[Hyoungmi Kim, NRDC, and Xia Xin, NDRC, at the 6th Annual U.S.-China Energy Efficiency Forum (EEF)/Barbara Finamore]

China is exploring a number of innovative methods for reducing carbon emissions and air pollution, including managing increasing power consumption through the use of demand response. As we explained in our new report, Assessment of Demand Response Market Potential and Benefits in Shanghai:

The electricity systems in China are changing. The need for large-scale integration of intermittent renewables and penetration of electric vehicles, as implied by the low-carbon energy transition, poses challenges to system operation and network management. Moreover, the ever-increasing electricity consumption and peak demand, and the emerging policy objectives of reducing environmental impacts and improving economic efficiency, underline the urgency to change the way electricity systems are operated and planned in China. There is a growing interest, particularly from high-level policy makers, to explore the potential for demand side resources to contribute to the supply-demand balance and to meet the key objectives of carbon emission reduction, environmental protection and economic efficiency.

My colleague Hyoungmi Kim joined me in Washington DC on October 23rd to give a talk at the 6th Annual U.S.-China Energy Efficiency Forum (EEF), hosted by China's National Development and Reform Commission and the U.S. Department of Energy. Hyoungmi outlined cutting-edge research involving Demand Response (DR) in the power sector, and compared the situation in both countries. Her talk was very well-received by the audience of Chinese and U.S. policymakers and officials, and I want to share with you some of her most important points:

- By definition, DR refers to programs to reduce electricity use, especially at times of system peak, by exposing customers to pricing signals that reflect the system marginal cost of generation or giving them financial incentives in return for their commitment to reduce demand when asked to do so.

- Both the U.S. and China are experiencing similar changes in the power sector, including restructuring of the grid company structure and reforms of the business model.

- Involved stakeholders in the U.S. and China power sectors, particularly for demand response, are similar, with Chinese load aggregators developing in recent years. However, the biggest difference is market maturity - though China has been trying to establish a market-based mechanism in the power sector, it does not yet have a functional market mechanism, while the US power market is very robust.

- DR resources should have a priced market value for transactions. China still relies on government incentives to implement DR programs, but this mechanism is not sustainable in the long term. China should establish a market mechanism similar to that in the US, where DR resources can be bid into the market or procured by utilities as a resource.

- NRDC released a study with Oxford University to assess what market values DR would have in China. The analysis was conducted based on actual customer data in Shanghai last year. The purpose of the study was to address a series of questions we need to answer in order to establish a market mechanism, including how much potential exists, the costs involved to realize the market's potential, who will bear these costs, how much benefit DR will bring, and how to best disburse these benefits.

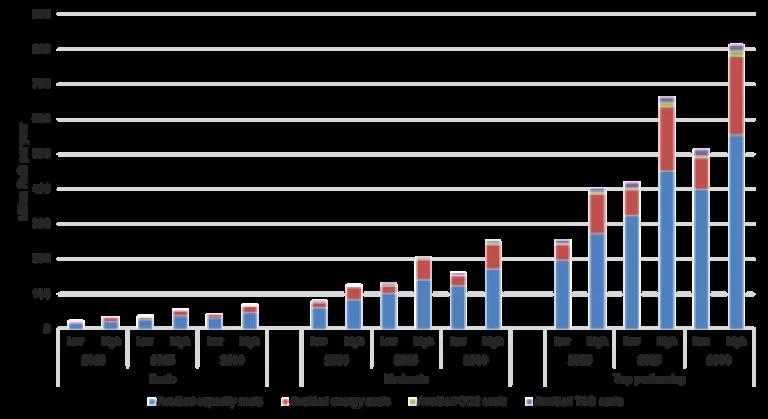

Our study demonstrates that by 2030, the avoided costs of DR in Shanghai would be worth up to 800 million RMB:

The total avoided costs of DR in Shanghai include both the avoided generation capacity costs associated with a hypothetical gas-fired plant, and the other avoided costs (including avoided energy costs, avoided CO2 emission costs, and avoided transmission and distribution costs) associated with a reference plant. This study assumes that the estimated DR market potential is achieved by load shedding only, and not by load shifting or on-site generation.

The chart shows the estimated annual total avoided costs between 2020 and 2030. It shows that total avoided costs could reach 811.2 million RMB in 2030, when future cash flows are discounted at 7%. Avoided generation capacity costs contribute most to the total avoided costs (their share ranges between 68.3% and 79.7%), and are followed by avoided energy costs (between 17.8% and 28.1%). Avoided T&D costs and avoided CO2 costs together account for between 2.5 % and 3.8% of the total avoided costs.

We look forward to working with Shanghai and other jurisdictions in China to help achieve these enormous cost savings while reducing the CO2 emissions and air pollution associated with coal-fired power plants.

This post was coauthored with my colleagues Hyoungmi Kim and Winslow Robertson.