Leaders of nearly 200 nations are in Paris right now working hard to negotiate an international framework to address climate change. Success will necessarily require decisive and sustained efforts to clean up power plants, cut carbon pollution from vehicles and industry, make cars, buildings and homes more efficient, and rapidly scale up production and use of clean and renewable energy. But a new report from Chatham House offers policymakers a new and additional tool in the fight: changing diets.

Here in the United States, we eat a lot of meat. According to the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), in 2013, US meat consumption peaked at nearly 200 pounds per year per person. Roughly half of that was red meat.

Our meat-heavy diets are linked to myriad health problems, from obesity to heart disease and diabetes. Most recently, the World Health Organization made news when it linked consumption of red and processed meat to cancer.

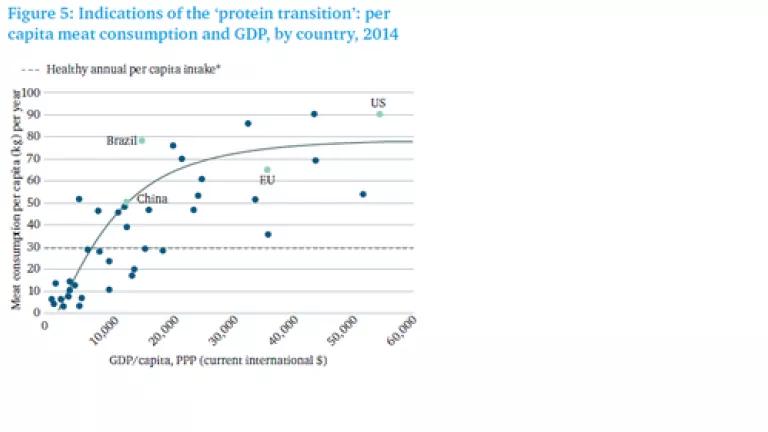

And while the US is among the heaviest meat consumers, this is not a uniquely American problem. According to the Chatham House report authors, global meat consumption has already reached unhealthy levels, and is on the rise. In industrialized countries, the average person is already eating twice as much meat as is deemed healthy by experts and global meat consumption is set to rise by over 75% by 2050.

Source: Chatham House, The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2015

But what many even ardent supporters of climate action often don't realize is that all that meat we eat also comes with a heavy environmental footprint. In particular, red meat from ruminant animals, like cows, sheep and goats, is actually a major driver of climate pollution. Raising these animals requires a lot of pasture land and a lot of grain production--often on land that might otherwise be forested, soaking up carbon from the air. Cows and other ruminant animals, with their multi-chambered digestive systems, are also top emitters of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, through their manure and enteric fermentation (basically, their burps and farts).

That's why, as the report concludes, working on a global scale to replace some meat with other foods will be critical to achieving our climate change goals. The authors estimate that a shift towards healthier patterns of meat-eating could bring a quarter of the emissions reductions the world needs to avoid the worst consequences of climate change. They also underscore the important role governments have in driving dietary change by educating their populations and encouraging reduced meat consumption.

The US government now has the opportunity to do just that. Earlier this year, the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC)--a group of the nation's top health and nutrition experts--concluded that adopting a diet with less consumption of red and processed meat in favor of more vegetables, fruits and other plant-based foods promotes health, and can help Americans reduce their environmental impact, including their impact on the climate. The USDA should now incorporate these science-based recommendations into its 2015 US Dietary Guidelines.

Businesses, such as those in the food service industry, also have a tremendous opportunity to be on the leading edge of encouraging healthier, climate-friendly diets by shifting away from red meat-heavy menus and offering more plant-based foods.