on the nature or scope of the problem, much less on how to solve it.

Paris, however, changed everything. Officials from the nearly 200 nations represented at the summit weren’t there to debate whether climate change existed, or how severe it was; they were there to debate the best and the fairest ways to go about ending it. Their attendance at COP21 presupposed their acceptance of the science, as well as their moral seriousness.

It’s a truism of classical mechanics that inertia is the most powerful force in the physical universe. And it has long been recognized that cynicism is one of the most powerful forces in the political universe. Combined, the two would seem to be virtually unstoppable. To the extent that climate deniers have ever had faith in anything, perhaps they believed in this basic idea: that climate inertia—as a function of political cynicism—would always win out in the end.

But something else won instead: hopeful determination, rooted in science and pragmatics. The success of COP21 won’t completely silence the deniers, of course; some remnant of their irksome ilk will always remain. Still, from this point forward—with the world now united in opposition to their bad faith and stalling tactics—they’ll have to get used to not being seen as champions of “further debate.” Instead they’ll be regarded as kooks and cranks, on par with those who would continue to deny heliocentrism or the roundness of the Earth.

Science deniers are entitled to their opinions, of course. But they’re no longer entitled to be taken even remotely seriously by the rest of us. We’ve got bigger and better things to do.

This article was originally published on onEarth, which is no longer in publication. onEarth was founded in 1979 as the Amicus Journal, an independent magazine of thought and opinion on the environment. All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of NRDC. This article is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the article was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the article cannot be edited (beyond simple things such grammar); you can’t resell the article in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select articles individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our articles.

Electric vs. Gas Cars: Is It Cheaper to Drive an EV?

Liquefied Natural Gas 101

The Uinta Basin Railway Would Be a Bigger Carbon Bomb Than Willow