RI Report Mistakenly Recommends Insufficient Action

This blog was co-authored with Matt Rusteika of Acadia Center.

Rhode Island is usually a clean energy leader. It often ranks among the highest-achieving states in energy efficiency, being among the top three in the last two years. And the state has already taken important initial steps to eliminate carbon emissions from its buildings. Unfortunately, a recent report on how Rhode Island should transform its heating industry could derail this momentum and delay action at a crucial moment in the fight against the climate crisis.

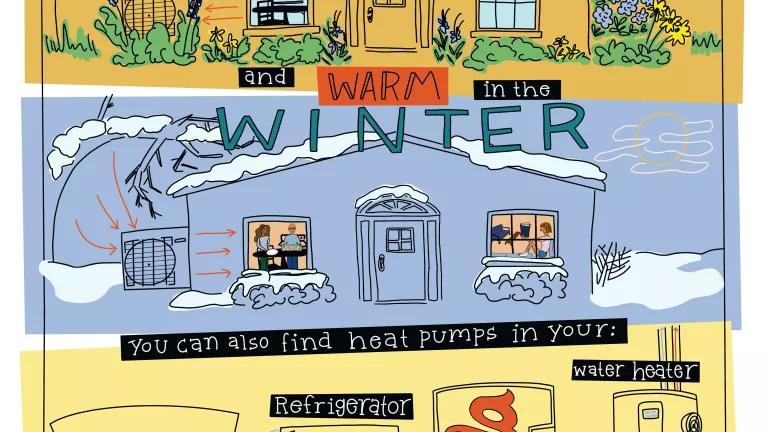

That report, conducted for the Rhode Island Office of Energy Resources, fails to recommend the necessarily aggressive adoption of highly efficient electric heat pumps as a crucial tool for reducing carbon emissions. This recommendation is based on two incorrect assumptions about whether the most efficient heating technology on the market today—electric heat pumps—is the best option for Rhode Island homes and businesses. The pace and scale of heat pump adoption recommended in this report is insufficient for Rhode Island and the report’s lacking recommendations should not be used to delay or slow action in other northeastern states.

Buildings emit 27 percent of Rhode Island’s carbon emissions. Eliminating them is necessary to meet the state’s long-term climate goals. Doing so by replacing gas use with clean electricity will lead to healthier, more comfortable homes and places of work for all. This is known as building electrification and is a key “decarbonization” strategy.

The Rhode Island report makes several useful recommendations for advancing these goals, such as investing in energy efficiency for buildings and taking advantage of natural opportunities to install efficient, clean electric appliances in buildings as older equipment breaks down. It also recommends that the state develop a gas transition plan to prepare for a future where fossil gas is no longer in use. Both of these recommendations will help minimize the cost of decarbonizing our buildings.

Unfortunately, the report’s central recommendation is that, over the next 10 years, Rhode Island should not work to advance specific solutions to eliminate carbon emissions from buildings. In other words, the report asks Rhode Islanders to spend more time studying and equivocating about how to decarbonize rather than doing the responsible thing by acting now. Delaying action for this long would certainly drive up the cost of meeting the state’s 2050 climate goals.

Inaction today is dangerous, not to mention how risky it would be over the next 10 years. A decade of slow movement would eat up one-third of the time we have left to eliminate enough carbon to curb the catastrophic effects of climate change.

Two Incorrect Assumptions Led to Misguided Recommendation

The recommendation to “wait and see” is based on two faulty assumptions:

- The analysis behind the report assumes that air source heat pumps—one of the breakthrough appliances that allow consumers to heat their homes efficiently with electricity that is increasingly generated from emissions-free renewable resources—perform no better than outdated electric resistance space heaters at very cold temperatures (below five degrees Fahrenheit). The effect of this assumption is over emphasized in the report, since heat pumps designed specifically for cold climates have an average annual efficiency that is more than 3 times the efficiency of modern furnaces even when accounting for the coldest days and nights of the year. Rhode Island weather rarely drops below five degrees. It makes little sense to build an analysis around that extreme case when impacts on the power system can be addressed with a comprehensive electric use management strategy and minimal fossil fuel backup during the few very cold hours each year.

- The analysis also assumes that installation costs for heat pump technologies will drop by just 2 percent each year. That’s a very conservative assumption, given that experts were already predicting a 20 percent decline in cost by 2030 in 2017. The best way to for Rhode Island to accelerate this reduction in heat pump installation costs is to enact statewide electrification targets and other concrete policy commitments, but the report declines to recommend these actions. Other promising technologies have experienced much more dramatic cost decreases when supported by ambitious policies. For example, the cost of rooftop solar power fell by 89 percent over the last 11 years. If Rhode Island commits to efficient electrification of buildings, it has the power to help drive further cost decreases, if it doesn’t, costs may remain higher than they otherwise could be. The analysis fails to capture this important opportunity.

If the Rhode Island report had gotten these two assumptions right, it likely would have arrived at the same conclusion that other analyses have reached: clean, efficient electrification can be the lowest cost pathway to eliminate carbon from buildings, and installing heat pump space and water heaters is an essential part of any efficient electrification plan.

Buildings and the equipment inside them are designed to operate for a long time. What we build and install now will continue to be in use through 2030 and likely 2050. That is why we must embrace the technologies that are already proven and available on the market—clean, efficient electric appliances—as the central solution for removing climate- and health-harming carbon emissions from our homes and workplaces.