I grew up next to San Francisco Bay and these days I commute to my NRDC office by boat, riding the ferry past the Golden Gate Bridge and Alcatraz Island.

Most people know the Bay as the iconic backdrop for the city that shares its name. Some people are familiar with the Bay’s importance as habitat for many fish and wildlife species, including salmon and Dungeness crab. But fewer people recognize the Bay as an estuary—the largest on the west coast of the Americas—or understand that the key feature that makes it such an amazing ecosystem is out of sight, below the surface where fresh waters from California’s largest rivers meet and mix with saltwater from the Pacific Ocean. Freshwater inflow to an estuary is like fresh water is to us – without it we wither and die.

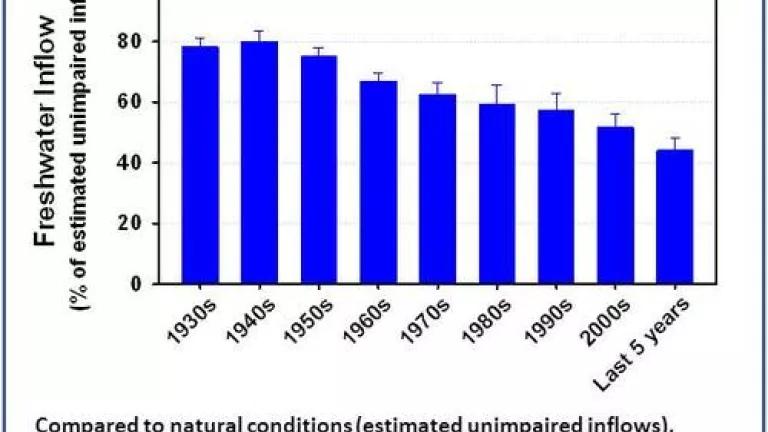

Last year, as part of a team of scientists tasked by the San Francisco Estuary Partnership to evaluate the “State of the Bay,” I took a look at the state of freshwater flows into the estuary. I compared actual inflows, the amount of fresh water that actually reached the Bay, to the inflows that would have occurred if there were no dams and water diversions on the Bay’s rivers, referred to as estimated unimpaired inflows.[1] What I found was disturbing evidence that our human impact on the estuary’s life blood is enormous and, despite efforts during the past couple of decades to protect this vital ecosystem and its valuable fisheries, increasing.

For the first 20 years after the state and federal water projects that divert water from the Bay’s tributary rivers and its Delta became fully operational (1970-1989), freshwater inflows to the estuary were reduced by an average of 39%. By the 2000s (2000-2009), inflows were reduced by 48%, on average, and, for the most recent five-year period (2007-2011), the average reduction was a whopping 56%.

Under natural conditions, the amount of fresh water that flows into the Bay varies substantially from year to year, reflecting California’s unpredictable cycle of floods and droughts. Today, because of escalating water diversions from the Bay’s rivers and the Delta, the estuary experiences drought-like inflow conditions much more frequently. Since 1970, the frequency of years with inflows less than 15 million acre feet – the upper bound of the amount of water that nature (as estimated by unimpaired inflow) typically provided in “very dry” years[2] – has doubled, from 26% to 50%. In nearly a third of these years (13 of 42 years), actual inflows were less than seven million acre feet, an extreme low inflow condition that the Bay would have experienced only once during this period under natural conditions.[3] During the last decade (2002-2011), the estuary experienced seven years with “very dry” inflow conditions, despite the fact that only two of those years were actually “very dry” based on watershed runoff and estimated unimpaired conditions. With this 350% increase in the frequency of “very dry” years, San Francisco Bay is now in a persistent, man-made drought.

Can the Bay’s ecosystem—its salmon, Dungeness crab and host of other fish and wildlife species—go on like this? Probably not. Decades of monitoring and scientific research have shown that reduced freshwater inflows are a major cause of habitat degradation and declining fish populations in the estuary: since the 1970s, populations of many of the most common species have plunged by 66-98% (see here and here for recent research syntheses, as well as my earlier post).[4]

Water diverted from the Bay’s watershed supplies farms and cities throughout the central and southern regions of the state. But, as the Association of Bay Area Governments stated in their recent resolution, it is not sustainable to manage California’s water resources to support distant needs at the expense of the estuary that is so vital to their economy and identity. Nor is it compatible with the state’s mandated co-equal goals for managing the Bay’s watershed to support a healthy estuarine ecosystem and provide reliable water supplies, or the State Water Resources Control Board’s responsibility to protect the Bay’s public trust resources.

But there is another, larger story here. Although some parties engaged in California’s ongoing Bay-Delta planning efforts argue that inflow-related environmental conditions in the estuary are controlled by the unpredictable amounts of rain, snow and runoff from the mountains, these results show that that’s not true anymore. For the nourishing freshwater flows into the west coast’s largest estuary, Mother Nature is not really in control anymore – we are.

As a scientist, I find this an intriguing result. But as a citizen who cares about the Bay, my fellow Californians and our future, I think this is a reminder of our responsibility to find a better balance in our management of natural resources and natural treasures.

[1] Data for freshwater inflows to the estuary (also referred to as Delta outflow) are from the California Department of Water Resources Dayflow datset (actual inflows) and California Central Valley Unimpaired Flow Data (estimated unimpaired inflows). Estimated unimpaired inflows are the best available proxy for “natural” inflows.

[2] “Very dry” is defined as the driest 20% of years in the last 80 years.

[3] In the two driest years on record, 1931 and 1977, estimated unimpaired inflows to the estuary were 7.5 and 5.6 million acre feet, respectively. In all other years of the driest 20% of the record, the estimated unimpaired inflows were greater than 10 million acre feet.

[4] Percent declines calculated from California Department of Fish and Game Fall Midwater Trawl survey data for 1970-1979 and 2007-2011.