New York City residents gathered yesterday to speak up for clean water. They came to a hearing room downtown, with a 27th-floor view of Manhattan's concrete jungle, to demand bays, rivers, and creeks that are, quite simply, clean enough to touch.

That's not so much to ask, in the biggest city in the most prosperous nation in the world. But, 43 years after the Clean Water Act promised "fishable, swimmable waters," here we are. New Yorkers of all ages, genders, ethnicities...and all boroughs. Swimmers, kayakers, and canoers. Parents, grandparents, and teachers. And just plain neighbors of urban waterways.

They all gathered to call on New York State -- and, by implication, New York City -- to clean up our waters. By their own account, they came to speak for those who already use the city's 500-plus miles of coastline for water-based recreation and fishing, those who wish to use these waters but don't for fear of pollution and, as one speaker emphasized, for future generations of people (and, literally, for the birds) who cannot speak for themselves but whose world will be shaped by the decisions we make today. (Scan down this blog for some highlights of the speakers.)

The gathering was a public hearing convened by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC). The state invited comments on a proposal to "upgrade" the state's water quality standards. The proposed rule would declare that all of New York City's coastal waters and tributaries must be kept clean enough for people to enjoy a full range recreational and educational activities -- including swimming, wading, kayaking, canoeing, fishing, and youth environmental education -- without fear of returning home with rashes, pinkeye, diarrhea, or worse.

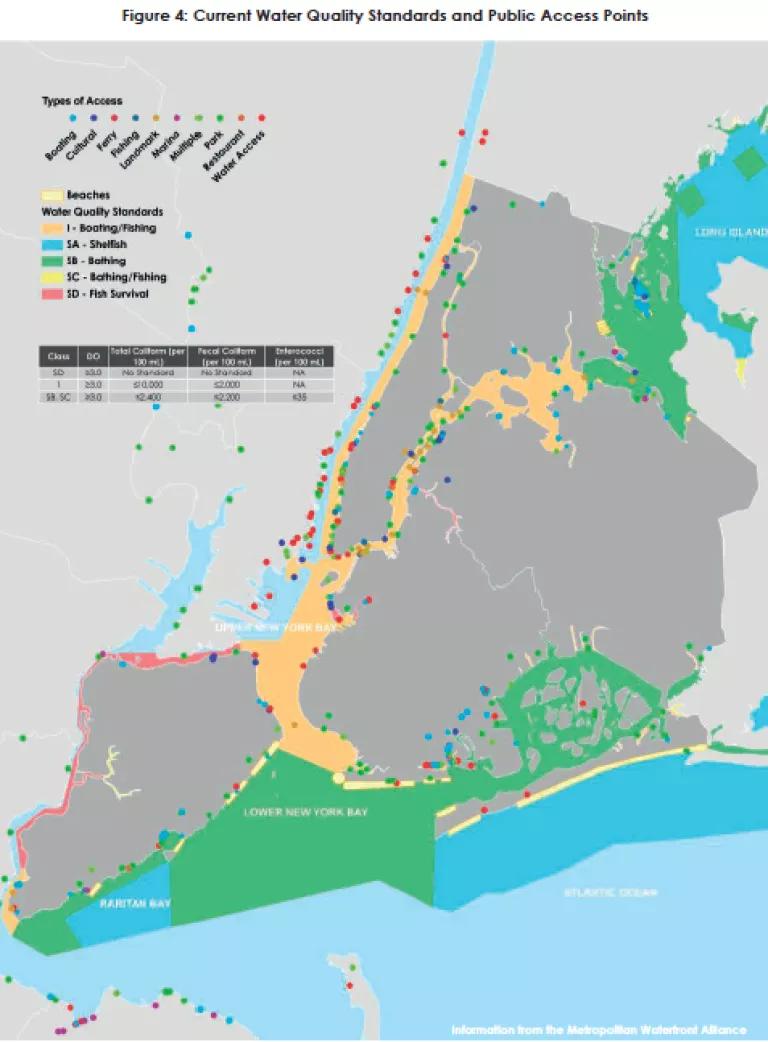

The proposal would enhance legal protections for the Hudson River (south of the Bronx), Harlem River, Bronx River (tidal portion), East River, Flushing Bay, Newtown Creek, Gowanus Canal, Jamaica Bay tributaries, Kill van Kull, and Arthur Kill. All of the waters highlighted as orange or red on the map below.

Unlike other waters designated by law for "primary contact" recreation -- such as the waters colored tuquoise, green, and yellow below -- these waters are currently protected only for fishing and/or "secondary contact" recreation that involves incidental contact with the water.

As I'll explain further below, while DEC's proposal is a major step in the right direction, it appears to suffer from a big loophole that could keep it from achieving the Clean Water Act's "fishable/swimmable" goal.

There's a simple reason DEC's "water quality standards" are so important. Stronger standards for these waters will drive more ambitious cleanup plans, which New York City must develop and implement under the Clean Water Act. Pursuant to a state enforcement order, New York City is developing plans to reduce raw sewage overflows, the greatest ongoing source of pollution (nearly 30 billion gallons per year). Under another permit that DEC will soon issue, the City will also need to develop a plan to reduce polluted runoff from streets, sidewalks, industrial sites, and other surfaces, where pollution like motor oil, toxic metals, pesticides, fertilizers, pet waste, and litter are washed by rain into local waterways, via storm sewers.

As I've written before here, the city has started to implement solutions like green infrastructure, but still has a long way to go and needs to set its sights higher.

By law, DEC must approve -- or disapprove -- all of the City's cleanup plans based on (among other things) whether they reduce pollution enough to meet the applicable water quality standards. The higher the standards, the more pressure there is for the City to ramp-up its cleanup efforts. So the legal standards matter -- a lot.

To be sure, as compared to past decades, water quality has already improved dramatically in New York harbor and other urban waters around the country. On a clear day, thanks to forty years of the federal Clean Water Act and billions of dollars in federal, state, and local investments in sewage treatment and other pollution controls, the water here is typically is clean enough to touch. As a result, many thousands of New Yorkers are able to enjoy the waterways that comprise largest open spaces in this city of islands, but which were once considered virtually off-limits because they were so dirty.

Yet, when it rains and often for several days afterwards, water all around the city still becomes fouled with raw sewage and polluted runoff, making many waterbodies unsafe for contact on scores of occasions each year.

That's why dozens of people -- I counted at least 50 filling the hearing room, not including agency staff -- came in the middle of the workday to demand that we set our sights higher and restore the clean and healthy waterways we deserve.

Here are some of the highlights. DEC officials heard from:

- Members and coaches of "Dragon Boat" canoeing teams, representing the thousands of people who paddle regularly each summer in Flushing Bay, near LaGuardia Airport. One after another, they told of how they contend with "fetid" and "filthy" water. They often "accidentally inhale it or swallow it - not a pleasant experience," said one. Boats also sometimes tip over, they noted. Others spoke of contracting infections and rashes "because of contact with the water"; some have even ended up in the emergency room, while another said she has been "trying to cover myself from head to toe" to protect herself. But they all keep coming back because "Flushing Bay is our home" and there is "nowhere else for us to go to paddle." One coach spoke of the 100+ students he brings out each year, for the last 16 years, and spoke proudly that he and others had "the passion to be here today" to speak out for clean water. Members of a Dragon Boat team comprised of cancer survivors emphasized that "this can be fixed" and that "we need government to do something about it." Together, many of the Dragon Boat teams recently formed an organization called "Guardians of the Bay," to do citizen water quality monitoring and to fight for clean water.

- Members of the Gowanus Canal Community Advisory Group, representing those who live near, and recreate in, the notoriously polluted water body in Brooklyn. They are fighting for both a cleanup of hazardous waste piling up for decades at the bottom of the canal and an end to the ongoing dumping of raw sewage when it rains. Like all of the other speakers, they supported an upgrade to "primary contact" protections. They also talked about how, with the increased flood risks associated with climate change, the dangers of polluted water in their neighborhood extend even to those who have no intention of going in the canal -- in extreme storms like Superstorm Sandy, the canal is now prone to flowing over its banks, bringing sewage and other waste with it into their streets and buildings.

- The ecology director of the Bronx River Alliance, which has been working for years to restore a forgotten urban river to a habitat for fish and wildlife, a recreational amenity, an environmental education resource for underprivileged youth, and a source of community pride. She spoke of how area kids are in the water frequently, despite the hundreds of millions of gallons of sewage mixed with polluted runoff that flow untreated into the river each year. And she emphasized that the state must ensure water is clean enough for people to use on the day that they're using it and where they're using it -- in contrast to the current practice of measuring compliance with standards based on an "average" of a few random samples taken over the course of a month (often when it hasn't been raining), and are often taken far from the places where people access the water.

- A National Park Service biologist, who does water quality sampling at Gateway National Recreation Area in Jamaica Bay (pictured below, in Queens and Brooklyn, with the Manhattan skyline in the background). "I test the water and I can tell you Jamaica Bay is very bad" after it rains, he said. He emphasized that the Park Service, and many others, are working to give more urbanites a chance to experience nature close to home, in a stunningly beautiful (but ecologically imperiled) federal wildlife refuge that is accessible to millions by subway.

- A representative of the Harbor School (a marine-themed public school on Governor's Island, just off the southern tip of Manhattan) and its non-profit Billion Oyster Project (which aims to restore a flourishing oyster population to the harbor, through a partnership of schools, businesses, nonprofits, and government agencies). He described how their program brings schoolchildren into the water (and under it, in SCUBA gear!) for oyster restoration and environmental monitoring projects from April to November every year.

There were also representatives of regional environmental organizations, including NRDC and our partners such as Riverkeeper. There was a leader of the New York City Water Trail Association, which promotes human-powered boating throughout the city; a representative of the Citizens' Advisory Committee to EPA's NY/NJ Harbor Estuary Program, which also submitted written comments; and one from Newtown Creek Alliance, which faces similar issues as the Gowanus Canal community.

Many of the speakers (including myself) were also associated with the Storm Water Infrastructure Matters (SWIM) Coalition, which represents scores of organizations dedicated to ensuring swimmable waters around New York City through the use of green infrastructure practices in our neighborhoods.

We all called for fishable / swimmable waters, to fulfill the promise of the Clean Water Act.

I noted above that the state's proposal appears to have a major loophole. It's unclear whether that loophole is intended or unintended. Either way, we're pushing hard for the state to close it. Here's why:

To provide the legal protections necessary to fully protect public health, the City's waters need to be assigned a "designated use" of "primary contact" recreation. Primary contact means activities with a likelihood of getting significantly wet -- not flecked with a bit of spray on the deck of a pleasure boat, but genuinely wet, from things like wading, paddling in an open canoe or a kayak, or swimming. Wet enough that, if there's sewage in the water, you run a significant risk of getting sick, like the Dragon Boat team members who testified today.

With a "primary contact" designation comes the protection of EPA's "recreational water quality criteria," which set maximum levels of enterococcus bacteria intended to ensure that sewage and other sources of pathogens (like pet waste washed off of streets and sidewalks) don't pose significant health risks. (EPA's standards themselves should actually be stronger, in order to meet that goal, as NRDC and our partners have emphasized. But that's a story for another day, as even the EPA standards would be stronger than what DEC is currently proposing.)

The concern about DEC's proposal, expressed by so many at the hearing, is that it doesn't actually change the designated use to primary contact, which would require use of the EPA standard. Rather, DEC's proposal relies on a weaker standard, based on outdated science, which uses "fecal coliform" bacteria levels as the measure of cleanliness. While fecal coliform sounds plenty gross -- and it is -- for at least three decades scientists have recognized that enterococcus bacteria is actually the best indicator of human pathogens in the water. Indeed, for New York City waters currently designated for primary contact recreation, DEC's standards already use an enterococcus standard. There's no reason not to do the same for the rest of the city, to provide an equal level of protection.

So here's the bottom line: DEC's proposal takes a big, albeit long-overdue, step forward by declaring -- for the first time for the many water bodies listed above -- that "the water quality shall be suitable for primary contact recreation." But, as the proposal currently stands, it's a second-class citizenship for those waters and for the people who wish to enjoy them. By using outdated science to define "swimmable" (i.e., primary contact) water quality, DEC offers half a loaf when New Yorkers are hungry for - and the Clean Water Act requires - a full loaf. DEC should move forward without delay, with a fully-baked standard that gives New Yorkers and their environment all of the protection they deserve.

For more on how DEC should improve its proposal, see the SWIM Coalition's website here.