Why Build a Seawall When You Can Plant Some Grass?

As the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers considers including “living shorelines” among its preferred erosion controls, Alabama is already leading the way to healthier coasts.

One of three experimentally restored marshes in Alabama's Safe Harbor canals about one and a half years after completion

Looking at the foot of Alabama on a map, you wouldn’t think its shoreline extended more than 600 miles. But the nooks and crannies of the state’s jagged coast are filled with all kinds of inlets, tidal bays, and bayous. And like elsewhere on the Gulf of Mexico, erosion is a serious problem.

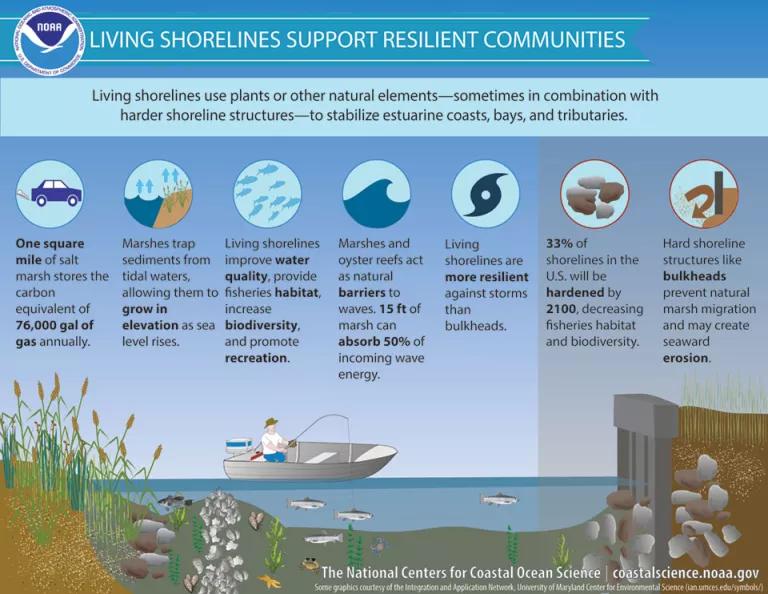

With pressures like climate change, population growth, and coastal development butting up against the wetlands of the Gulf and the Atlantic, there’s a lot at stake. (Louisiana alone loses a football field’s worth of land to the sea every hour.) Bulkheads, seawalls, and riprap revetments―barricades made from materials like sandbags, rocks, wood, or cement―are common strategies to keep land from washing away. But in Safe Harbor—an abandoned campground near Fairhope, Alabama, that is now part of the Weeks Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve—they’ve taken a softer approach: a “living shoreline.”

Safe Harbor’s system of deep canals—dredged more than 60 years ago to give campers direct access to Fish River and Weeks Bay—would better serve the area as marshes, but the steep banks prevent marsh plants from thriving. Marsh vegetation could help filter pollution, reduce erosion, and create a boggy nursery for shrimp, crabs, and other intertidal creatures.

Researchers installing weirs to simulate sea-level rise in the restored marsh to measure how successful the marshes will be in the future

So in 2012, scientists began an experiment. In hopes of kick-starting a fringing marsh along the canals, they trudged into the brackish water to plant black needlerush, a hardy plant with long, sturdy stems and an extensive root system. They also tied coconut coir logs, made from shredded coconut husk, into long, haylike rolls and dug them into the banks to hold sediment in place. Then time, water, and sunlight went to work. Today, a thicket of grasses growing along a gentle incline rims the canals.

“Living shorelines are important and essential for restoring and maintaining healthy coastal areas,” says Eric Sparks, a coastal ecologist with the Mississippi State University Extension Servicemarine biologist and the Mississippi–Alabama Sea Grant Consortium, a program managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “If a living shoreline is put in an area that’s suitable, there’s barely any upkeep involved,” says Sparks, who helped plant and monitor the Safe Harbor project.

About 14 percent of the U.S. coastline is “armored” with bulkheads, seawalls, and the like, and while those can be effective shields against strong waves, their applications don’t hold water in areas with lower wave energy, such as marshes and bays. In fact, bulkheads often increase erosion at the base of their walls and cause attrition elsewhere as they reflect oncoming waves and direct them down the beach. They also happen to be expensive, prone to cracking, and detrimental to nearshore habitats, diminishing their ability to support plant and animal life.

Living shorelines, which can include wetland plants, oyster reefs, sand, and stone, have started popping up along the coasts of North Carolina, Chesapeake Bay, Mobile Bay, and Puget Sound, but their popularity may get a big boost soon. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is in the process of updating its permits for certain wetland activities that fall under the federal Clean Water Act and the Harbors and Rivers Act. Creating a living shoreline is on the list. The new permit would serve as an alternative to the current option for shoreline stabilization called Nationwide Permit 13, which prioritizes bulkheads.

“Until now the Corps has been incentivizing structures to be put in that are harmful to wetlands,” says Rachel Gittman, a postdoctoral research associate at Northeastern University’s Marine Science Center. Now the Corps is trying “to make it an even playing field so someone who wants to make the environmental choice can.”

For the past few years, Gittman has been comparing natural buffers with “traditional shoreline-hardening” approaches in North Carolina. So far, she’s found that living shorelines provide better erosion protection during category 1 hurricanes than bulkheads and create healthier environments for juvenile fish and crustaceans than seawalls, which, on average, have 23 percent less biodiversity and 45 percent fewer organisms.

Still, getting the OK to build bulkheads and walls is much easier in most places around the country. The exceptions are Alabama and Mississippi. Thanks to progressive administrative changes within the Army Corps’s Mobile District earlier this decade, qualifying property owners have been able to construct living shorelines without having to obtain special permits through the Army Corps, typically a very lengthy process.

Of course, having an environmentally superior option doesn’t necessarily mean people will choose it. That’s why groups like the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) are petitioning the Army Corps to retire Permit 13 for bulkheads. “What they need to do is structure the regulatory process so living shorelines are viewed as the preferred technique for addressing erosion,” says Bill Sapp, an attorney for the SELC who specializes in wetland and coastal issues. Permits for bulkheads would be available only when appropriate―for instance, when shielding beach areas from powerful waves.

But first the living shorelines permit needs to get on the books nationwide. If approved by the Army Corps next March, the permit would help create some regulatory unity, says Niki Pace of the Louisiana Sea Grant Law & Policy Program at Louisiana State University. It also would give some overdue cred to more natural methods of erosion control. And that could help move things along in states that have yet to take a softer, but often more effective, approach to coastline management. With quite a few restoration projects under its belt already, Alabama can show them how it’s done.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

In Planning for Climate Change, Native Americans Draw on the Past

California’s Climate Whiplash

Colorado River Basin Tribes Address a Historic Drought—and Their Water Rights—Head-On