No Need to Reinvent the Forest

Forests have a major role to play in combating the climate crisis. However, this is not a problem we can solve by incentivizing more logging.

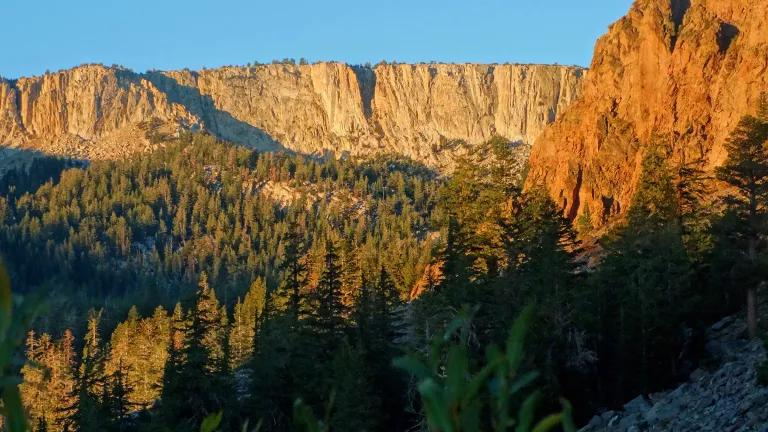

Giant sequoia trees in Redwood National Park, California

Carmen Martínez Torrón/Getty Images

Forests as a force for climate, biodiversity, and communities

In 2007, Richard Branson offered a $25 million prize for anyone who could create a device capable of removing lots of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. In response, Andy Kerr, an environmentalist and author, drew a picture of a tree and turned it in. He didn’t win, but Kerr had a point. Without forests, life as we know it would not be possible. In honor of International Day of Forests, it is important to underscore that our forests are the original innovators and remain the most cost-effective, highly evolved, and proven way to capture and store carbon.

Forests are some of our best allies in combatting climate change and are responsible for sequestering huge quantities of annual carbon emissions globally. Functional forest ecosystems are critical for addressing the climate emergency, protecting biodiversity, and safeguarding communities. Diverse, intact forests are uniquely well suited to mitigate pressing climate problems because they have adapted and evolved over millions of years to withstand periodic changes in climate. When preserved as high-integrity ecosystems, forests are more resilient to the perturbations associated with the current climate crisis. With climate change already causing serious impacts, we must remember that forests are not merely a commodity to be extracted and sold but are complex ecosystems that provide multiple life-supporting services.

Anthropogenic climate change is significantly altering natural forest processes, such as wildfires. However, as forests and trees mature, they develop a mosaic of characteristics that can help increase their resilience to wildfires and drought. Given that mature trees are often less likely to succumb to natural disturbance–related mortality, they can play an important role in continuing to sequester and store carbon as the rest of the ecosystem recovers. Functional, mature forests also provide relatively cool, shady microclimates for other plants and animals. These climate refugia will only become more important as climate change accelerates.

The benefits of a mature forest ecosystem extend beyond the forest itself and can help communities withstand the worst impacts of climate change. For example, as communities in the southern United States brace for storm seasons that are intensifying and becoming less predictable, communities laud intact wetland forests for their role in soaking up flood waters during periods of heavy rain. Protecting mature forests can provide a key buffer for communities against some of the worst effects of climate change.

Prioritization and values

Modern U.S. forest management retains roots in a colonialist approach that devalues Indigenous knowledge and stewardship practices on Indigenous People’s ancestral homelands. This approach—combined with the active erasure of Indigenous communities and their ways of living—often disrupts ecosystem functions that were maintained by cultural burning and other forms of traditional management. And it is actualized through management activities that are too often focused on extracting resources, such as timber and wood pellet biomass, despite the climate and community benefits that standing forests provide. This extraction, paired with decades of fire suppression, has hindered some forests’ natural climate resilience.

In the United States, logging has an outsize impact on forest carbon when compared to natural disturbances. Left alone, the carbon of dead or fallen large trees can persist in the forest for extremely long periods. These trees decay slowly, provide critical habitat, and eventually return important nutrients to the soil. In contrast, when trees are removed from the forest, they start to rapidly lose carbon.

The logging, manufacture, use, and decay of wood products emits stored carbon over a relatively short time. This is especially true of wood pellet biomass energy, where tree carbon is emitted almost instantly. However, national carbon accounting efforts often neglect logging-related emissions, overstate substitution benefits, and ignore the lost sequestration potential of mature, intact forests.

This is nothing new. The United States has yet to grapple with the role that the logging industry plays in the climate crisis; it insufficiently protects mature and old-growth forests across the landscape and fails to prevent our forests from being shipped overseas as wood pellet biomass for electricity.

Overlooking these emissions sources removes critical tools for solving the climate crisis. Further, replanting with saplings cannot meaningfully replace the loss of existing forests in the timeline necessary to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. Rather, we need a paradigm shift to ensure the long-term health of our forest ecosystems and communities.

Letting forests take the lead

The United States needs to re-center people and climate over profits when developing forest management plans. Below are our recommendations for innovative measures that would help to protect forest ecosystems, biodiversity, and our communities from the worst effects of climate change.

End support for forest biomass energy.

At a time when we need mature, diverse forests more than ever, we see forest degradation occurring at an alarming rate, with wood being shipped overseas to be burned for dirty biomass power. For a decade, wood pellet production mills have expanded across the Southeast, led by giants such as Enviva and Drax, to supply bioenergy-dependent regions like the United Kingdom, Europe, Japan, and South Korea. Now, as demand from these overseas markets grows, wood pellet producers are even eyeing the West Coast as their newest fiber basket. Using wood pellet biomass for energy increases logging and makes climate change worse. Infuriatingly, these practices are not only allowed but are being subsidized domestically and abroad—falsely peddled by the biomass industry as climate solutions.

The time is now to utilize energy sources that actually lower greenhouse gas emissions, are reliable, and cost-effective. Burning forest biomass is not a climate solution.

Protect mature and old-growth forests and trees.

Thinning or otherwise cutting down a tree in mature and old-growth stands can be motivated by legitimate ecological restoration needs. In such cases, there are often numerous end uses within the forest system that could aid in restoration, preserving the internal functioning of the ecosystem. This could include leaving downed logs on the forest floor as habitat or relocating logs for use in streamside restoration. Significant opportunities exist for creative, ecologically oriented thinking when it comes to managing mature and old-growth forests.

It is when restoration management within mature and old-growth stands results in the commercial sale of timber that we must be cautious of economic motivations compromising the intended ecological outcome. The danger lies in both the carbon emitted from the removal, transportation, and processing of the wood, and in the opportunity for restoration to be used as a cover for ecologically inappropriate and harmful logging projects.

The Biden administration has recently taken steps to protect the remaining old-growth forests on federal lands. This, along with significant public support, is beginning to push the Forest Service in the right direction with stricter guardrails on cutting and selling our oldest trees and stands. Unfortunately, there is very little old growth left. To fully realize the benefits of our oldest forests, mature trees must be allowed to age.

Increase support for home hardening measures to protect communities.

People living in fire-prone areas are justifiably worried, and more needs to be done to support them directly. Research shows that logging big trees does not reduce fire spread or severity and, in fact, can make it worse because of an increased prevalence of smaller fuels. Weather is often the primary determinant of wildfire severity.

Federal agencies collectively need to be proactive about preventing loss of life and damage to property. These measures should involve far more funding for proactive preparations like home hardening, eliminating pinholes in structures and homes (most homes are damaged because an ember enters the home through an unsealed opening), and emergency preparation for community resources and evacuation.

Forests are nature’s innovator

Forests are nature’s original innovator in the fight against climate change. Most people know that burning fossil fuels is the primary anthropogenic cause of climate change. We must end our global dependence on fossil fuels and address emissions from other sources like logging while also removing the vast amounts of carbon pollution we have already emitted. Terrestrially, there is no better carbon-capture technology than forests. There is little recognition by land managers about the need to protect our forests to mitigate climate change, but the urgency of the climate crisis demands that we see forest defense as climate defense. On this International Day of Forests, we celebrate the critical role that forests play in addressing the climate emergency, protecting biodiversity, and safeguarding communities. The best innovator we have—the most highly evolved, tried, and true—is our forests.