Fifty Years After 1969: How Far Have We Come?

Nineteen sixty-nine was a pretty big year. This week in 1969, Apollo 11 astronauts traveled to and walked on the moon. That same year, the Stonewall Uprising galvanized a civil rights movement that continues today. President Nixon was inaugurated. The first episode of “Sesame Street” aired. It was such a momentous year that me being born in a Battle Creek, Michigan, hospital (Mom says she could smell the Froot Loops from the delivery room!) surprisingly doesn’t make the year’s Wikipedia page.

I’m not going to talk about those things or even the last public performance by the Beatles. Instead, this post focuses on the legacy of a 1969 event that had occurred a number of times before—the Cuyahoga River in Ohio caught fire. As it had roughly a dozen times, oil and debris floating on the river’s surface ignited when a stray spark fell in the river.

The June 22, 1969, fire was not very remarkable—except inasmuch as any water body on fire is really darn weird—and did not receive great attention at the time. In fact, it wasn’t photographed before being extinguished relatively quickly, such that a famous Time magazine story about the fire used a photo from 1952. What makes the 1969 fire noteworthy is that it was the last Cuyahoga River fire.

Just a few years after 1969, in response to numerous disturbing pollution events like the Cuyahoga River fires, Congress passed the law now known simply as the Clean Water Act. That law declared an ambitious objective: “to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters,” and its goals of making waters fishable and swimmable by 1983 and eliminating all pollutant discharges by 1985 reflected Congress’ urgency about making progress. To get there, the Clean Water Act has a suite of programs that require pollution sources to limit their impact on waterways and that demand cleanup of water bodies that aren’t clean enough for their intended uses.

This post checks in on the Clean Water Act 50 years after the last Cuyahoga River fire.

The Good News: The Clean Water Act Works

Water pollution levels have generally improved compared to 50 years ago. Some trends are depicted in the images below, from a recent academic analysis.

The Clean Water Act has driven pollution controls since 1972. Because of the law, sewage from our homes and businesses ordinarily receives treatment before it’s discharged. Industry-specific discharge standards now prevent more than 700 billion pounds of toxic pollutants every year from being dumped into the nation’s waters. And the rate of wetlands loss decreased substantially compared to the pre-Clean Water Act era.

And we all probably know waterways that are much better today because of the law. The Charles River in Boston, the Potomac in D.C., and Lake Erie are all hugely improved since 1969. And what about the poster child for polluted U.S. waterways, the Cuyahoga? Earlier this year, Ohio declared that eating fish caught in from the river and its watershed is safe.

The Bad News: The Clean Water Act Hasn’t Achieved its Goals

As successful as the law has been, the country still has a long way to go if we are going to achieve the Act’s goals of ensuring fishable and swimmable waters and eliminating pollutant discharges (both of which were supposed to be accomplished by the mid-1980s).

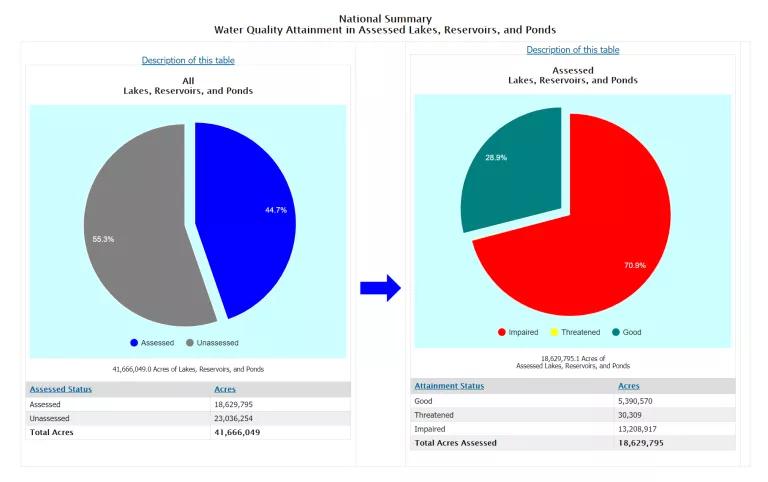

Look at the state of water bodies today: 53 percent of assessed rivers and streams; 71 percent of assessed lakes, reservoirs and ponds; and 80 percent of assessed bays and estuaries don’t meet one or more state standards meant to ensure that waterways are safe for things like fishing and swimming.

In addition, a massive toxic algae outbreak has closed all of Mississippi’s Gulf Coast beaches, with the state warning that people are at risk of “rashes, stomach cramps, nausea, diarrhea and vomiting.” These outbreaks are fueled by water pollution and are popping up all around the country, with scary reports coming in from New Jersey to the New York Finger Lakes to California. And the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recently warned that the Gulf of Mexico “dead zone,” an area where algae decomposition sucks oxygen from the water and can kill aquatic life, will be very large this summer, due to major rainstorms washing pollution down the Mississippi River.

The Ugly News: EPA’s Assault on the Clean Water Act

Against this backdrop of significant, but also significantly incomplete, progress, the federal agency responsible for implementing and enforcing the Clean Water Act—the Environmental Protection Agency—has launched a broad and relentless attack on numerous protections in the law. If EPA succeeds in making these radical changes, the agency will make water pollution substantially worse.

First, EPA proposed to repeal the 2015 Clean Water Rule, which clarified what water bodies EPA would protect from harm and which was based on a robust scientific record. In its place EPA proposed the Dirty Water Rule, which would exclude at least 18 percent of streams (the actual figure is likely much higher) and more than half of wetlands from protection. Remarkably, however, EPA utterly failed to assess what its Dirty Water Rule will mean for drinking water safety, its potential to render waterways too polluted for fishing or swimming, the likely increases in flooding-related damages to property when protective wetlands are destroyed, or the viability of water-reliant businesses. The Dirty Water Rule is so poorly conceived and reckless that states, tribal nations, fishermen, landscape architects, river guides, brewers, and lots of scientists (to name a few) told EPA to drop it.

Second, EPA also plans to make it easier for wastewater plants to release partially-treated sewage during rainstorms. As 69 conservation groups told EPA, pursuing this rollback makes no sense given how little evidence the agency has that authorizing increased sewage blending will not cause harm:

A common theme in stakeholder discussions has been the lack of complete or even adequate data about many aspects of blending: how many facilities do it, what the consequences are to water quality and human health, what the environmental justice impacts are on communities affected by blended discharges, and what can be done to avoid blending or reduce the risks it poses, among other questions. These information gaps are important, especially given that the limited information available shows that the discharge of blended sewage contains higher levels of pathogens that are dangerous to human health.

Nevertheless, EPA is pushing forward with its plan, with a proposed rule expected in the fall.

Third, EPA has fought efforts to get long-overdue regulations aimed at avoiding and minimizing spills of hazardous substances. Despite a more than 45 year failure to issue spill-prevention rules for industrial facilities storing toxic chemicals as the law requires, EPA proposed to ignore this obligation indefinitely. In addition, EPA’s disregard for the threats from chemical spills extends to high-hazard facilities, as it missed (by more than 25 years) a deadline for rules requiring plans to prevent and respond to worst-case scenario spills of hazardous substances.

Fourth, EPA already weakened, and plans to weaken further, rules about siting, operating, monitoring, and closing leaky, dangerous coal ash dumps. The agency is pursuing this rollback even though these facilities’ own monitoring reveals that that 91 percent of coal plants have unsafe levels of one or more coal ash constituents in their groundwater, even accounting for contamination that may be naturally occurring or coming from other sources.

Fifth, EPA announced it would treat polluters who harm waterways if their discharge first travels through groundwater as exempt from the Clean Water Act’s discharge permitting program. This newly-announced loophole could tear the heart out of the Act, by allowing polluters to re-route their waste to groundwater and avoid the pollution controls that come when dischargers get permitted.

Sixth, EPA plans to hamstring its experts’ ability to stop the dumping projects that cause unacceptable harms to water bodies. This authority provides a critical check on the worst projects, such as the Pebble Mine proposed for the Bristol Bay watershed in Alaska.

Seventh, EPA delayed and is planning to weaken toxic pollution discharge standards for power plants. These facilities represent the country’s largest single source of toxic water pollutants that hurt people and wildlife. As EPA itself described:

The pollutants in steam electric power plant wastewater discharges present a serious public health concern and cause severe ecological damage, as demonstrated by numerous documented impacts, scientific modeling, and other studies. When toxic metals such as mercury, arsenic, lead, and selenium accumulate in fish or contaminate drinking water, they can cause adverse effects in people who consume the fish or water. These effects can include cancer, cardiovascular disease, neurological disorders, kidney and liver damage, and lowered IQs in children.

But does this bother the current leadership of EPA? Apparently not, as it plans to propose its rollbacks in the coming months.

Finally, the administration plans to short-change states’ and tribal nations’ rights under the Clean Water Act to review federally-permitted projects like pipelines and dams and impose conditions (or block the project, if necessary) in order to prevent harm to their waterways. EPA recently issued new policy guidance undercutting states' and tribes’ rights and will soon propose further weakening regulations.

The Hopeful News: The Clean Water Act Ain’t Dead Yet

It is sad to say, but the greatest threat to the nation’s water quality and the greatest impediment to its ability to achieve the goals of the Clean Water Act is the agency that is supposed to implement these protections.

But EPA’s attacks on the law are by no means a done deal. Many of these reckless schemes are just proposals, and the public will have the ability to weigh in on them to demand that they be abandoned. Others are being challenged in court or will be, where EPA’s refusal to consider critical facts, public input, and the language of the Clean Water Act will be major liabilities to the agency’s rollbacks.