A Year in Review: The Nuclear Fuel Cycle

Part of NRDC's Year-End Series Reviewing 2019 Climate & Clean Energy Developments

A surprising number of nuclear-related anniversaries happened this year. And yet these events are either so forgotten or have become so normalized, that they don’t seem to make much impact on the decisions we’re making today on the nuclear fuel cycle. Decades have passed since the worst nuclear accidents in the United States, and we’re no closer to cleaning up their legacy. The enduring risks and radiation contamination that persists from these disasters should remind us all why we need strong safety and environmental protection standards for the nuclear industry.

The 40th Anniversary of the Three Mile Island Meltdown

Probably the most famous commercial nuclear event in the United States is the Three Mile Island accident. On March 28, 1979, a nuclear reactor at the Three Mile Island plant in Pennsylvania partially melted down due to a combination of technical malfunction and human error.

The accident led to increased regulation of nuclear power plants. But that heightened care when it comes to commercial nuclear reactors has eroded over the years. This year, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) granted the first subsequent license extension, which will allow the Turkey Point reactors to stay open an additional 20 years for an unprecedented total of 80 years.

If there is one plant that is likely to have some challenges functioning until the 2050’s, it’s this one. The Turkey Point plant sits on the coast south of Miami, an area scientist know is experiencing sea level rise faster than expected. Yet in granting the license, the NRC failed to consider realistically how climate impacts like sea-level rise and temperature will affect the plant’s future safety and environmental impacts.

Adding insult to injury, the NRC granted the license even though the review process is far from over. NRDC has been working with Friends of the Earth and Miami Waterkeeper to challenge the environmental impact statement required as part of the license renewal process. While the Atomic Safety and Licensing Board rejected all of our claims, we are in the process of appealing the decision to the full Nuclear Regulatory Commission. If we lose there, a court fight could follow. So while the NRC staff wants to pretend it can’t lose, we still have a lot of fight left.

The 40th Anniversary of the Church Rock Uranium Mill Spill

The largest radioactive accident in the United States had nothing to do with a nuclear reactor or bomb. Rather, it was caused by the first step in the nuclear fuel cycle, uranium mining. On July 16, 1979, a dam holding back a pond filled with uranium mining waste broke. It released 94 million gallons of acidic, radioactive liquid and approximately 1,000 tons of solid radioactive and heavy metal waste into a local river, which then took the acid, heavy metals, and radiation downstream through a wide swath of the Navajo Nation. Tribal members were not warned about the toxicity in their primary water source until days later and then were given the most minimal assistance.

The Church Rock uranium mill spill was a terrible, singular, and instantaneous disaster. But it’s not the only legacy of uranium mining. The pond that spilled at Church Rock was one of many similar unlined, dirt ponds storing radioactive and toxic waste. Over the lifecycle of these ponds, millions of gallons of toxic material leaked into the groundwater, polluting a precious resource in the desert West.

But that was then—right? Wrong.

Domestically, uranium now is largely produced through a process called in situ leach mining. Rather than dig uranium straight out of the earth, in situ leaching sends liquid underground to dissolve uranium directly off the underground ore. The liquid is then pumped back to the surface, carrying with it the dissolved uranium. The problem is, the law hasn’t kept up with the new technology. There are no specific rules to protect groundwater from this type of mining, so instead the NRC has cobbled together a mess of complicated and ineffective standards for protection of public health and the environment. These haphazard regulations theoretically require groundwater be cleaned up after the uranium mining is done, but effective cleanup and restoration to pre-mining water quality has never happened, not once.

The Environmental Protection Agency had prepared the first strong, protective standards for uranium mining, but the Trump administration withdrew them. Instead, in early 2019, the NRC said it will move to codify its existing inadequate rules. NRDC has interceded to halt NRC from moving forward, and we await NRC’s responses to our comments. Essentially, it is EPA’s duty to first update its regulations so that the NRC has rational standards to work from. Should the NRC proceed with this ill-advised rulemaking, it’s very likely to get even more contentious.

The 60th Anniversary of the Nuclear Reactor Meltdown at Santa Susana Field Laboratory

Twenty years before the Three Mile Island disaster, a test reactor at the Santa Susana Field Laboratory in Simi Valley, California had a partial meltdown. And this wasn’t the only accident at the site.

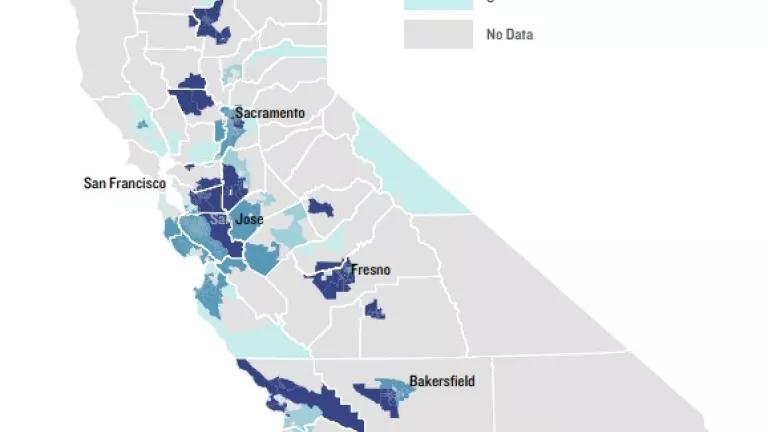

Today, Santa Susana remains one of the most contaminated site in California, even though Boeing, NASA, and the Department of Energy signed legally binding agreements with California to have cleanup finished by 2017. And this year NASA and the Energy Department are considering cleanup alternatives that would abandon the majority of the waste in place. NRDC is working closely with local organizations, community members, and the state of California to ensure that NASA and the Department of Energy don’t renege on their cleanup promises.

The 75th Anniversary of the Nuclear Industry

It’s been three quarters of a century since the world’s first full scale nuclear reactor (rather than test reactor) came online. Named the B-Reactor, this production-scale plutonium nuclear reactor was a main part of the Hanford site in Washington, one of the major Manhattan Project facilities used during World War 2 to develop and create nuclear weapons.

While many continue to perpetuate the myths about its promise, the vexing problems the nuclear fuel cycle poses are on vivid display at Hanford and the other the major Manhattan Project sites, including the Savannah River Site and the Idaho National Lab: millions of gallons of waste sit in leaky tanks with little to no progress on cleanup.

So far, Congress has been unable to come up with a durable plan to permanently dispose of nuclear waste, whether the weapons waste that sits at Hanford, the Savannah River Site, and Idaho National Lab or the commercial waste that sits primarily at commercial nuclear reactors. NRDC was busy this year testifying before Congress about a progressive way we can end the stalemate regarding what to do to finally address this problem. Senior Attorney Geoffrey Fettus suggested removing the exemptions from protective environmental laws that nuclear waste currently enjoys and instead treating nuclear waste like any other toxic substance. Placing nuclear waste under environmental laws wouldn’t make it less radioactive or toxic, but it would finally provide the impetus for more protective standards and a better chance for actual disposal deals.

In the meantime, it’s the Department of Energy’s responsibility to deal with safely storing and managing the weapons waste. Yet rather than conduct a full cleanup of the radioactive and toxic legacy of the nuclear weapons complex, the Energy Department continues to try to abandon it in place. The Energy Department is ending 2019 by proposing to reinterpret the term “high-level waste,” thus giving itself the authority to wave a magic wand over 10,000 gallons of high level waste at the Savannah River Site so that it can be disposed of in a cheaper, less secure manner. NRDC has teamed up with states, tribes, and community organizations across the country to ensure that the Energy Department follows the law as Congress intended until Congress can work out a better solution.

Looking back, we can see how nuclear energy and nuclear weapons pose unimaginable risks to our citizens, our water, and our landscape. Moving forward, we will keep fighting to ensure those risks are managed to the highest degree possible.