A Fifteen-Year Chronology of the Casino Controversy

in New York State

Last year New York State saw some huge environmental wins: the ivory trade crackdown, the expansion of solar and other renewable energy, New York City's move to get rid of foam containers, and, of course, the momentous fracking ban.

But there was another victory: the authorization to build new casinos across New York State.

Sure, on its face the decision to greenlight the construction of four new casinos doesn't sound like much of an environmental success story. Indeed, putting aside any questions of whether there would be economic or job-creation benefits from casinos, or even the viability of new gambling halls in an already saturated Northeast market, few would argue that building casinos is an environmental plus for any part of the state.

But if we view the December 17th announcement historically, it is easier to see how the Cuomo Administration's casino strategy prevents the considerable environmental damage that the casino plans of at least three previous Governors would have brought to New York's sensitive Catskill region. In addition, the state also turned away several recent casino proposals that would have jeopardized other environmentally important areas of New York--including Sterling Forest.

By saying no to casino clusters, the Cuomo Administration is also helping to keep the path open for further sustainable economic development--for farms and food, wine and beer making, and clean energy--in the Catskills, the Hudson Valley, and other key regions of the state.

2000-2005: The Five-Casino Catskill Plan

To understand why the recent casino decision is good news for New York's environment, it's helpful to have a little background on some of the early ill-conceived casino proposals in the state and the special nature of the areas that were slated for gaming complexes.

One of those special areas was the Catskills region, centered roughly 100 miles northwest of Manhattan and home to the 700,000-acre Catskills Park, one of the first state parks in the nation and the oldest east of Mississippi River. The impetus for such early preservation efforts is clear to anyone who has visited the region. Characterized by its breathtaking vistas and mountainscapes, it is a hub for wildlife and outdoor recreation, and a world-renowned destination for trout fishing. The Catskills also encompass hundreds of family-owned farms and six massive reservoirs that supply drinking water to roughly nine million people (almost half of the state's population), making it is one of the most important watersheds and foodsheds in the state.

But despite the area's natural wealth and beauty, the region has been economically depressed since the decline of the Borscht Belt resorts. This vulnerability opened the door to several decades of failed casino proposals for the region. For example, one large casino at the Monticello Raceway came very close to reality in 2000, only to be stymied in part by fighting among competing developers and the St. Regis Mohawks, the Indian Tribe that would have run the gambling complex.

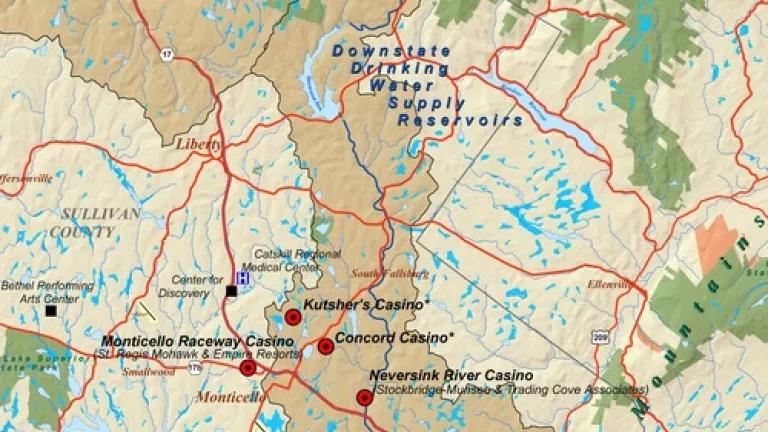

However, in 2001, in the wake of 9/11, Governor George Pataki pushed through a new statutory provision in Albany to provide him clear authority to approve three large-scale Indian casinos in the Catskills. And in February 2005, he expanded on this scheme with a plan to cram in five Las Vegas-style casinos along a roughly 10-mile stretch of Route 17 in the Catskills' Sullivan County.

According to Governor Pataki's own estimate, this plan would have attracted an estimated 31 million gamblers per year to the quiet Catskills region--putting it then in the ballpark of Atlantic City (34 million) and Las Vegas (38 million). By comparison, today there are only 2.5 million visitors per year in the Catskills, mainly for outdoor recreation.

At that time, the New York State Constitution generally prohibited casino gambling. So, to overcome this hurdle, the Pataki Administration sought to use a rarely used provision of federal law that allows Indian tribes--even ones located in different states--to build casinos on so-called "off-reservation" Indian lands.

Threats to the Neversink River, Shawangunks, and the Catskills

Of the five proposals, the most egregious from an environmental standpoint was an off-reservation proposal to build a massive Indian casino directly along a one-mile stretch of the Neversink River--one of the most important river ecosystems in the country, home to globally endangered mussels, and considered to be the birthplace of American fly fishing. Under the plan advanced by the Stockbridge-Munsee Tribe of Wisconsin, the Neversink casino would sit on a 333-acre lot and would include a nearly 600,000-square-foot casino, with 22 restaurants and fast food outlets, and 9,500 parking spots.

Another massive Indian casino proposal, by the Oneida Tribe of Wisconsin, would have permanently marred the viewscape and integrity of the Shawangunks--a majestic mountain ridge in Ulster, Sullivan, and Orange counties that is one of the most important biodiversity sites in the Northeast and an internationally famous rock climbing mecca.

This five-casino Catskill plan had deep and broad support from state and local elected officials, as well as some of New York's biggest unions. (See a 2005 placard prepared by gambling interests in support of the five-casino Catskill Plan below.) Indeed, the only real opposition at that time was the environmental community, some small anti-gambling groups, and several New York Indian tribes. One top Pataki strategist even told NRDC directly that the five-casino plan was a "done deal."

NRDC didn't--and does not--take any position on gambling or off-reservation casinos. But with our state and local partners--including the Sullivan Alliance for Sustainable Growth, Orange Environment, Theodore Gordon Flyfishers, Adirondack Mountain Club, and the newly-formed Catskill Mountainkeeper--we strongly opposed this five-casino proposal. We raised concerns that a casino zone of this scale would have significant environmental impacts in the Catskills, including increased traffic congestion, impairment of air and water, and ancillary sprawl development.

If advanced, we said, this Catskills casino plan would forever change the natural beauty and rural character of the region.

To protect the Catskills, NRDC and our allies deployed an array of advocacy strategies to fight this plan, including commissioning a traffic study by highly respected consulting firm Sam Schwartz Engineering. We then ran ads on the radio and billboards along Route 17 highlighting the nightmare traffic problems multiple casinos would bring to Sullivan and Orange Counties.

Another effective weapon was to take aerial photos of the proposed casino sites and show them to the Governor's office and other key Albany decision-makers--most of whom had never visited or seen the land parcels. A New York Times editorial later described these photos--two of which are pictured above--as "heavy artillery" that gave "a vivid picture of the damage casinos could inflict on what is now a largely untroubled landscape."

2006-2010: Governors Spitzer and Paterson Try Their Hand

Thanks in significant part to our well-organized opposition, the five-casino scheme largely dissolved by the end of 2005. However, serious proposals to build as many as three casinos in the Catskills continued for much of the next decade.

After he took office in 2006, Governor Eliot Spitzer pushed hard for necessary federal approvals--from the U.S. Interior Department's Bureau of Indian Affairs--for the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe to once again try to build a casino at the Monticello Raceway. Indeed, by his own account, this was one of only two requests he made directly to President Bush in a meeting in 2007.

But NRDC and several key allies went to court to stop this casino on the grounds that a required federal environmental impact statement had not been completed to assess the threats of this massive development as well as the cumulative impacts of all the casino proposals still hanging over the region.

In the end, a combination of the environmental outcry and the Bush Administration's resistance to siting off-reservation casinos sunk this proposal.

Not to be outdone, in 2010, Governor David Paterson scrambled to get necessary approvals for the Neversink Indian casino in the final days of his controversial Administration--only to be rebuffed by federal officials several months later for some of the same off-reservation casino siting concerns and as a result of a renewed environmental backlash.

2011-2014: Governor Cuomo Chooses a Different Casino Path

When Andrew Cuomo took office after Gov. Paterson, he embarked on a different approach to building casinos. Instead of continuing to push for off-reservation Indian casinos that required difficult federal sign-off, Governor Cuomo sought a bold course of action: amending the provision in the New York State Constitution that prevented the operation of full-fledged non-Indian casinos--that is, casinos with poker, roulette and other table games, as opposed to ones with only video slots or bingo.

The result of this strategy came in November 2013, when New York voters approved a public referendum that changed the State Constitution to allow up to seven full-fledged casinos around the state. These seven casinos are in addition to the current nine state-authorized "racinos," which have combined video gambling and horse racing, and five full-fledged Indian casinos that reside on federally approved reservation land.

A separate state gambling law hammered out by Cuomo and the Legislature in 2013 authorized the State Gambling Commission to issue licenses for four of the seven new constitutionally sanctioned casinos in selected upstate counties of the state. No additional licenses, however, could be issued for at least seven years, until 2020. After that date, the Legislature will presumably authorize the siting of the three final casinos now allowed by state's Constitution--some or all of which are likely to be in New York City, Westchester, or Long Island. Finally, as a partial consolation to downstate politicians, the complex 2013 gambling law allows two new 1,000-machine video slot parlors to be built on Long Island before this seven-year waiting period is over.

On December 17, 2014, the same day the Cuomo Administration announced its fracking ban decision, the New York Gaming Facility Location Board, a creation of the New York State Gambling Commission, revealed that it was selecting three applicants--out of a total of 16--to build large casinos in three pre-determined upstate regions of the state.

The three casinos sites were located in the Town of Thompson in Sullivan Country (Catskills/Mid-Hudson region), on the Mohawk River in the City of Schenectady in Schenectady Country (Capital region), and in the Town of Tyre in Seneca Country (Eastern Southern Tier/Finger Lakes region).

In its December 17th decision, however, the Location Board stated that it believed a fourth casino "in any of these regions would make it significantly more difficult for any gaming facility to succeed in that region."

Initially, Governor Cuomo said that three casinos was "the right number," but he later shifted his stance after lawmakers and the losing bidders from the Southern Tier region complained that a fourth casino should be built there. In response to a letter from the Governor, the Board announced it would solicit a new round of bidding for a casino in the Southern Tier. Significantly, the Board's Chairman emphasized that "two casinos in the Catskills did not make economic sense."

The end result of these December and January announcements is that no one region of the state becomes a "sacrifice zone" for new large casinos--especially the Catskills. Thus, instead of the five colossal Catskills casinos Governor Pataki proposed, or the multiple casinos entertained by Governor Spitzer or Paterson for that region, the selection committee limited the number down to one.

The Location Board's decisions also spared proposed casinos at several environmentally sensitive sites in the mid-Hudson region. Arguably, the biggest winner was the 21,000-plus-acre Sterling Forest State Park in the middle of the Hudson Highlands region near the town of Tuxedo. This forest is a largely uninterrupted natural area of rugged and dramatic beauty, and forms a significant unspoiled portion of the Ramapo River watershed--which provides drinking water to more than 4.5 million people in New York and New Jersey.

The casino proposal that was rejected (submitted by the developer Genting Americas) called for the construction of a mammoth facility--a 1.4 million square-foot complex with a 1,000-room hotel, a 50,000 square-foot gaming floor, and 7,000 parking spaces--in the heart of Sterling Forest State Park.

Outlook for 2015 and Beyond

Of course, the environmental saga of New York's casinos is not over. The state's environmental review process must still be completed for the three (or four) new casinos before they can be built. And while the Location Board blocked casinos proposed for some of the most delicate lands in New York, this process will likely raise new environmental concerns--and spur new litigation--at some or all of the chosen sites.

For example, the proposed Catskills site at the old Concord Hotel, just outside Monticello, is not a quaint James Bond-style casino parlor. Although the site is not virgin land, it would still include a new 18-story tower, an 86,000-square-foot casino, a nearly 400-room hotel, and an adjacent indoor water park and entertainment village. And at least one powerful constituency near the site has voiced opposition to this complex, at least prior to the final selection.

There will also likely be a new round of environmental (and other) concerns when the Legislature authorizes the final three casinos after 2020.

But for now, after battling the clumping of Catskill casinos with three Governors over the past 15 years, the Cuomo Administration's gambling decisions must be considered a key victory of 2014--and one that opens the door to more sustainable economic development in some of the state's most environmentally rich regions.