With CFC-11 Success Comes a Time to Reflect (Pt.II)

This is part II of a 2-part blog series.

In part I of this blog series, I describe the story of an unexpected spike in emissions of CFC-11, a banned ozone-destroying chemical, in what appears to have been a major violation of the Montreal Protocol’s worldwide phaseout of the dangerous gas. Emissions are now back on the decline, according to new research published today in the journal Nature, marking the beginning of the end of this troubling incident.

With success afoot, now’s the time to look at what the CFC-11 story has taught us about the Montreal Protocol, and study in brief its strengths and vulnerabilities. If today’s success holds, the treaty’s response will have been a major success, brought on by collaboration among nations, the scientific community, non-governmental organizations, and more. But how did it come to this? And how can we avoid similar problems cropping up in the coming decade, as the Montreal Protocol’s workload continues to grow?

An International Response

According to the new studies, CFC-11 emissions began declining shortly after the international community learned of the problem and turned its attention to solving it. It seems, then, that the international community’s response, plus the domestic actions of the implicated country, were key drivers to bringing illegal emitters into line.

Atmospheric scientists from NOAA and their international colleagues were first to see and report on the problematic CFC-11 emissions trend. Upon hearing the news, the parties to the Montreal Protocol promptly convened a team of international experts, myself included, to investigate the cause. The Montreal Protocol maintains environmental, technical, and scientific advisory panels and convenes expert task forces when urgent issues emerge, a capability that proved essential in solving the problem this time.

We investigated potential sources and scenarios that could explain the observed uptick in CFC-11 in the atmosphere. Our research concluded that the most likely source of emissions was unreported production of CFC-11 used to manufacture insulation foams. This conclusion was consistent with previous investigations by the Environmental Investigation Agency and the New York Times that detected the chemical in foams sold in China, as well as a later investigation by the Chinese government.

CFC-11 Incident Exposes Gaps

Without scientists continually monitoring the planet’s atmosphere, we would probably never have caught onto this problem. Global atmospheric monitoring is the main backstop—the strongest line of defense—that the Montreal Protocol has to ensure that the treaty’s goals are attained.

Every year countries submit data on their domestic production of regulated substances. Data reporting is critically important, but it’s not perfect. Collection methods, for example, vary from country to country, and national governments do not always have clear visibility into what happens within their borders. Without atmospheric monitoring, the Montreal Protocol community would be left without a way to check the veracity of this national self-reporting program.

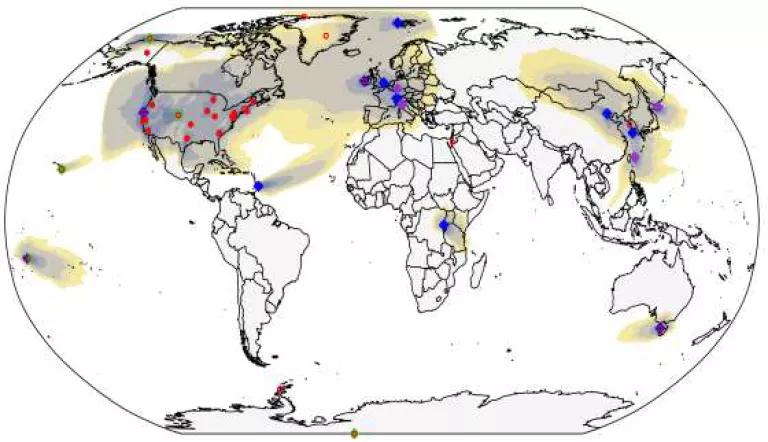

The monitoring network is thus vital to the enforcement of the Montreal Protocol and needs to be expanded. Our current monitoring capabilities only cover North America, Western Europe and East Asia; the rest of the world is not regularly monitored. For example, an important blind spot is India, which is expected to account for about 10% of global refrigerant use and emissions by midcentury. These types of gaps made it impossible for atmospheric scientists to precisely pinpoint and break down all the geographic contributions to this problem. As a result, we’ll never get a perfect picture of what happened in this story or any other like it.

The current observational networks emerged through successful international collaborations among national and international scientific entities. Additional expansions, however, have been largely ad hoc. The credible and reliable expansion of monitoring capabilities will require us going back to the successful model of old, with cooperative and transparent contributions from all. Old and new networks alike should share data publicly, including the network currently being developed in China. Operators should be transparent about their methods and assumptions, including each system’s calibration standards and the modeling approach used to trace the source of emissions.

We must also work together to tackle potential illegal trade of CFC-containing foams. Most small and medium sized foam producers use pre-blended polyols, a mixture of raw materials and blowing agent like CFC-11, that are often imported. All parties must remain vigilant and ramp up inspections of imports and testing of domestically produced foam products to ensure that they do not contain CFC-11 or other controlled substances.

To achieve all that, the parties should prioritize capacity-building activities in developing countries. Additional scientific capacity and robust measurement capability is key to each country’s participation in our shared role of protecting the ozone layer. Even the Scientific Assessment Panel’s members are volunteers; the parties should make sure they are providing enough financial support to these communities, where applicable, to keep them fully engaged.

This time around the Montreal Protocol’s institutions, with their reputation for transparency and spirit of cooperation, proved able to respond rapidly to new scientific data by applying diplomatic, multilateral pressure to those responsible. But gaps in the treaty’s reporting and enforcement mechanisms were exposed and must be repaired to secure the immense benefits of the Montreal Protocol.

Even still, the CFC-11 story is proof that, despite their glitches and complexities, international environmental treaties work.

This good news renews our confidence in international cooperation. But it also lays out our work to ensure that the Montreal Protocol is equipped with the right tools to protect the stratosphere and fulfill its newest role in phasing down hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), the third generation of climate-warming refrigerant chemicals that no longer have a place in our skies.