In the dead of summer, while the country was away on vacation, the State Department announced that it had received a new cross-border oil pipeline application from none other than TransCanada, the company behind the controversial proposal for the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline. The application for the new proposed pipeline--the "Upland Pipeline"--was actually submitted in April, but it took more than three months for the public to get its first peek at the details of TransCanada's latest attempt to cross the border between the United States and Canada. TransCanada proposes to connect the Upland pipeline to another controversial pipeline project--the company's proposed Energy East tar sands pipeline. With a public comment period of only 30 days ending on August 31, NRDC, Sierra Club, and the Center for Biological Diversity have submitted comments strongly urging the State Department to delay its review of this ill-conceived project until after TransCanada provides a convincing rationale for why it should be built in the first place.

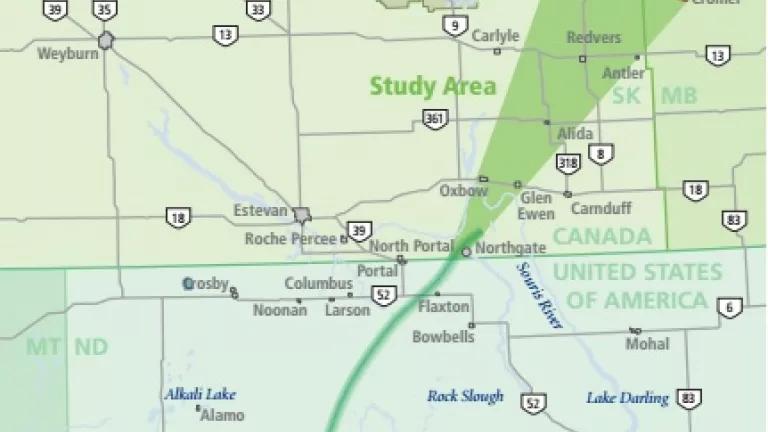

TransCanada's proposed route for the Upland Pipeline. Image courtesy for TransCanada Corp.

The proposed Upland Pipeline would be a 240-mile, 20-inch diameter oil pipeline running from Williston, North Dakota north to Moosomin, Saskatchewan or Cromer, Manitoba. At its peak operating capacity, the pipe could carry 300,000 barrels of oil per day (bpd). If those few data points don't already cause you to scratch your head, consider the following: According to TransCanada's filing with the State Department, this project is designed to serve North Dakota oil producers operating in the Bakken region by transporting their oil north to an interconnection with the unbuilt, unpermitted, Energy East tar sands pipeline. In fact, shipping contracts on Upland--totaling only 70,000 bpd, or 23% of the pipeline's capacity--are conditioned on Energy East's eventual construction. Stranger still is the fact that Energy East is so oversubscribed with tar sands that it doesn't have the available capacity to handle all the oil Upland could carry,[1] nor is there a refinery market in Saskatchewan capable of processing the excess capacity. And finally, the Upland proposal follows on the heels of three other canceled pipelines[2] that Bakken producers decided not to support.

All of this begs the question: why does TransCanada really want a pipeline this big from the Bakken region right now? There's no way to be certain--TransCanada claims that the project will meet Bakken producers' shipping demands and that Upland will help to take oil off the rails. Of course, reality on the ground has shown weak demand for new Bakken pipelines and a producer preference for using rail. Even worse, if Upland were eventually filled to capacity and Energy East were eventually built, Upland would likely just divert U.S. rail traffic to railroads crossing Canada, as Energy East's minimal excess capacity would leave Bakken oil stranded in Saskatchewan or Manitoba with no other way to move east. Economic realities also don't help to support TransCanada's stated reasons for building Upland. The U.S. Energy Information Agency predicts that Bakken oil production will peak at just about the same time that Upland would enter service in 2020 if it were approved as quickly as possible. From that point on, demand for shipping capacity will be on the decline, making the future for any new pipeline a weak and losing prospect.

Searching for a justification for the Upland pipeline seems inevitably to turn to other oil production areas, primarily Alberta's nearby tar sands. Given TransCanada's continued woes with trying to sell Canada and the U.S. on the need for new tar sands pipelines, a cross-border permit application for a new oil pipeline with few rational justifications raises the prospect that this application is all about securing the right to cross the U.S.-Canada border, and much less about moving Bakken oil north (or taking it off the rails).

Indeed, we've seen clever schemes from other pipeline companies--Enbridge in particular--to use existing cross-border permits to attempt to avoid major scrutiny of massive increases in pipeline volume or significant changes to an original project's design. Elsewhere, we've seen pipeline companies reverse crude oil pipelines so that they can begin carrying tar sands crude oil south or east. Given the fact that there are a few other pipeline proposals in the works in close proximity to the Upland proposal that could create a relatively direct route to the Gulf Coast--see the map below--a future reversal of Upland for carrying tar sands is not far-fetched and must be seriously considered by the State Department as it scrutinizes TransCanada's application.

Upland Pipeline and proposed/existing pipelines nearby. NRDC image.

Regardless of TransCanada's long-term plans for Upland, the fact is that we should not be building brand-new oil infrastructure that facilitates growth of the oil industry while simultaneously seeking to confront the threat of climate change. We have the production capacity and transport capacity necessary to meet current oil demand. From this place, our only rational path forward is to lower demand, phase out production, and transition to alternative energy sources. In other words, to avoid climate catastrophe, we cannot proceed with energy policy that looks anything like business as usual. New projects like Upland are poster children for business as usual practices--low-hanging fruit that should be easy for decision-makers to choose to point to as climate change drivers that cannot and should not move forward.

[1] Energy East has a design capacity of 1.1 million bpd, 930,000 bpd of which has been reserved for oil sourced solely from Alberta. This leaves 170,000 bpd of open capacity for shippers from elsewhere, a total far small than the 300,000 bpd potentially arriving via Upland.

[2] These include the Oneok Bakken Crude Express pipeline, the Koch Industries Dakota Express pipeline, and the Enterprise Products pipeline (total combined capacity of ~800,000 bpd).