Reports of Sickening Water Conditions at Pontiac, Illinois Prison

People imprisoned in Pontiac report using makeshift filters to protect themselves from water that is often described as oily, swampy, and brown or black.

A cell in the West House of Pontiac Correctional Center in Illinois.

“When I first started paying attention to the black stuff floating in my cup other inmates told me to rip a piece of my bed cotton to use as a filter,” says one of the nearly 600 individuals incarcerated at Illinois’s Pontiac Correctional Center.

“We use cotton from our mattress as a filter that turns black, and got green stains on it too,” writes another.

“If you do not use a cotton filter from your mattress to drink this water,” reports a third, “you will develop some type of infection or disease.”

Much like the surveys described in our blog post last year at Vienna Correctional Center, reports out of Pontiac paint a deeply disturbing picture of environmental conditions at Illinois prisons.

Over the past 50 years, communities in the United States have witnessed a dramatic increase in the practice of imprisonment. The rate of those caged in federal or state prisons has approximately quadrupled since the early 1970s, when backlash to the civil rights movement marked a starting point for radical expansion to a highly racialized carceral state.

One consequence of this carceral boom is the inability or unwillingness of states to guarantee humane conditions for the people they condemn to prison—conditions such as safe, clean drinking water. Though incarceration may inherently entail a deprivation of rights and liberties, the right to clean water does not stop at the prison wall. No one is sentenced to drink poisoned water.

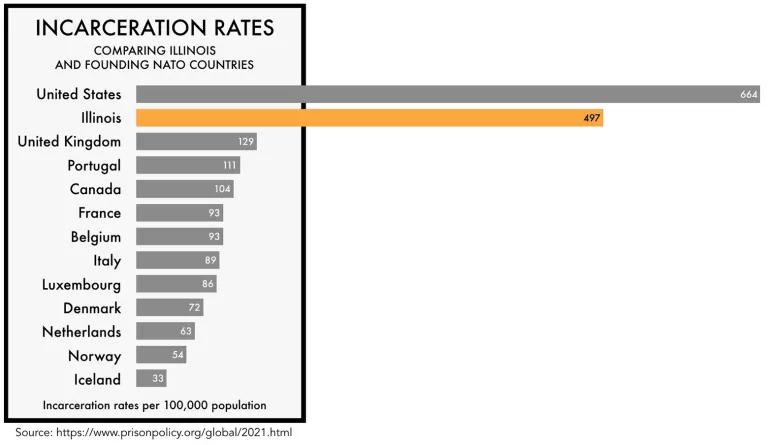

Illinois is no exception to the national patterns of imprisonment. As a demonstrative comparison, the state's overall incarceration rate is nearly four times higher than the United Kingdom’s. Furthermore, the impacts of incarceration fall disproportionately on people of color: Illinois’s incarcerated population is majority Black, even though only about 15 percent of the state’s overall population is Black.

Incarceration Rates: Comparing Illinois and Founding NATO Countries.

One way to think of prisons is within the framing of environmental justice communities. As with prisons in the rest of the country, Illinois’s troubling incarceration statistics are paired with serious concerns regarding the environmental conditions experienced within prisons, such as poor water quality. For this reason, in 2023, NRDC partnered with Uptown People’s Law Center, the Coalition to Decarcerate IL, and other grassroots organizations to survey those confined at Pontiac about the water they are forced to drink.

Pontiac, which first opened more than 150 years ago in Central Illinois, is notorious for its general disrepair. A report prepared for the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) last year found that Pontiac was “approaching an 'Inoperable' rating” and “was never intended to be a rehabilitative, supportive environment.” The same report highlighted the need to replace plumbing fixtures and faucets, and ultimately recommended reducing Pontiac’s capacity “[g]iven its age, outdated/inefficient design, extensive physical plant needs, high cost to operate, and difficulty in recruiting and retaining staff.”

A total of 170 individuals responded to the survey. An overwhelming majority of all respondents (96 percent) expressed concern about the water quality at Pontiac. A similar number (88 percent) reported that the water had an unusual odor, and dozens of respondents described the taste as being “swampy” or like “sewage.” Despite these concerns, more than three-quarters of respondents reported using the prison’s tap water. “What can I do?” wrote one respondent. “Everyone can’t afford to buy water from the commissary.”

The water at Pontiac is visibly contaminated as well. For years, those incarcerated at Pontiac have improvised their own water filters by using bedding material to catch the black, oily substance that comes out with their tap water. Numerous individuals—some of whom are quoted at the beginning of this piece—referenced these filters in their survey responses.

Indeed, beyond the surveys, we have confirmation of this practice from water testing reports prepared by the prison’s own third-party contractor. In a 2022 report, for example, an inspector noted to IDOC: “Inmate had mattres [sic] material over sink spout as a filter. Sampled with mattress material dripping into sample bottle.”

All in all, 66 respondents reported that their water was dark brown or black, and 75 respondents reported an oily substance in the water. Dozens of others reported water that was yellow, orange, red, or brown; and dozens also reported that it contained slime or visible particles. Over a third of respondents reported that they’d filed a grievance about the tap water to notify Pontiac officials of their concerns, but most noted that the grievances went unanswered.

The health and psychological impact of being forced to consume unclean water for weeks, months, or years on end cannot be understated. Most respondents reported having abdominal cramps, diarrhea, and headaches. Alarmingly, over 50 respondents reported having blood in their stool. These symptoms were also attached to diagnoses; more than 60 respondents reported being diagnosed with ear, nose, or throat infections while at Pontiac, and dozens of others reported stomach ulcers and urinary tract infections.

Despite these widespread health issues, individuals incarcerated at Pontiac report that their health care providers ignore their pain: “I've been complaining and have been seen, but nothing is ever done.” Many respondents explicitly link their health symptoms to their water consumption. “I and others have seen the issues decline when we've gotten bottled water,” one wrote.

The risk of avoiding water altogether presents an additional endangerment to human health. In addition to the numerous health concerns that are inherently implicated by dehydration, the lack of water also reduces a person's ability to withstand extreme heat. In facilities without cooling systems, the only way to regulate body temperature is through sweating—a water-intensive process. Although this issue is more commonly recognized as a pervasive and lethal problem in hotter southern states like Texas, death from hyperthermia (overheating) is not unheard of in IDOC prisons.

Our changing climate means that heat waves will only become a more frequent challenge for northern states in the future. Researchers have found that increased exposure to extreme heat days is associated with a measurable increase in overall deaths in U.S. state and private prisons—and may also align with an increase in suicides.

Pontiac represents one of countless prisons where conditions are untenable. As our team wrote with respect to surveys at Vienna Correctional Center: “In Illinois, sentencing a person to prison effectively means sentencing them to years, decades, or a lifetime of foul and sickening water. Advancing environmental justice means demanding that these practices end.”

When Illinois sentences someone to prison, that person loses their physical freedom—they do not have any alternative to the water that the state provides to them. Nor do they have the right to sample their water themselves. Their access to news reporters is highly limited; they cannot vote for officials who will come to see the water with their own eyes and legislate fixes. This is true of every prison in the country. Too often, the people confined to live behind prison walls are abandoned by those outside.

But where access to the necessities of life is controlled entirely by the state, the duty to ensure humane conditions is arguably at its highest. Environmental challenges are on the rise everywhere; environmental justice means rejecting a framework that allows burdens to fall on those who are most marginalized.

To learn more about the work against inhumane water conditions in Illinois prisons, follow Coalition to Decarcerate Illinois (Website; Instagram) and Uptown People’s Law Center (Website; Instagram).

This blog provides general information, not legal advice. If you need legal help, please consult a lawyer in your state.