Regenerative Agriculture 101

The methods of regenerative agriculture are meant to restore soil and ecosystem health, address inequity, and leave our land, waters, and climate in better shape for the future.

Radical Family Farms in Sebastopol, California

John Brecher for NRDC

NRDC interviewed more than 100 farmers and ranchers who are building healthy soil and growing climate-resilient communities across the country. This guide incorporates much of what we learned.

What is regenerative agriculture?

As a philosophy and approach to land management, regenerative agriculture asks us to think about how all aspects of agriculture are connected through a web—a network of entities who grow, enhance, exchange, distribute, and consume goods and services—instead of a linear supply chain. It’s about farming and ranching in a style that nourishes people and the earth, with specific practices varying from grower to grower and from region to region. There’s no strict rule book, but the holistic principles behind the dynamic system of regenerative agriculture are meant to restore soil and ecosystem health, address inequity, and leave our land, waters, and climate in better shape for future generations.

Land-Grant program associate Teresa Kaulaity Quintana (Kiowa) examines crops at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) campus in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The demonstration garden promotes Indigenous agricultural methods such as waffle gardening and flood irrigation practices using traditional crops of the Southwest.

Lance Cheung/USDA

It’s important to appreciate that this is not a new idea and not all who practice these principles use the label. In fact, Indigenous communities have farmed in nature’s image for millennia. “The regenerative agriculture movement is the dawning realization among more people that an Indigenous approach to agriculture can help restore ecologies, fight climate change, rebuild relationships, spark economic development, and bring joy,” says Arohi Sharma, water and agriculture policy analyst at NRDC. Sharma is part of the team from NRDC’s Nature program that interviewed more than 100 regenerative farmers across the United States to inform recommendations on creating a food system that can help fight our climate crisis.

Regenerative agriculture is a philosophy

At its core, regenerative agriculture is farming and ranching in harmony with nature. Practitioners take a broader view of their role in the world, especially in terms of soil and nutrient cycles. “We need to realize that working landscapes provide not just products but also ecosystem services like carbon sinks, water recharge, and evolutionary potential,” says Leonard Diggs of Pie Ranch, an incubator farm where he teaches regenerative agriculture. “We need agriculture that does not lose our carbon and does not deplete our people.”

By contrast, the industrial agricultural system that dominates Western food and fiber supply chains incentivizes practices that promote soil erosion at a rate of 10 to 100 times higher than soil formation; nutrient runoff and harmful algal blooms in freshwater and coastal systems; and monocropping and other threats to local biodiversity, including critical pollinators. These systems compartmentalize natural resources and focus on the yields of individual crops.

Regenerative agriculture principles

“When we speak with farmers and ranchers focused on regenerative agriculture, they tell us that their notion of ‘success’ goes beyond yield and farm size,” says Lara Bryant, deputy director of water and agriculture at NRDC. “It includes things like joy and happiness, the number of families they feed, watching how the land regenerates and flourishes, the money saved from not purchasing chemical inputs, the debt avoided by repurposing old equipment, and the relationships built with community members.” Below are some of the principles they utilize to achieve these goals.

Nurture relationships within and across ecosystems

Regenerative growers foster and protect relationships—between people, lands, waterbodies, livestock, wildlife, and even microbial life in soil.

Alyssa Barsanti moves a chicken tractor at her farm, Marigold Livestock Co., on leased public lands in Pitkin County, Colorado. The scratching action of the birds helps control pests and the nitrogen- and phosphorus-rich manure fertilizes the pasture.

Jeremy Swanson for NRDC

For instance, when we took animals out of cropping systems (a practice that started with poultry in the 1950s and expanded to beef and pork in the ’60s) and separated them into confined facilities and feedlots, we introduced a host of ethical and ecological problems, including the rise in antibiotic-resistant bacteria and harmful algal blooms. But fostering relationships between animals and the land can help cycle nutrients, increase water retention (from the organic matter left behind by animal manure), and curb weed and pest problems without the use of chemicals.

Prioritize soil health

While the techniques for caring for the soil vary with the context of each farm, generally, regenerative growers limit mechanical soil disturbance. Instead, they feed and preserve the biological structures that bacteria, fungi, and other soil microbes build underground—which provide above-ground benefits in return.

Prairie strips planted on a farm near Traer, Iowa, display first-year growth. The strips help protect soil and water while providing habitat for wildlife.

Lynn Betts/USDA NRCS

Reduce reliance on synthetic inputs

Regenerative farmers and ranchers make every effort to reduce their reliance on synthetic inputs, such as herbicides, pesticides, and chemical fertilizers. In the process of prioritizing soil health, many growers naturally use fewer chemical inputs. Instead, as beneficial insects and wildlife return and diverse crop and livestock rotations disrupt weed cycles, the ecosystem becomes more resilient. And with fewer toxic chemicals, there are reduced human health risks as well as increased financial independence from avoiding the recurring costs of synthetic inputs.

Farm manager Noland Johnson shows handfuls of tepary beans grown at Papago Farm on the Tohono O'odham Nation in southern Arizona. The drought-resistant beans are native to the southwestern United States and Mexico and have been farmed since pre-Columbian times.

Chris Richards /The New York Times via Redux

Nurture communities and reimagine economies

Many regenerative farmers begin their practice with the aim of growing healthy food for their families and communities. They consider it essential to treat their farmworkers, apprentices, and other laborers with respect, and to provide on-farm staff with fair wages and a seat at the decision-making table. And many of these growers have a deep appreciation of the social and historical contexts in which they operate. They acknowledge how unjust policies have shaped American agriculture, even though our food systems were built by Black and Indigenous communities.

Social inequities in American agriculture

For many practitioners, regenerative agriculture is an approach to remedying long-standing social injustices, including systemic discrimination that has denied farmers and ranchers of color access to land tenure and support services.

“These interviews—and these principles—helped our team realize that advocating for regenerative agriculture needs to address social, cultural, and historical issues,” says Ellen Lee, NRDC program associate.

A Black farmer plows his four-acre field in Rappahannock County, Virginia, in May 1940.

Jack Delano/Farm Security Administration

Back in 1920, there were nearly one million Black farmers in the United States. But after more than a century of land theft, racist polices, and discrimination, that number is closer to 45,000 today—out of an estimated 3.4 million farmers, according to census data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). White farmers, by contrast, now own 98 percent of the land in America. And yet, even as we acknowledge that historic racial and gender inequities have contributed to unequal access to wealth and land ownership, “doors continue to be closed to many Black farmers,” notes John Wesley Boyd Jr., president and founder of the National Black Farmers Association. “Our members face enormous challenges—including a system that disproportionately leaves them behind.”

At the federal level, steps have been taken to address equitable access to land, training, and credit and to support underserved producers—including funding and directives to shift the decades-long legacy of racial discrimination at USDA. But significant work remains. “The way we see it, regenerative agriculture goes beyond on-farm practices and techniques to encompass broader social and cultural components,” says Lee. “Policies that advance regenerative agriculture should avoid exacerbating deep-seated inequities.”

Why regenerative agriculture?

The care and creativity regenerative growers showcase yield benefits on and off the land. They grow food and fiber, draw down carbon, conserve water, replenish waterways, grow healthier foods, reduce their use of synthetic inputs, employ people within their communities, and ensure the long-term vitality of the land.

An earthworm in the soil of a no-till farm field

Ron Nichols/USDA NRCS

Ecological benefits

- Improvements in soil health and fertility—the foundation of healthy water, nutrients, and carbon cycling—as evidenced by healthier crops, increased yields, improved soil test results, and vibrant microbial communities

- Biodiversity on land, in the air, and in the water (following improved biodiversity in the soil), including richer plant, bird, and insect populations

- Reduced soil erosion

- Reductions in water pollution—including contributions to harmful algal blooms—due to fewer chemical inputs

- Improvements to water-holding capacity in the soil

Personal and regional economic benefits

- Cost savings from reduced use of antibiotics and chemical fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides

- Greater financial security from diversified revenue streams

- The promotion of rural economic development with local employment and healthier food choices

Plantation Park Heights Urban Farm (PPHUF) hosts an event in Baltimore. Founded by a group of Caribbean American residents, PPHUF focuses on positive change for local young adults along with food production and distribution throughout the community.

Preston Keres/USDA FPAC

Community benefits

- Networks of growers who exchange information, learn from one another, and build community

- On-farm/on-ranch visits and networks of farmers’ markets that help farmers and ranchers build stronger relationships between consumers and their food

Mental and physical health benefits

- Many regenerative agriculture farmers and ranchers report feeling joy through their professions.

- The health of farmers, farmworkers, and downstream communities all benefit from reduced use of and exposure to harmful chemicals.

Regenerative agriculture techniques

There are many practices that fulfill a regenerative philosophy. Note that this list is not comprehensive, and not all regenerative growers use all of these practices.

- Cover cropping: The practice of planting crops in soil that would normally otherwise be bare after a cash crop is grown and harvested. By keeping living roots in the soil, cover crops reduce soil erosion, increase water retention, improve soil health, increase biodiversity, and more. They can be planted during harvest time or in between rows of permanent crops.

- Holistically managed grazing, also known as intensive rotational grazing: An Indigenous practice that mimics the way large animals moved in herds across grasslands. This method of grazing moves livestock between pastures on a regular basis to improve soil fertility and allow pasture grasses time to regrow.

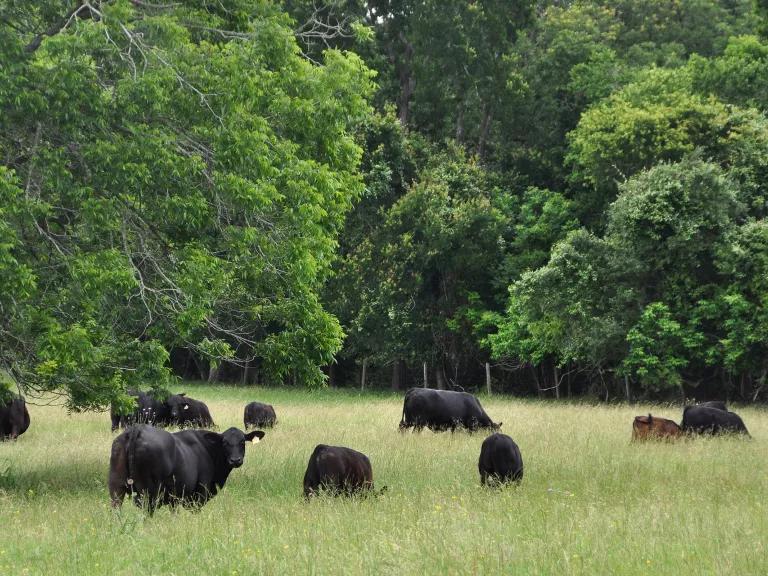

Cattle graze in a rotational pasture on a farm near La Grange, Texas.

Ron Nichols/USDA NRCS

- No-till farming: A technique that leaves the soil intact when planting rather than disturbing the soil through plowing.

A roller crimper is used to terminate cover crops so they can act as mulch in a no-till field on a farm in Evansville, Indiana.

Brandon O’Connor/NRCS

- Composting: The natural process of turning waste (from manure or food) into fertilizer.

Marvin Hayes, founder of Baltimore Compost Collective, holds fresh compost at the Filbert Street Community Garden in Baltimore.

Miriam Doan

- Reduced or no fossil fuel–based inputs, including pesticides: Building soil health and leveraging other natural systems to help manage pests and reduce the reliance on pesticides or other chemicals, regardless of whether a farmer decides to pursue organic certification.

Organic crops being tended at Soul Fire Farm in Petersburg, New York

Courtesy Soul Fire Farm

- Agroforestry: An Indigenous practice wherein growers mimic forest systems by integrating trees and shrubs into crop and animal systems.

Free-roaming Iberian pigs graze under oak trees at Encina Farms in Middletown, California.

Marissa Leshnov for NRDC

- Conservation buffers like hedgerows and riparian buffers: Areas of land populated with various plants to help manage specific environmental issues. Hedgerows are lines of shrubs or trees around farm fields that act as windbreaks and habitat for beneficial organisms. Riparian buffers are vegetated zones near streams that serve as habitat, protect water quality, and mitigate flooding.

A riparian buffer on farmland in Story County, Iowa

Lynn Betts/NRCS SWCS

Regenerative agriculture and climate change

Agriculture plays a significant role in contributing to climate change. Our food systems are also suffering enormous consequences from rising temperatures and increases in extreme weather events like droughts and floods.

The regenerative agriculture movement addresses the climate crisis with practices that sequester more carbon in the soil and help make farmland—and local communities—more resilient. In fact, farming and ranching can play an important part in natural climate solutions, as described below.

Improve soil health to mitigate climate change impacts

Soil is one of the earth’s greatest carbon sinks, thanks to photosynthesis and microbes. With proper care, soil can draw down 250 million metric tons of carbon dioxide–equivalent greenhouse gasses every year—and that’s just in the United States.

Abby Zlotnick shows the roots of a plant grown with regenerative practices on her farm, Juniper Farm, on leased public lands in Pitkin County, Colorado.

Jeremy Swanson for NRDC

Boost climate resilience

As flood, drought, and other extreme weather patterns become more frequent, farmers and ranchers are preparing their land to be more resilient. Healthy soils with high amounts of organic matter are able to absorb more water during a flood—to the benefit of the farmer and downstream communities—and even help maintain water security during a drought. Ranchers can also help prevent wildfires by grazing livestock to control brush.

NRDC and Incredible Beast Omnimedia teamed up with Nick Offerman to make sad soil smile again through climate-friendly regenerative farming. Tell your reps to take action to support healthy soil and a healthy planet: nrdc.org/soil.

Get fossil fuels out of agriculture

Our climate and health depend on ending our reliance on fossil fuel–based fertilizers and pesticides. Farmworkers, primarily Latino and immigrant workers, and their communities are in constant danger of exposure to these chemicals, putting them at risk of suffering acute and chronic health issues. More than 1.1 billion pounds of toxic pesticides were sold for use in 2018 in the state of California alone.

Leslie Wiser at Radical Family Farms in Sebastopol, California, where she and her wife, Sarah Deragon, grow fruits, vegetables, herbs, and flowers using regenerative techniques

Marissa Leshnov for NRDC

Reduce greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture

About 10 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions are attributed to farming and ranching, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, with the largest sources being livestock (such as cows), agricultural soils, and rice production. Some regenerative practices—including no-till farming, cover cropping, and rotational grazing—can decrease overall emissions from the agricultural sector.

Increase food production and preserve agricultural land

Considering that by 2050 we will need to feed a world population teetering on 10 billion, farms and ranches need to make even greater efforts to sustainably increase their productivity. Of course, as population increases, farmland is impacted in different ways in different regions. In some places, agricultural land is at risk of conversion to suburban and urban development. According to American Farmland Trust, 2,000 acres of agricultural land are converted by development every day in the United States. Supporting regenerative farms and ranches that embrace crop and animal diversity while boosting yields can help farms stay in business and prevent farmland from being lost to other uses.

Bloomfield Farm, a permanently protected 318-acre property, includes about 100 acres of restoration projects that reduce pollution in streams leading to the Corsica and Chester rivers in Queen Anne’s County, Maryland. The farm was purchased by the county with help from Eastern Shore Land Conservancy and offers recreational fields in addition to wildlife-viewing opportunities.

Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program, CC BY-NC 4.0

Protect and restore natural ecosystems

In other areas, mainly in tropical and subtropical regions, forests and grasslands are being converted for agricultural uses. Farmland isn’t just increasing in these places but it’s also shifting into more ecologically fragile areas, which are vital for healthy ecosystems. Land management efforts that complement regenerative agriculture practices would help to preserve these natural carbon sinks along with wildlife habitat and biodiversity. Abandoned or unproductive farm and ranch lands should be reforested or restored to natural ecosystems to minimize further land degradation and soil erosion.

How to support regenerative agriculture

Investing in regenerative agriculture

Despite all the benefits of regenerative agriculture, only a small percentage of U.S. farms have adopted regenerative practices—in part because U.S. farm policy does not prioritize them. But some states have started to encourage farmers, ranchers, and private landowners to adopt practices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In California, there are incentive programs like the Healthy Soils Initiative, the Biologically Integrated Farming Systems Program, and Sustainable Agriculture Lands Conservation Program. Since 2017, Iowa’s Department of Agriculture has been offering a $5-per-acre “good farmer discount” on crop insurance premiums to farmers who plant cover crops. These types of initiatives can serve as a model for other states looking to reward farmers for better management. Incentivizing these practices is only the first step toward transformative, systemic agricultural change. In addition, by directing technical assistance and financial resources to Black, Latino, and Indigenous farmers and other disadvantaged growers, we can begin to address historic injustices in our food system.

“Part of what’s needed now is a more holistic policy platform—one that pushes for transformational changes to our food and fiber system alongside the grassroots organizations, community leaders, artists, and revolutionary farmers we are learning from,” says Claire O’Connor, director of water and agriculture at NRDC.

Regenerative agriculture at home: what you can do

Whether you’re a farmer, a gardener, or a consumer, you can join the regenerative agriculture movement.

Daniel Cruz stocks organic plums at Kashiwase Farms’ stand at the Agricultural Institute of Marin’s (AIM) market in San Rafael, California.

Marissa Leshnov for NRDC

- Be a voice for soil: Demand proper stewardship of our land through regenerative agriculture. Talk to your neighbors and local policymakers. Support organizations that are trying to build better soil.

- Talk to a farmer or rancher: Knowing who grows your food, how they grow it, and where it’s grown is a crucial step toward building regenerative food systems and shortening our agricultural supply chain. The next time you’re at a grocery store or supermarket, ask the store owner what they know about the food they source. Connect with your local farmers at a farmers’ market or farm visit and ask them about their soil practices. Consider subscribing to a local Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) farm.

- Compost at home: Divert your household food waste from the landfill while closing the loop of our nutrient-and-soil cycle.

- Be a regenerative agriculture consumer: Know how your food is sourced and choose meat, dairy, and produce that are grown to help regenerate land. When dining out, opt for restaurants that source ingredients from regenerative farmers.

- Grow your own food: Follow regenerative agriculture techniques no matter what size your plot is. Feel empowered to start your own regenerative garden.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

In Planning for Climate Change, Native Americans Draw on the Past

Climate Change Is Already Driving Mass Migration Around the Globe

The Smart Seafood and Sustainable Fish Buying Guide