Glacial risks in Chile will be addressed by international scientists at an upcoming symposium

In early September, an international symposium in Chile will address a fascinating and increasingly important topic in global climate change: GLOFs.

It is certainly not the prettiest acronym, but “GLOF” stands for glacial lake outburst flood – a mouthful of a term in its own right. (Equally difficult to pronounce is the Icelandic term for the same thing: jökulhlaup.) To describe this phenomenon in simple terms, this is a type of flood that occurs when water in a glacial lake has been blocked from flowing down a river by an obstacle – usually a glacier or moraine. The water increasingly builds up behind that obstacle until it can no longer be held back, at which point the water bursts through or over the obstacle and down the entire river in a sudden flood.

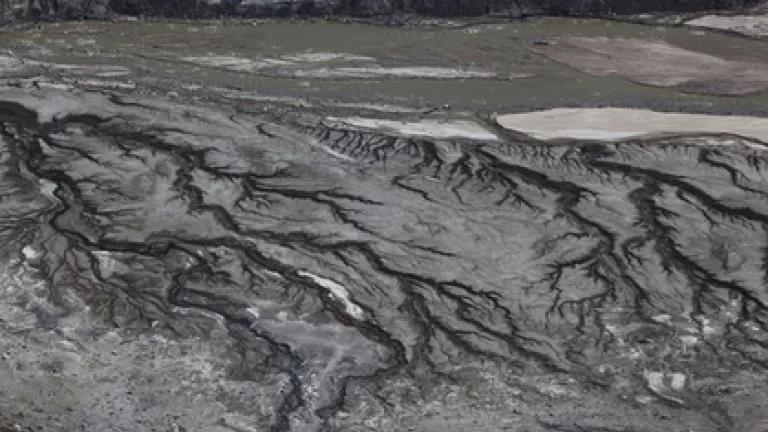

Lake Cachet One in Chile’s Patagonia, completely drained after a GLOF - photo courtesy of Daniel Beltra, The International League of Conservation Photographers and the Patagonia Foundation

These floods have occurred all over the world and throughout history. However, in recent years they have happened more frequently in the glacial areas that are particularly susceptible to warming temperatures, such as the Himalayas, Greenland, and Chile’s Patagonia. Warmer temperatures are melting the glaciers in these areas more quickly than ever before, speeding up the rate at which water in the glacial lakes builds up behind the obstacles, and therefore also speeding up the rate at which the glacial water bursts and floods the rivers.

For example, in Chilean Patagonia, the Colonia / Baker river system had not seen a single GLOF in 40 years, the last recorded event occurring in the early 1960s. Since 2008, however, this watershed has had six GLOFs: April, October and December 2008; March and September 2009; and January 2010. The flood in April 2008 was so strong that it destroyed the gauging station, and as a result authorities do not know exactly what the peak flow of that GLOF was. These events can be unpredictable, powerful and destructive, and they pose serious threats to the infrastructure and populations nearby. In a previous blog, I described some of the GLOF damage I witnessed on the Baker River.

a tree deposited on top of an enormous rock by a GLOF on the Baker River

The changing geology of areas close to mountains, glaciers and vast ice-fields, such as the Northern and Southern Patagonia Ice-fields in Chile, also creates a larger concern about the instability of the water and sediment there. These issues are important variables to consider when municipalities plan road construction and population growth. For example, the April 2008 GLOF put the entire town of Tortel, which is next to the Baker River delta, at risk. These glacial hazards are consequently topics of concern not just for scientists, but also for public policy planners, government agencies, park services, and NGOs, among others.

The September symposium in Chile will bring the world’s experts on GLOFs and glacial hazards together to talk about global experiences with these phenomena, as well as the specific implications they have for Chile’s Patagonia. For two days, Sept. 6-7, these scientists will present their research and discuss the topic with a wide audience in Santiago. Then, they will travel to the Patagonia region of Aysén for three days of site-specific talks and field visits. Their goal will be to identify what further research needs to be done in the area to better understand and prepare for future GLOFs in the country, and around the world.

While “GLOF” may not be pretty to say, it fascinating to learn about and timely to discuss. Chilean scientists and Patagonia’s recent GLOF experiences will give the international experts a lot to of material to cover during the upcoming five-day symposium.