A Simple Way to Fix the Gas Tax Forever

State policy is inappropriately favoring many gas-powered cars over zero-emission vehicles.

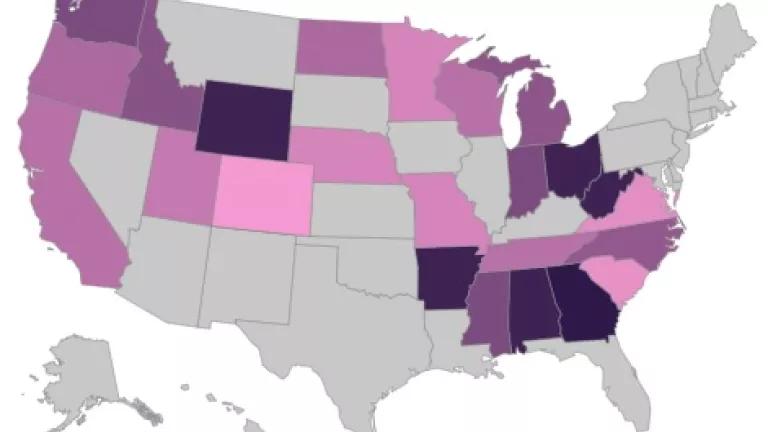

States Imposing Special Annual Fees on Electric Vehicles (darker color indicates more expensive fee)

Twenty-four states now impose special fees on electric vehicles (EVs) meant to make up for the fact EVs don’t pay gas taxes (despite the fact they often pay local taxes on electricity). The average state EV fee of $128 per year is more than twice what someone driving an efficient gasoline car pays annually in state gas taxes. That means state policy is inappropriately favoring many gas-powered cars over zero-emission vehicles. Such fees can significantly erode or completely erase the fuel cost savings that motivate consumers to buy EVs and they hit low- and moderate-income households the hardest.

Fees on EVs also fail to address the real issues eroding transportation funding. Instead of imposing unjustifiable high fees on the cleanest vehicles on the road, we should fix the gas tax to address the actual sources of transportation revenue shortfalls and tax EVs as if they drove on gasoline.

The transportation funding system is bankrupt. Our roads and bridges are falling apart, and our public transit systems and bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure systems are dramatically underfunded. But the following two simple steps would forever solve the problem without perpetuating our dependence on fossil fuels.

Step 1: Index the Gas Tax to Inflation and Total Fuel Consumption

Despite the attention they’re getting, EVs are a rounding error in terms of sources of transportation funding losses. In fact, even if the EV sales increased ten-fold by 2025, they would still account for only about 3 percent of cumulative lost revenues. Inflation is the biggest culprit. Because Congress hasn’t raised the gas tax to keep pace with inflation in over 25 years, today’s federal gas tax collects one-seventh the amount of real revenue it did in 1950. In most states, the story is the same, but a few states have wisely indexed their fuel taxes to inflation, resulting in automatic annual adjustments that prevent crippling cumulative loses. Any effort to fix federal or state fuel taxes should include the simple fix of indexing to keep pace with inflation.

While small relative to inflation, improved fuel economy and slower growth in vehicle miles travelled (VMT), are also sources of transportation funding revenue losses. In response, some have suggested we should ditch the gas tax and replace it with VMT fees, but a simple VMT fee that assesses the same cent-per-mile fee on all vehicles ignores the fact that heavier vehicles (which use more fuel) are responsible for the vast majority of damage to the roads and it removes the incentive for people to buy more efficient vehicles and to drive them more efficiently. It is estimated that replacing the federal gas tax with a simple VMT fee would result in 45 million tonnes more of global warming pollution annually. To address these issues, other researchers have suggested varying VMT fees to account for vehicle efficiency and/or weight. But that’s like taking a solution already in-hand and breaking it into problems. Fuel taxes already encourage efficiency and discourage weight (because it takes more fuel to move a heavier vehicle).

Given the vast majority of the fleet continues to use conventional fuels, the current fuel tax system makes sense, especially because it is incredibly efficient from an administrative point-of-view; it costs almost nothing to collect and there is very little evasion. In contrast, VMT fees raise various administrative issues, including privacy and cost issues that have proven difficult to overcome. An ideal VMT policy would address weight or vehicle efficiency (replicating the incentives already inherent in the gas tax), but that could introduce additional adminstrative challenges. Until such issues are resolved, place-based congestion fees are a strong alternative to advance the social goods that attract many to VMT fees.

Rather than ditching the gas tax to address the fact vehicles are using less fuel, we should simply index the gas tax to total fuel consumption. In combination with the adjustments to keep pace with inflation, this would result in small annual increases that prevent big cumulative losses. For example, if the rate of inflation is 1 percent and total fuel consumption drops by 1 percent over a year, fuel taxes would automatically increase by 2 percent to make up for the difference the next year. Or if the rate of inflation is 1 percent and total fuel consumption increases by 2 percent, fuel taxes would automatically decrease by 1 percent to avoid over-collecting revenue. Such incremental adjustments would go unnoticed because they would be in the noise relative to the volatility of the global oil market.

We know this could work because it’s basically already been done. Many states already index their fuel taxes to inflation, and, decades ago, utility regulators began adopting “revenue decoupling” mechanisms that automatically adjust the price of electricity and natural gas up or down to ensure regulated utilities recover no more or nor less than their authorized revenue requirements. Those mechanisms ensure that utilities are agnostic to the volume of electricity and natural gas sold so their financial health is not being undermined when customers adopt energy efficient appliances, lowering total bills and reducing pollution. It’s time to decouple the gas tax so that the financial health of our transportation system does not require perpetuating our reliance on fossil fuels.

Indexing the gas tax to inflation and total fuel consumption would forever plug the two biggest holes in the leaking transportation funding bucket. All that’s left to do is patch the tiny hole caused by EV adoption before it becomes a real problem, which brings us to Step 2.

Step 2: Tax EVs as if They Drove on Gasoline

EVs are not a significant source of transportation funding shortfalls, nor are they expected to be anytime soon. As noted above, even if EVs sales increased ten-fold by 2025, they would still account for about 3 percent of cumulative transportation funding revenue losses from 2010.

And EVs today are generally subject to local utility taxes that pay for local services, including the maintenance of local roads where a third of all VMT occur. So, it’s a false premise that EVs not subject to EV-specific fees fail to pay for road maintenance or other important services.

But this hasn’t stopped 24 state legislatures from imposing onerous fees that generally exceed what efficient gasoline vehicles pay annually. The average of those annual state fees on pure battery electric vehicles is $128, which is more than twice the $62 a Toyota Prius Eco driver would pay annually in average state gas taxes.

You might ask: “Why not compare the EV to the average gasoline vehicle?” But taxing EVs at an annual rate equal to the average vehicle would favor efficient gasoline vehicles over zero-emission electric vehicles. Lawmakers should be technology-neutral, encouraging efficiency across the board. It makes no sense to skew the market toward efficient gasoline vehicles and away from more efficient and less polluting electric vehicles.

Similarly, many states fail to distinguish between pure battery electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles that can drive on both electricity and gasoline, which means plug-in hybrid drivers subject to EV fees often get taxed twice, once at the pump and once at the DMV.

To reduce America’s dependence on oil and to address the climate crisis, we need to rapidly accelerate the EV market now. The EV fees that are the law of the land in 24 states will hamper that effort. Researchers from the UC Davis Institute of Transportation Studies estimate California’s $100 annual fee on EVs will reduce EV sales by 10-20 percent in the short run. That might seem like a big impact when you consider $100 per year is still relatively small compared to the total cost of car ownership, but numerous surveys reveal the single biggest motivator of EV purchase decisions is a desire to save money on fuel. A typical EV driver will save a $200 in fuel relative to a Prius Eco driver (the comparison is apt because many EV drivers are former hybrid drivers). As in, the EV fees adopted across the nation that range from $50-$214 can significantly erode or completely erase the fuel cost savings that motivate EV purchases.

Such fees will hit also low- and moderate-income households the hardest, households who already spend a disproportionate share of their income on transportation expenses and who would most benefit from a switch to EVs. Unlike typical vehicle registration fees that go down as the value of the vehicle declines, these constant and regressive EV fees will stick with the vehicles for life. While annual EV fees may not discourage many new vehicle buyers, they will likely be a significant impediment for many low-and moderate-income households. They already spend a disproportionate share of their income on transportation; the last thing they need is to get hit with a $50-200 annual fee because they choose to invest in vehicles that improve local air quality.

Instead of imposing fees that are twice what drivers of efficient gasoline vehicles pay and that will hit low-income households hardest, we should tax EVs as if they drove on gasoline by assessing annual fees based on the miles-per-gallon-equivalent rating of the EV in question (a number that is readily available from www.fueleconomy.gov), the gas tax that would otherwise apply, and the typical number of miles a car drives annually. Taking Wisconsin as an example, that would mean someone driving a Chevrolet Bolt EV would pay $33 annually, retaining the appropriate incentive inherent in the gas tax for people to buy more efficient vehicles and doing so in a way that doesn’t favor one efficiency technology over the other.

Policy-makers looking for desperately needed revenue to fix our crumbling transportation infrastructure may initially dismiss a $33 annual fee as being too low, but if they also index fuel taxes to inflation and total fuel consumption (see Step 1), the annual fees levied on EVs would naturally increase over time, ensuring that transportation funding remained stable. Even if the entire U.S. vehicle fleet was electrified, the total amount of revenue collected would remain constant.

Taking both steps together would forever solve the transportation funding crisis and would do so in a way that doesn’t keep America hooked on oil.