Preparing U.S. Hospitals for COVID-19 and the Climate Crisis

Learn more about NRDC’s response to COVID-19.

The COVID-19 emergency has stretched America’s healthcare system to unthinkable limits. This summer, the cracks that have formed may lead to full-scale collapse as hospitals and other care facilities face the dual threat of the pandemic and climate-fueled weather extremes.

Surges in COVID-19 cases have forced hospitals to set up extra beds in cafeterias and conference rooms. The financial pressures of the pandemic are making it hard for rural hospitals—already in short supply in the United States—to keep their doors open. And the virus has infected thousands of healthcare workers, thanks in part to severe shortages of personal equipment.

Although some hospitals may be past the worst of the first wave of the pandemic, many states aren’t expected to see a peak in COVID-19 cases until the hurricane, heat wave, and wildfire seasons are underway.

What else could go wrong? Plenty.

Climate-fueled disasters such as hurricanes and wildfires can damage healthcare facilities and vehicles, disrupt supply chains for medical supplies and equipment, block essential transportation routes, and destroy patient records—making it harder for health professionals to get to work and for patients to get timely medical care.

Furthermore, healthcare facilities are often short-staffed during major storms, floods, or fires, and healthcare workers commonly endure long shifts, insufficient or unsafe food and water supplies, and inadequate bathroom facilities.

Evacuations are one of the most disruptive and dangerous threats to hospitals if COVID-19 and extreme weather coincide. From 2000 to 2017, U.S. hospitals reported 89 evacuations due to wildfires, hurricanes, and other storms. Evacuation threatens the health and safety of patients and staff at the best of times. During the current pandemic, moving people around flies in the face of physical distancing guidelines and could facilitate further spread of COVID-19.

Mass evacuations can also stress healthcare systems hundreds of miles away from disaster zones. In the month after Hurricane Harvey, for instance, emergency departments in at least 10 Dallas-Fort Worth hospitals experienced patient surges of 600 percent due to visits from Houston-area evacuees.

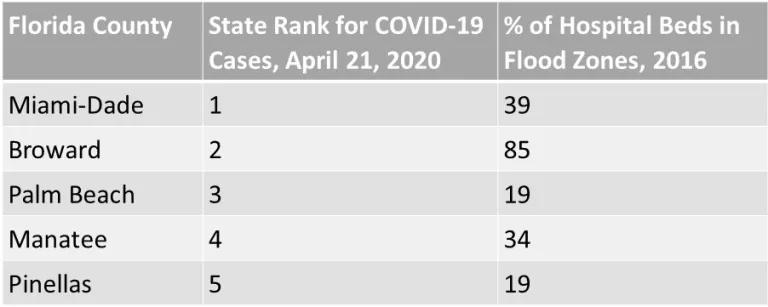

Flooding is a common reason hospitals choose, or are forced, to evacuate during hurricanes. A 2017 analysis by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found 318 hospitals and over 4,400 nursing homes in the United States within flood hazard zones. Together, the facilities included more than 52,000 hospital beds and more than 162,000 nursing home beds. These stats could spell trouble for hospitals nearing capacity limits due to COVID-19. For example, in the five Florida counties with the most COVID-19 cases to date, 19 to 85 percent of beds were in flood hazard zones in 2016.

Not prepared for the worst case

The pandemic is an important reminder that hospital leaders should consider the worst of the worst-case scenarios when developing and updating disaster plans. It’s also an important reminder that climate-related hazards must be integrated into disaster planning—not sidelined as a separate issue.

Nature will neither politely wait for our healthcare system to deal with one disaster at a time nor just offer disasters we’ve seen before. (Just think: How many times in the last six weeks have you seen the word “unprecedented” used to describe COVID-19?) That’s particularly true as the world continues to increase the odds of weather extremes by breaking records for emissions of climate-warming pollution.

Hospitals and other healthcare providers have certainly improved their preparedness for health emergencies in recent years, according to the 2019 National Health Security Index. But despite those improvements, the nation scores particularly poorly on providing high-quality patient care and protecting emergency responders and other workers in the wake of disasters.

There’s a better path

For years, NRDC has called for the federal government to help our healthcare system prepare for the unavoidable impacts of climate disruption. In February, as part of her climate and health testimony to the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis, NRDC President and CEO Gina McCarthy reiterated the need for Congress to advance climate resilience in hospitals.

But hang on, why should the government get involved in hospital preparedness? Shouldn’t that be left to the private sector? In fact, just 21 percent of the more than 6,000 hospitals in the U.S. are run as for-profit facilities. And more than 200 hospitals are federally-run, including by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. The federal government has a valuable role to play in incentivizing climate adaptation in hospitals by providing technical support, funding, and—above all—leadership.

Here are some immediate actions the federal government should take:

- The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) must issue an emergency standard to protect workers from COVID-19. That’s important anyway, for all sectors. But such a standard becomes doubly important as healthcare facilities face possible staffing shortages ahead of, and during, hurricanes or other weather disasters.

- Health and Human Services and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) should expedite the production and dissemination of technical guidance for hospital administrators and other healthcare providers who face the dual threat of COVID-19 and climate- and weather-related disasters. FEMA’s fact sheet on siting temporary hospitals and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s interim guidance on emergency cooling centers are a good start.

- The National Institutes of Health should partner with academic or private sector modelers to assess how hurricane, flood, or fire evacuations could facilitate the spread of COVID-19, affect hospital capacity, and contribute to future waves of infections. Existing tools, such as the IHME COVID-19 model, do not take weather-related disasters into account.

Over the longer term:

- Congress should help create a national culture of climate resilience by directing federal health and emergency management agencies to strengthen and implement their climate adaptation plans. As some readers may recall, one of President Trump’s earliest actions was to revoke an executive order that would have helped prepare the nation for this moment. Congress can ensure the continuity of climate planning by turning an updated version of the executive order into law.

- Congress should increase funding for the Hospital Preparedness Program, the only federal support for emergency preparedness and response in healthcare systems. Funding for the HPP has declined 60 percent since 2003.

- OSHA should expedite its review and update of its existing emergency response and preparedness standards. Many of these federal workplace standards are decades out of date, are not comprehensive, and do not consider the effects of climate change.

Hospitals are central to our communities. They help sick people get better and healthy people stay well. They create jobs, sometimes serving as the single largest employer in a community. And during disasters, they may be the only place for miles around where survivors can get a meal or a place to sleep.

It’s in our national interest to ensure healthcare facilities can keep their doors open and their patients safe—no matter what pandemics or climate-related threats barrel our way.