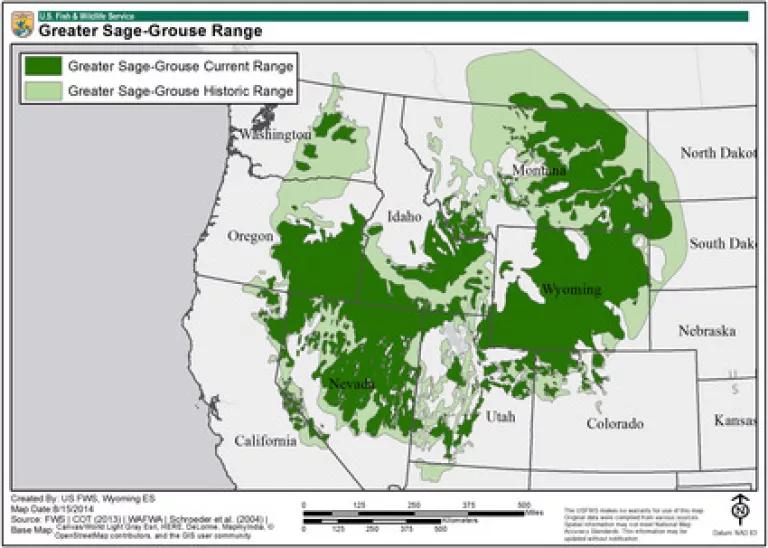

Western landscapes have much to offer with their natural splendor and vast spaces, but one other defining characteristic of the natural West is the teeming and charismatic wildlife to be found. One of these charismatic species, the Greater Sage Grouse is unfortunately in serious trouble. This magnificent bird’s historical range, which reached as far north as Alberta and as far south as Arizona, has been substantially reduced by millions of acres. In the last few decades habitat fragmentation has severely restricted the extent of the species, concentrating populations to a few core regions, jeopardizing the viability of the species.

The precipitous decline of the Greater Sage Grouse is not something that has happened over night. A century of poorly managed livestock grazing, population growth in the West, energy development, and a host of other vectors have had a major impact on the ecological health of the rangelands that the bird depends upon. But recovering the species to a point where further active intervention will not be ultimately necessary is a profound challenge. While a great deal of scientific study has been dedicated to understanding Greater Sage Grouse behavior, additional scientific insight on how to recover the species is still needed. To complicate matters, a one size fits all approach is simply not going to address the multitude of challenges that are associated with a dynamic range that still stretches for thousands of miles. Recovery measures that might be effective for Montana populations, might not be as effective for birds found in more arid climes such as northern Nevada.

Because of the negative population trend, combined with the challenges associated with conserving distinct regional populations of the bird, a range of stakeholders have been immersed in a process to develop programmatic measures to safeguard the Greater Sage Grouse. These regional initiatives have focused on tapping the expertise from a myriad of stakeholders including, but not limited to oil and gas interests, sportsmen, environmental organizations, scientists, along with state and federal agencies. With an emphasis on promulgating state specific recovery plans, the overarching goal is to deploy a range of mitigation and habitat conservation measures that will stabilize and boost Greater Sage Grouse populations. And one aspect of such a multi-stakeholder collaborative strategy is also to proactively implement recovery measures in order to avoid a federal listing under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Above: Historical range versus current distribution

The aspect of collaboration is crucial in addressing the range of unique problems that Greater Sage Grouse face. Regrettably, despite the significant investment of industry stakeholders in participating in the development of regional recovery plans, an oil and gas trade group, the Western Energy Alliance (WEA) recently launched a public advertisement campaign opposing a potential listing process for the Greater Sage Grouse under the ESA. WEA also claimed that ‘environmental lawyers’ were behind a plan to undermine the economy of the West by seeking a listing of the bird under the ESA. It is understandable why some stakeholders are acutely concerned about a potential listing, but to attack the ESA at this juncture, before we have given the collaborative stakeholder process a chance to address the critical issues facing recovery of the Greater Sage Grouse is fundamentally premature. In fact WEA’s campaign appears to be an overtly political move that seems removed from the considerable investments that have been made by industry and environmentalists alike to recover the species. That is why NRDC and its many environmental and conservation partners sent a letter to WEA stressing the importance of giving the collaborative stakeholder process a fair chance, and to work constructively toward solving how best to recover the Greater Sage Grouse.

While the collaborative process is far from perfect, the investments that have been made over the last few years should continue given they represent the best opportunity to address the myriad of complex issues that threaten the bird’s survival. In particular, the regional recovery plans need the space and opportunity to invest in additional scientific processes that could shed additional light on how best to recover the species. Getting along with those who do not see eye to eye on how critical wildlife species are managed is of course a challenge, but putting aside differences and working collaboratively is what is going to produce the best results for this most important of species.

Photo credit: Bureau of Land Management / Oregon State Office

Map credit: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service