Why the EPA Needs Another William Ruckelshaus (1932–2019)

The agency’s first administrator built the EPA from scratch—and established the nonpartisan, antipolluter culture that the Trump administration has all but abandoned.

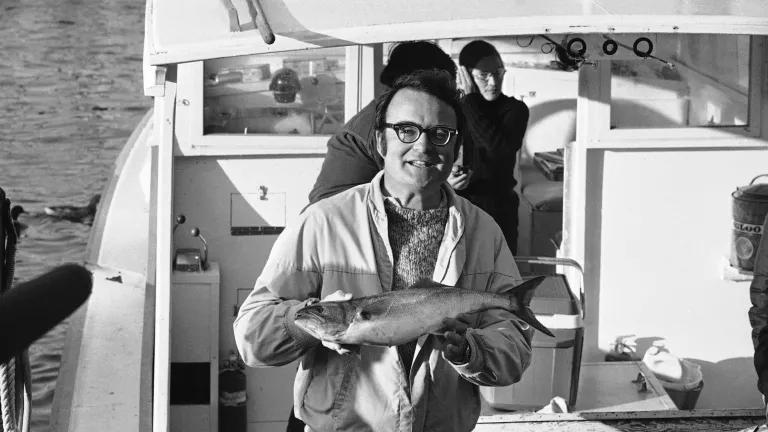

William D. Ruckelshaus on a fishing trip to the Chesapeake Bay in 1973

William Ruckelshaus passed away a few weeks ago at the age of 87. If you’re under 65, you can be forgiven for not knowing his name or appreciating his significance. Many of those who do remember Ruckelshaus probably know him as the deputy attorney general under President Richard Nixon who chose to resign one fateful Saturday night rather than carry out his boss’s order to fire the special prosecutor during the Watergate scandal—making him one of the few figures to survive that sordid episode with their honor and integrity fully intact.

But before he was deputy attorney general, Ruckelshaus held another position in the Nixon administration as the first head of the newly formed U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which came into being in 1970. And while his role in Watergate has earned him a place in the history books, his energetic leadership of the EPA in its earliest days is his true legacy. Ruckelshaus conceived the organizational framework for the agency, shaped its mission, and made valuable contributions to our air and water safety. But above all, his tenure as EPA administrator stands as a wistful reminder that trusting in science, going after polluters, and protecting the environment were once considered by most Americans to be uncontroversial and nonpartisan.

The EPA emerged, in part, as a result of mounting public concern over pollution and the sense that that the problem would only get worse if industry practices continued to go unchecked. By 1970, choking smog was a defining trait of life in Southern California, and it had been for decades. In 1969, the year before the EPA was established, a massive oil spill dumped three million gallons of crude into the waters off Santa Barbara, California, resulting in a 35-mile-long, wildlife-suffocating oil slick. That same year, stunned Clevelanders bore witness to the burning of the Cuyahoga River. The waterway had become so suffused with oil and combustible chemicals that it was literally flammable.

Ruckelshaus, who was only 38 at the time he started at the EPA, immediately began informing industrial polluters and local officials that the days of unregulated dumping and lax enforcement were over. To the mayors of Atlanta, Detroit, and Cleveland he issued an ultimatum: comply with water-quality rules within 180 days, or face legal consequences. Cities that were ignoring clean-air standards were given five-year deadlines to come into compliance. He took on U.S. Steel and other water polluters, requiring them to disclose information about what they were dumping into American waterways in the course of doing business. In his most visible act as EPA chief, Ruckelshaus set rules in motion that led to the eventual banning of DDT.

Later in his life, Ruckelshaus was asked to run the EPA again—at the behest of another Republican president. When Ronald Reagan realized that he needed to restore public faith in the agency after the brief, scandal-ridden tenure of his first pick, Anne Gorsuch, he knew exactly whom to call. During his second stint at the agency, Ruckelshaus provided important leadership on rules pertaining to asbestos, leaded gasoline, and the ozone layer. Even in retirement he continued working on behalf of the environment: well into his eighties, Ruckelshaus was publicly criticizing Donald Trump’s EPA for blithely tossing the Clean Water Rule aside and acquiescing to mining interests in Alaska’s Bristol Bay.

In a 1991 interview—one that’s very much worth reading if you’re interested in the context for the environmental movement that blossomed in the 1960s and 1970s—Ruckelshaus emphasized the importance of public engagement in securing environmental protections. The EPA, he said, “never would have been established had it not been for public demand. That I am absolutely certain of.” Public demand was essential, he said, “because the forces of the economy and the impact on people’s livelihood are so much more automatic and endemic. Absent some countervailing public pressure for the environment, nothing much will happen.”

Today, nearly 50 years after the EPA’s founding, climate change is the most pressing issue of our era, and the one issue with the potential to unite Americans—of all beliefs, and from all backgrounds—in demanding action. I’m typing these words just one day after Time magazine named Greta Thunberg its 2019 Person of the Year, in recognition of the 16-year-old climate activist’s role in shaping an international, youth-led climate movement that has stimulated a burgeoning of climate consciousness in the United States and around the world. Now more than ever, Americans need and deserve an EPA that is responsive to the overwhelming public demand for an end to our nation’s addiction to fossil fuels that pollute the air we breathe and threaten to disrupt the natural systems on which human life depends.

Under President Trump we have the opposite, of course. Even as its dedicated staff stoically soldiers on, the current leadership at the EPA dishonors the memory and legacy of William Ruckelshaus and of the vast majority of administrators—Republican and Democrat alike—who came after him. All of them understood and believed in their mission of protecting public health by holding polluters accountable. Though Ruckelshaus has left us, we should hold his example in our minds as we push for the EPA to survive its own sordid episode with its honor and integrity intact.

This article was originally published on onEarth, which is no longer in publication. onEarth was founded in 1979 as the Amicus Journal, an independent magazine of thought and opinion on the environment. All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of NRDC. This article is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the article was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the article cannot be edited (beyond simple things such grammar); you can’t resell the article in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select articles individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our articles.

As Trump Moves to Expand Offshore Drilling, He Proposes Shrinking Safety Protections. What Could Go Wrong?

How to Become a Community Scientist

A Leader to Meet This Moment