Out of Solitary Confinement

Shot, stuffed, and stuck with reptiles for decades, these hyenas are headed to their rightful home in the museum.

This is an adventure-mystery story that began more than a century ago and stars four striped hyenas. The characters are admittedly lacking in traditional wildlife charm—they don’t have the grandeur of the lion or the cute factor of the panda—but they’re stuffed with intrigue, nonetheless.

They’re also literally stuffed: The burly carnivores have spent a sedate (and stiff) afterlife at the Field Museum in Chicago, where they have stood frozen in time in a glass case, gathered around what looks to be a giraffe’s rib cage. To add insult to injury (a naturalist shot them in the late 1800s), the hyenas have been kept in the museum’s Reptile Hall.

That’s right, the reptile exhibit—next to the climbing lizards. Oh, the indignity.

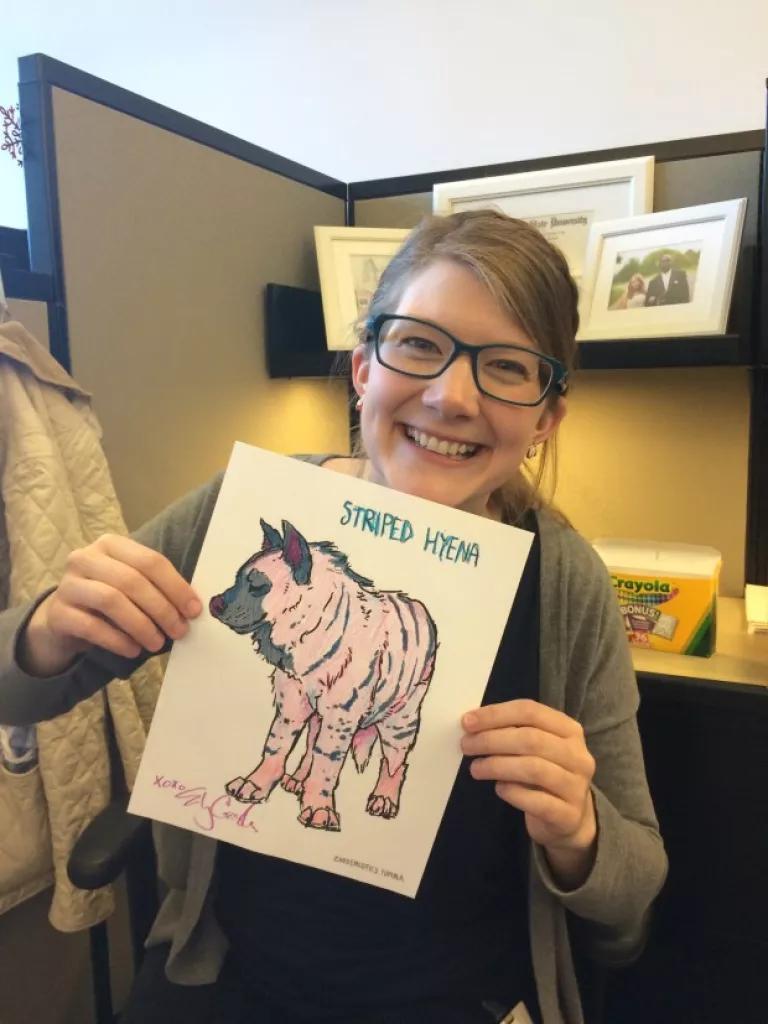

“Once you notice it, it’s so obvious that they’re out of place,” says Emily Graslie, the museum’s chief curiosity correspondent (her real title). She is the mastermind behind Project Hyena Diorama, an effort to build a detailed exhibit for the carnivores. In April, Graslie launched an Indiegogo campaign to crowdsource the $170,000 needed for a new diorama shell, painted landscape mural, and any restorative touch-ups for the hyenas (one, for instance, has lost a little fur behind its left shoulder).

Once abundant in northern Africa and central Asia, wild hyena numbers have dwindled to around just 10,000 individuals, thanks to hunting (the animals are persecuted throughout their range as pests) and loss of its prey base. If striped hyenas go extinct in the wild, says Graslie, museums and zoos might be the only places anyone will ever see them. “This diorama is a way to give people an appreciation of a species that might not still be in the wild in another 100 years,” says Graslie, who affectionately calls the loathed creatures “underdogs”—then quickly points out that they aren’t actually dogs.

The tale of the wayward hyena quartet starts with Carl Akeley, the museum’s first taxidermist and the father of modern taxidermy. (He’s also renowned for killing an 80-pound leopard with his bare hands, inventing a motion-picture camera adopted by Hollywood, and being buds with fellow conservationist Teddy Roosevelt.) When news hit in the 1890s that a livestock disease, the Rinderpest virus, was wiping out wild ruminants in northern Africa, the Field Museum sent a party, including Akeley, across the Atlantic to collect specimens. The bounty of some 200 mammals included four hyenas, which Akeley mounted in 1899 in Chicago.

Now the hyenas are on the move again, so to speak. A few weeks ago, the museum painted paw prints outside their glass case—a sign that these carnivores are finally on their way to their rightful home in the Hall of Asian Mammals. Visitors can follow the tracks, which would lead them away from the reptiles, through the hall of birds, past the African mammals and notorious man-eating lions of Tsavo, before ending in front of an emerald wall.

That the green, rectangular expanse is exactly the same size as the 19 other dioramas in the Asian mammal hall is no accident; of the 20 planned dioramas here, all but one were completed by the 1930s. While there’s no record of why construction stopped so close to finishing the project, Graslie notes that the standstill coincided with the Great Depression. Way back when, this was the hyenas’ intended home.

Graslie was on hand when workers recently pried open the exhibit to reveal a mishmash of items boarded up for nearly 100 years. What had been gathering dust inside included 1930s newspapers, empty specimen drawers, and extra plants not needed for the other, completed exhibits. Soon, this space will become a carefully crafted replica of the hyenas’ natural arid habitat. “It will be completely authentic,” says Graslie. “It could be a night scene, since these guys are nocturnal.” (The exhibit director will make that call, she adds.)

The fund-raising campaign wraps up on May 20, and a team of builders, artists, and scientists will then delve into creating the diorama, which is slated to be unveiled in January 2016. “I tell people, even if you can’t come to see it for 20 or 30 years, when you do visit, it’ll still be here,” says Graslie. “And you’ll look at it and be transported to another part of the globe.”

And so the hyenas will have their happy ending and hopefully inspire the protection of their cousins out there right now, on Africa’s savannas or Asia’s scrublands, gnawing on some ruminant’s ribs.

So, does the museum hold other mysteries? “Oh yeah,” says Graslie. “There probably aren’t any more hidden dioramas. But we’ve got 27 million artifacts—only 1 percent of which are on display.” That’s certainly rich pickings for someone with “curiosity” in her title.

This article was originally published on onEarth, which is no longer in publication. onEarth was founded in 1979 as the Amicus Journal, an independent magazine of thought and opinion on the environment. All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of NRDC. This article is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the article was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the article cannot be edited (beyond simple things such grammar); you can’t resell the article in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select articles individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our articles.

Protecting Biodiversity Means Saving the Bogs (and Peatlands, Swamps, Marshes, Fens…)

How to Make an Effective Public Comment

From Dams to DAPL, the Army Corps’ Culture of Disdain for Indigenous Communities Must End