Photo: Alvin Lin/NRDC

I don’t think I’ve ever seen such a gathering in China before. Nearly one hundred people - including city, provincial and central government officials, business leaders and NGO representatives - met in Beijing yesterday to discuss their efforts to promote environmental transparency and public disclosure of pollution data. Given the intense level of interest in this issue throughout China, the excitement in the room was palpable.

The meeting was organized by Mr. Ma Jun, China’s leading environmental activist and a recipient of last year’s prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize, known as the “Nobel Prize” for grassroots environmentalists. NRDC has been working with Ma Jun and his team for four years to rank the performance of 113 major Chinese cities in complying with environmental disclosure requirements.

Our latest report, the Fourth Annual Pollution Information Transparency Index (PITI), showed an improvement last year in the average performance of these cities, especially the top ten cities. Yet the level of improvement has slowed down: some cities still provided almost no environmental information, and others actually took big steps backwards. Most cities were still dragging their feet in three critical areas: disclosing environmental impact assessment (EIA) information, providing records of environmental violations, and releasing emissions data. We held a lively discussion to figure out why progress has stalled and how to overcome persistent challenges.

But the report was based on 2012 data, and the situation in China has changed dramatically in the last several months. Following the “Airpocalypse” that plagued much of China earlier this year, people are clamoring for more information about the deadly pollution befouling their air, water and land. As many officials struggle to respond, others are taking a proactive stance. Ma Jun and his team actually found several of these officials on Weibo, China’s largest microblogging site, where they each have an enormous following, and invited them to attend yesterday’s gathering.

One official from Jiangsu Province, whose comprehensive environmental information program has been cited as a national model, spoke passionately about the ways in which open information acts like “sunlight” to disinfect pollution. Another official from the Hunan Province People’s Congress has begun to “name and shame” flagrant polluters on his Weibo account, prompting one of the named companies to immediately invest thousands of RMB in cleanup technology. A third official from the city of Ningbo in Zhejiang Province, which has led our PITI environmental transparency rankings for all four years, described how the city has begun to require companies to disclose their own pollution data - a first in China.

Open information and broad stakeholder engagement is widely considered to be the “third wave” of environmental management that is starting to emerge around the world, an essential complement to “command and control” regulation and market-based tools. Our PITI 2012 report proposes that China establish a “Gold Standard” comprehensive disclosure system including the following elements:

- Public disclosure of online monitoring data from key polluters,

- Systematic and comprehensive public disclosure of government supervisory and enforcement information, and

- Periodic publication of emissions data covering, at a minimum, the pollutants identified in a project’s environmental information assessment (EIA) report.

In light of recent developments in Chinese law, policy statements from China’s new leaders calling for environmental transparency, the rapid expansion of internet coverage, and the best practices already underway in various Chinese cities, we believe such a Gold Standard information disclosure system is realistic and achievable. Such a system would help China overcome barriers like local protectionism, weak enforcement and low penalties for violations. It would also provide a strong push for China’s pollution reduction and energy conservation efforts (èè½åæ).

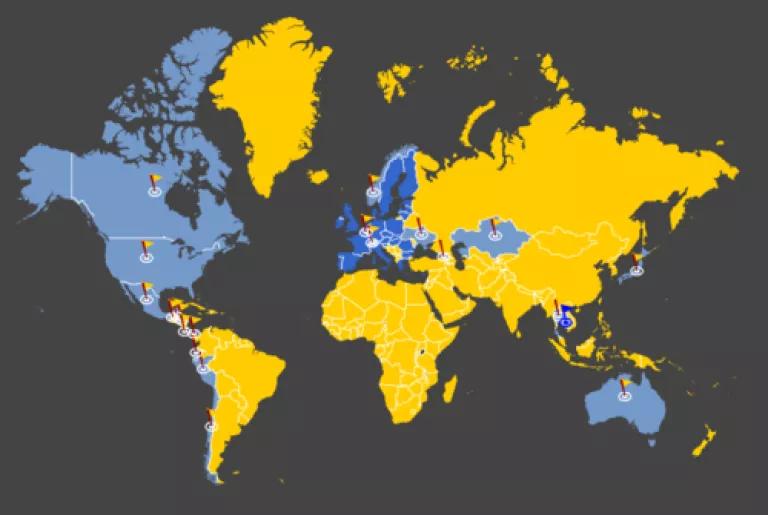

Such a system could be based on the Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (PRTR) systems that began to emerge internationally in the mid 1980’s following the worst toxic substance leak in history that killed over 3,700 people and sickened over 500,000 more in Bhopal, India. PRTRs are now in place in over 50 countries and regions around the world. A PRTR is a publicly accessible national or regional database with the following core elements:

- A listing of chemicals and/or other pollutants that are released or transferred off-site;

- Integrated multi-media reporting of releases to air, water and land;

- Self-reporting by covered industry or business categories;

- Periodic reporting (preferably annually); and

- Data available to the public.

Countries and regions with PRTRs are shaded in blue (Source: EPA)

PRTRs can provide communities with information on toxic chemical releases and waste management activities in a way that requires minimal government resources. The model also encourages broader stakeholder engagement and supports informed decision-making at all levels by industry, government, NGOs, and the public. Failure to report chemicals listed under the PRTR database results in penalties varying from country to country. In a country like China, where the cost of environmental damage reached about US$230 billion (1.54 trillion RMB) in 2010, or 3.5 percent of GDP, a PRTR could save millions in waste treatment, disposal and cleanup.

A PRTR for China may sound like a farfetched idea, but I don’t think so. An official from the city of Tianjin told us that her city is already planning to develop the first Chinese-style PRTR database in the country. And at the end of our meeting, a number of key business leaders from around the country stood up and pledged to begin voluntary reporting of their own pollution discharges. Why? Because they are also tired of keeping their children inside and wearing masks to go to work. And they also believe that everyone has a right to know the quality of the air they’re breathing, the water they’re drinking, and the food they’re eating.

Co-authored with my colleagues Wang Yan, Wu Qi and Christine Xu.

Click here for Chinese version.