New Mexico's Hydrogen Hub Needs Climate Guardrails

New Mexico's hydrogen hub effort must be accompanied by a more comprehensive climate legislation package, which is New Mexico’s best chance to cut emissions and promote long-term economic stability, as well as policy guardrails to mitigate the risks of hydrogen investments.

Hydrogen produced via steam methane reforming at an oil refinery in Commerce City, Colorado.

As federal funding for hydrogen development looms on the horizon, New Mexico is focused on becoming one of the nation’s first hydrogen hubs. Governor Lujan Grisham recently promised to unveil her “Hydrogen Hub Act” in 2022, a bid of her state’s candidacy for a spot among the 4 regional hydrogen hubs to be selected by the Department of Energy. This hydrogen effort must be accompanied by a more comprehensive climate legislation package, which is New Mexico’s best chance to cut emissions and promote long-term economic stability, as well as policy guardrails to mitigate the risks of hydrogen investments.

In certain cases, hydrogen has the potential to support deep decarbonization goals, but it must be nested within a broader climate policy framework. New Mexico needs such a framework to meet its goal of reducing emissions by 45 percent by 2030 (relative to 2005 levels). Fortunately, the state is on the right path: Governor Lujan Grisham recently called for binding commitments to net-zero emissions for each sector of the economy by 2050. These limits, in conjunction with a framework of targeted sector decarbonization efforts, would create demand for technologies like hydrogen within a portfolio of cost-effective climate solutions.

Without this framework, indiscriminately investing in hydrogen as an energy ‘transition strategy’ comes with great risks. At best, hydrogen offers the opportunity to decarbonize the hardest-to-abate sectors of the economy while providing job transitions for New Mexico’s fossil fuel communities. At worst, hydrogen investments that are poorly aligned with climate goals—including those for heating and transport in lieu of more cost-effective and efficient electrification—risk subsidizing a market for methane from a leaking system. Doing so locks customers into a costly energy system while increasing emissions, diverting resources from tried-and-true climate solutions, and perpetuating the harms of fossil fuel infrastructure.

Hydrogen legislation should not displace or delay the climate progress that New Mexico desperately needs. In designing a hydrogen strategy, policymakers should consider the following guardrails to ensure that hydrogen development is climate-driven, economical, and equitable:

- Package hydrogen within a broader deep decarbonization framework that prioritizes existing climate solutions.

- Weigh the long-term financial prospects and risks of blue and green hydrogen.

- Invest only in end-use applications where hydrogen is uniquely suited to the task.

- Enforce a rigorous system of emissions mitigation and monitoring—the first of its kind.

- Center environmental justice and public health protections within planning and development.

1) Package hydrogen within a broader deep decarbonization framework that prioritizes existing climate solutions.

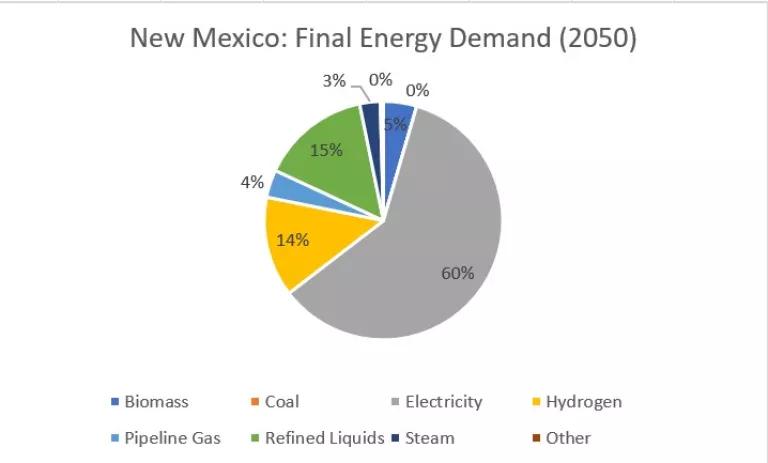

In a study commissioned by NRDC, Sierra Club, and other groups, Evolved Energy Research examined the costs and implications of various pathways towards achieving New Mexico’s climate goal. The results show two-thirds of energy demand being met with electricity, 99 percent of which is generated from renewable resources by 2050. Given the abundance of wind and solar resources, New Mexico’s first investment priority should be in proven and readily-available climate solutions: battery storage, electrification, renewable energy, energy efficiency, and transmission. Common-sense policies can ensure that these technologies reach their full potential; these include a zero-emission vehicle standard, residential electrification solutions like air-source heat pumps, and the acceleration of the state’s 100 percent clean energy target to 2035.

Final energy demand in New Mexico in Evolved's Core decarbonization scenario by 2050.

2) Weigh the long-term financial prospects and risks of blue and green hydrogen.

Not all hydrogen is created equally. ‘Green hydrogen’ is derived from water using renewable-powered electrolysis; ‘blue hydrogen’ is derived from methane and requires carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) technology to reduce the release of carbon into the atmosphere. ‘Gray hydrogen’—the most commonly produced form of hydrogen today—is made from methane without using CCS, resulting in an even higher emissions footprint.

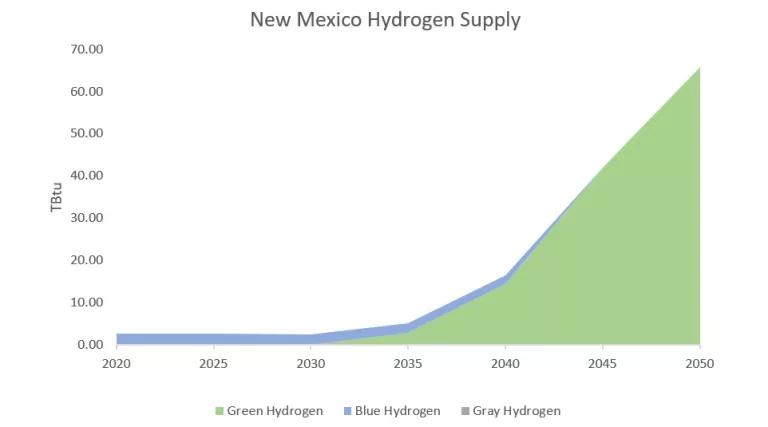

There is a strong consensus that green hydrogen will outcompete blue hydrogen from 2030 onwards in most markets. Green hydrogen offers opportunities for continued cost reductions through deployment and economies of scale. In contrast, the technology underpinning blue hydrogen—steam methane reformation—is largely mature, meaning there is less potential for cost reductions and a higher risk of being undercut by cheaper alternatives. This is corroborated by the Evolved modeling: though the study projects a small deployment of blue hydrogen in the near term, green hydrogen dwarfs supply in 2035 and onwards.

Hydrogen supply in New Mexico from 2020-2050 in Evolved's Core decarbonization scenario.

Given the long lifetimes (20-40 years) of CCS infrastructure, rushed investments in blue hydrogen risk locking New Mexicans into an expensive system for decades, even as cheaper options emerge. Alternatively, these uneconomic assets also risk being stranded, leaving their costs to be shouldered by New Mexicans. Moreover, investing in blue hydrogen as a “bridge fuel” to green hydrogen is a tenuous plan, given that infrastructure for renewable-powered electrolysis is vastly different than building out carbon pipelines and storage basins.

By overinvesting in blue hydrogen and betting against these risks, New Mexico would be gambling with the futures of its workers and their families. The state’s investment strategies must prioritize the long-term stability of its economy and workforce—especially for frontline and energy-dependent communities—over the interests of an industry whose future remains deeply uncertain.

3) Invest only in end-use applications where hydrogen is uniquely suited to the task.

Hydrogen can act as a valuable complement to renewable energy in harder-to-abate sectors but is an inefficient and expensive solution in applications that can be served by direct electrification.

In its core decarbonization pathway, Evolved’s model projects that hydrogen (the vast majority of which is green) meets 14 percent of New Mexico’s final energy demand by 2050. It is deployed in the most challenging sectors to decarbonize—including aviation, maritime shipping, and long-haul trucking—where there are technological barriers to electrification. Outside of these sectors, direct electrification is more cost-effective and efficient than hydrogen, including for light-duty vehicles, residential and commercial space heating, and water heating. For example, heating a home with hydrogen requires up to 6 times more electricity than heating that same home with a high-efficiency heat pump.

Furthermore, hydrogen projects should only be deployed where there is adequate water supply. New Mexico’s water stresses are projected to worsen in light of aridification driven by climate change. Using water as a feedstock for hydrogen on top of the consumption footprint of fossil fuels may threaten New Mexicans’ access to already scarce water resources.

4) Enforce a rigorous system of emissions mitigation and monitoring—the first of its kind.

Mitigating the risks of blue hydrogen requires technologies and systems of accountability that do not exist at scale today. To deliver on climate benefits, hydrogen legislation must ensure the following:

Policymakers must have zero tolerance for methane leakage from hydrogen production. Failing to profoundly reduce methane leakage and emissions from oil, gas, and hydrogen operations would not only undercut the benefits of hydrogen but have outsized impacts on the climate itself. Methane is a highly potent greenhouse gas: its “warming potential” is over 80 times that of CO2’s in the first 20 years after it is emitted. This means that any additional methane released into the system, even in the near term, compromises the world’s ability to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. Methane leaks are difficult to detect and prevent, and methane pollution from oil and gas production in the Permian Basin—the largest methane plume ever recorded above the U.S.—has been historically underestimated. This highlights the need for policies that specifically and robustly target methane emissions at the state and federal level, in addition to existing waste and ozone rules set by the Oil Conservation Commission and Environmental Department respectively.

Immediate methane reductions will be critical even for New Mexico’s campaign to receive funds for hydrogen development. Given heightened awareness around methane’s potency, the extraordinary levels of methane leakage from the Permian basin risk disqualifying the region from hydrogen hub selection. New Mexico’s leaders cannot waste another opportunity to adopt rigorous emissions limits on a selection bid that may fail.

Carbon capture and sequestration must be proven to be technologically feasible, effective, permanent, and economical. To be considered “low carbon”, blue hydrogen projects must meet or exceed a carbon capture efficiency of 90 percent, which has yet to be achieved at scale. Furthermore, the sequestration of carbon must be permanent, statutorily verified, monitored, and enforced in order to create durable emissions reductions. No jurisdiction has been able to model this yet. Building out the carbon storage and transport infrastructure necessary to achieve these levels of CCS is time- and capital-intensive. Those assets themselves require safeguards to ensure that they don’t exacerbate impacts on surrounding communities already overburdened by pipelines and pollution.

5) Center environmental justice and public health protections within planning and development.

Hydrogen development cannot exacerbate the public health risks and environmental harms already experienced by New Mexico’s most vulnerable communities. The negative impacts of fossil fuel extraction on health, environmental well-being, and economic prosperity have disproportionately fallen on the region’s tribal and frontline communities. The lands of two of New Mexico’s largest tribal reservations, the Navajo Nation and Jicarilla Apache Nation, overlap with the state’s most prolific oil and gas resources. Oil and gas wells impact the homes, schools, and businesses around them; these communities have long borne the burden of fossil fuel pollution without having access to its benefits.

Even if blue hydrogen successfully mitigates climate impacts, localized health risks will persist. Blue hydrogen production and combustion still run the risk of creating smog and releasing hazardous air pollutants (HAPs), both of which are known to cause chronic and life-threatening health effects.

Policies supporting hydrogen development should consider historic inequities by engaging with affected communities, mitigating health impacts, respecting tribal sovereignty, and supporting an equitable transition to a clean hydrogen workforce. Unless environmental justice is embedded in their very design, hydrogen development policies risk perpetuating the systemic injustices experienced by New Mexico’s most vulnerable communities.

New Mexicans deserve climate policies that will protect their health, well-being, and financial futures. Hydrogen is not, by itself, a comprehensive solution to New Mexico’s clean energy transition. It must not distract investments, attention, or resources towards proven, readily-available and cost-effective climate solutions. Through thoughtful policy decisions, we can design a hydrogen agenda that is complementary to the clean, renewable-powered system that we need to achieve our climate goals.