A new report released today by NRDC brings together recent information about a widespread pollution problem in the Mississippi River Basin and Gulf of Mexico and calls attention to a legal controversy that has made it more difficult to protect resources in the basin that help reduce this pollution. The report also provides a roadmap for safeguarding these resources under the law.

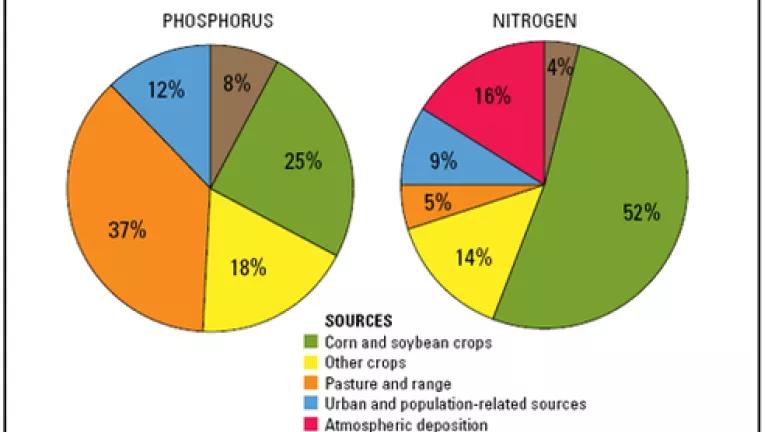

Each year, enormous quantities of nitrogen and phosphorus compounds from a variety of sources (but largely due to agricultural sources) flow down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico.

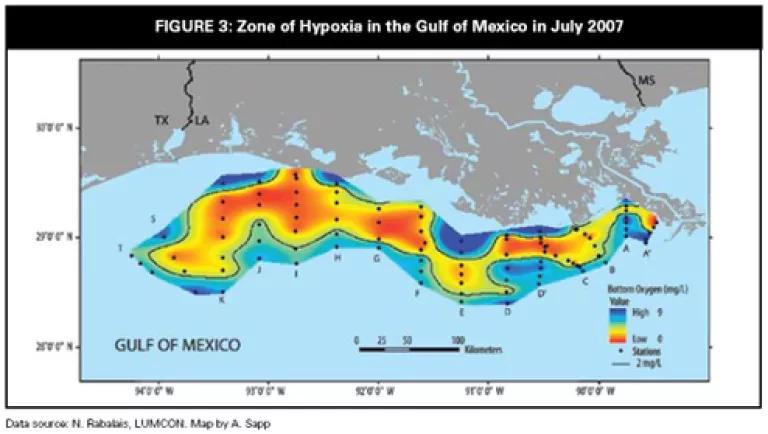

In the summer, this nutrient pollution fuels the growth of algae blooms in the Gulf. When the algae die and decompose, an area of the Gulf's bottom layer of water becomes so oxygen-deprived (or "hypoxic") that fish and many other aquatic organisms either flee or die. In recent decades, the average size of the "Dead Zone" has reached state-sized proportions. For instance, in 2007, the "Dead Zone" was approximately the size of New Jersey.

Scientists have found that wetlands and small streams are capable of removing nutrient pollution before it pollutes major waterways. As the Bush White House - which could hardly be described as an environmental zealot -- recently explained, wetlands in the Mississippi River Basin "retain nitrates and phosphates that would otherwise drain from adjacent farmlands." The administration also noted that ensuring that nutrients pass through such features "will help reduce the size of the hypoxic zone in the Gulf of Mexico and provide habitat, flood protection, and clean drinking water." The obvious upshot of that conclusion is that these resources ought to be protected from harm as much as possible.

For many years, the federal Clean Water Act had protected small streams and wetlands from unregulated pollution or destruction. However, since the Supreme Court handed down a pair of messy decisions in 2001 and 2006, the federal agencies charged with implementing the Act have given unclear guidance about what kinds of water bodies remain protected, and have effectively written off roughly 20 percent of the wetlands in the continental U.S. Courts also have struggled to figure out what kinds of resources are still covered.

As a result, many of our country's smaller streams and wetlands are at risk of being polluted or even buried by mining companies, developers, industrial wastewater sources and others without so much as a Clean Water Act permit to limit the effect that the activity will have on aquatic resources. And some of that pollution could contribute to the Dead Zone.

In light of these facts, NRDC's report proposes a simple solution - restoring the Clean Water Act's protections to as many of those water bodies that it covered before the Supreme Court's interventions, as fast as possible. It shows (I've got to use my darn law degree once in a while) how the existing Act and agency rules can be interpreted today to protect a great deal of the nation's remaining small wetlands and streams, even considering the Supreme Court decisions, but it also highlights the need to bring a permanent solution to the problem the Court created. Only Congress can fully and certainly restore the law's safeguards to our water bodies; fortunately, leaders in both houses of Congress have been fighting for a bill that will do that - the Clean Water Restoration Act.

Will this action alone eliminate the Dead Zone? No. It was here before the Supreme Court screwed up the law, and fixing the law will not bring back lost pollution sinks or make direct cuts in the amount of pollution occurring in the Mississippi River basin. It is, however, critical that we stop the bleeding, not dig ourselves deeper into a hole....use whatever metaphor you like. Much more needs to be done, as I discussed in a previous post, but starting with the obvious solution of reinvigorating the Clean Water Act is seriously overdue.