Denver Doesn’t Want Its Edible Bounty to Go to Waste

Food waste and food insecurity are two sides of the same coin. This creative initiative aims to tackle both.

City Harvest’s Jered Ratschkowsky (left) with Andrew Sanford (center) and Matt Karm of We Don’t Waste during a food delivery.

Matt Nager for NRDC

One of Colorado’s largest food recovery organizations started out of the back of Arlan Preblud’s Volvo. An avid foodie, Preblud was deeply bothered that restaurants tossed out so much of their leftovers while many in the Denver community went hungry. So in 2009, he began reaching out to restaurants and caterers to collect untouched short ribs, pasta, and fruit salads, among other dishes. He loaded food into his vehicle and drove it directly to organizations that feed those in need, working quickly to ensure any perishables were served within a health-safe window.

The response to this food rescue operation was overwhelmingly positive. So Preblud quickly made some business upgrades. He added refrigerated vehicles to his fleet and rented space for a distribution center.

A decade later, Preblud’s organization, We Don’t Waste, has grown into a team of 10 employees. The crew picks up excess food from 150 donors—caterers and groceries, hotels and schools, cookie and cupcake businesses, and even the Denver Zoo—and delivers the fare to 60 agencies. From these hubs, the food gets distributed to an additional 130 entities, such as food banks, services for young mothers, and homeless shelters.

“Denver has an ecosystem of incredible local nonprofits doing work on food issues,” says Madeline Keating, the city lead in Denver for Food Matters, a project of NRDC with support from the Rockefeller Foundation. Yet many “don’t have the resources and network to connect with each other,” she adds. Food Matters works to unite and streamline these efforts in its mission to tackle the interrelated problems of food waste and food insecurity.

The project addresses food waste through three strategies: educating consumers and businesses, rescuing surplus food, and recycling food scraps. In turn, various composting initiatives help support Denver’s small-scale farming initiatives in neighborhoods that lack adequate healthy food options.

Matt Nager for NRDC

Currently, in partnership with the Denver Department of Public Health & Environment (DDPHE), the project is providing grants to 10 small businesses and nonprofits, including We Don’t Waste. (Other recipients include a bike-powered compost business that hauls more than 6,000 pounds of compostable food per week, and a nonprofit community outreach program that teaches food preservation techniques.)

Meanwhile, in Baltimore, the other Food Matters model city, NRDC is helping local officials advance their goal to cut commercial food waste by 80 percent by 2040. Given that more than $200 billion worth of food is going uneaten annually in the United States, NRDC hopes to see communities around the country replicate the initiatives being tested out in these two cities. This enormous waste exacts high environmental costs: the wasted water and energy resources used to grow and transport produce and the climate-busting methane produced by rotting food. “Sending organic matter to landfills has a big impact on climate change,” Keating says. “If food waste were a country, it would be the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world.”

Healthier Childhoods Take Root

In 2018, an estimated 22,300 children living in the Denver area didn’t know where their next meal would be coming from. Across the city, the child food insecurity rate is 16.2 percent. In its Food Action Plan released last year, Denver lists feeding the hungry as one of its primary goals. Specifically, the city seeks to reduce the number of food-insecure households by 55 percent by 2030.

In two low-income neighborhoods, the staff of We Don’t Waste’s Mobile Food Market sets out recently rescued fresh strawberries, avocados, poblano peppers, tortillas, and other foods on tables, like a farmer’s market bounty. Before visiting community-based agencies, the workers distribute Spanish and English flyers inviting local residents to “shop” the tables for fresh, healthy foods.

Half the food Preblud’s group distributes is fresh fruit, vegetables, lean proteins, and dairy. “Grocery stores won’t take an imperfect bell pepper,” he says. “Our mission is to support the Denver community by receiving unused food, keeping it out of the landfill, and feeding people.”

Using Denver as a case study, a 2017 NRDC report examining urban food waste demonstrated that if food were rescued in time, seven million additional meals could be placed on needy tables in the city over the course of a year. The result would close Denver’s meal gap by 46 percent.

Empowering residents to grow their own food, such as through community and schoolyard gardens, is another goal of Denver’s food action plan. Organizations like Children’s Farms of America (CFA)—also a Food Matters grantee—are helping to meet this goal. CFA runs a variety of after-school clubs, school-based programs, summer camps, and cooking clubs for 500 children per year. On five micro-farms, located on school, church, and other local plots in Montbello, a neighborhood without a grocery store, participants learn to cultivate organic baby tomatoes, carrots, cabbage, okra, and collard greens, among other much-needed produce. CFA farms range from an eighth of an acre to a full acre. Some grow more than 80 pounds of fresh food daily and even have goats, chickens, and other livestock. Children help distribute produce at a weekly farmers’ markets or at no-cost community grocery stands.

“People shouldn’t have to be dependent on someone else for a resource they can create for themselves,” says Donna Garnett, CFA’s board president. “Children are the change agents for helping their families reinvent growing spaces, rescue food, compost food waste, eat better, and live healthier.”

Restaurant Rescue

As in most other U.S. cities, the largest chunk of Denver’s food waste (41 percent) is generated residentially, according to NRDC’s report. Per person, Denverites toss more than four pounds of food weekly—three-quarters of which is perfectly edible. Restaurants are the next-largest generator at 25 percent, followed by an assortment of food-related industries including manufacturers, wholesalers, grocers, schools, and hotels.

So, in 2018, as part of the Food Matters Project, DDPHE inspectors created “No Plate Left Behind” food donation guidelines and began offering information, via brochure and in person, to licensed food facilities on their role in cutting back their waste. The brochure describes foods that can and can’t be donated, food donation safety, and donation locations.

And just this month, the city kicked off a “zero-waste restaurant challenge,” says Laine Cidlowski, DDPHE’s food system administrator. Recruited restaurants are learning how to minimize excess, for example by more carefully determining the correct quantities of ingredients and better explaining their portion sizes to customers.

Cutting waste decreases environmental impact, Cidlowski notes, but it also creates a win-win where a restaurant’s bottom line is concerned. “If a restaurant is more efficient with food, it’ll benefit from more profit,” she says.

Creating a Composting Culture

Denver city officials have committed to reducing the amount of residential food waste sent to the landfill by 57 percent by 2030—but meeting that goal won’t be easy. Currently, only 6 percent of Denver’s homes are signed up to have their compostables hauled away in the green composting bins the city provides, a service residents must pay to use.

To help convert more of its population into home composters, the city offers a Master Composter program. Its participants get trained in composting science, then perform community outreach and teach their skills to others. The city’s solid waste management program is also informing consumers about ways to get more use out of their compost bins and cut down on food waste, using tools from NRDC’s Save the Food initiative.

Innovative startups are also hitting the streets to fill in the gaps. Grant recipient Scraps LLC, a bike-powered compost service, hauls commercially compostable material from more than 400 customers in 30 neighborhoods. Scraps serves apartment buildings and restaurants unable to access city compost services.

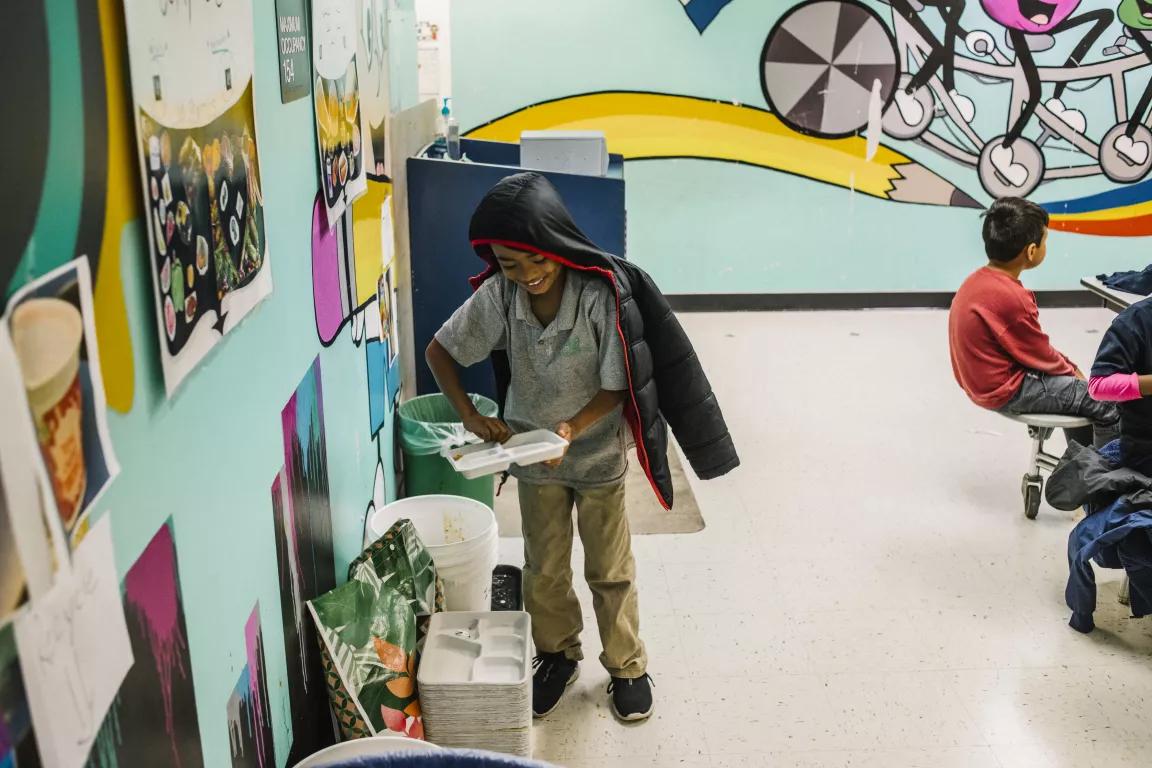

Meanwhile, the nonprofit Consumption Literacy Project, another grant recipient, is engaging kids in the art and science of composting. Soil and nutrients may seem abstract to young children, but “kids understand food,” says the group’s founder, Austine Luce. In 2015 she started worm composting projects in nine Denver and Jefferson County schools, working with children in kindergarten through fourth grade.

Kids get a hands-on understanding of food’s life cycle by adding snacktime leftovers to a small worm bin and examining the difference between soil and dirt with microscopes. Younger kids sometimes scream upon first encountering wriggling earthworms, Luce says, but repeated exposure helps minimize any fear. Soon enough, when teachers pull out the worm bin after snacktime, the children’s eyes grow big with wonder and fascination. Many are holding the worms in their hands by the semester’s end.

In Denver, composting is part of a larger social justice movement. “The injustice in this community is that many people struggle with economic resources and access to food,” Luce says. Montbello youth are capturing food waste and creating healthy soil that will be used by CFA to grow food for the community.

“We’re creating young scientists and young activists, “ Luce says. “But it’s also a way to make classroom science fun again, and these youth are becoming a part of their community transformation.”

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

In Planning for Climate Change, Native Americans Draw on the Past

Under “Food Apartheid,” Urban Farms Are More Important Than Ever

A Mississippi Tribe Is Growing Its Own Organic Movement