We're losing Antibiotics of Last Resort: NRDC's Analysis Unveils the Global Spread of Drug Resistance

Every week seemingly brings new evidence that we are overusing and on the verge of losing the effectiveness of life-saving antibiotics. The latest story to emerge was that discovery of a new form of bacterial resistance to colistin that can be easily shared between bacteria. Scarier still is that resistance to this critical antibiotic has spread globally.

Colistin is a drug of last resort which can save a patient's life when faced with a multidrug resistant infection. The gene that gives bacteria resistance to colistin ("the colistin gene"), it turns out, is now more mobile and easily shared between bacteria, and has now been widely detected in meat, on animals and in people in many different countries.

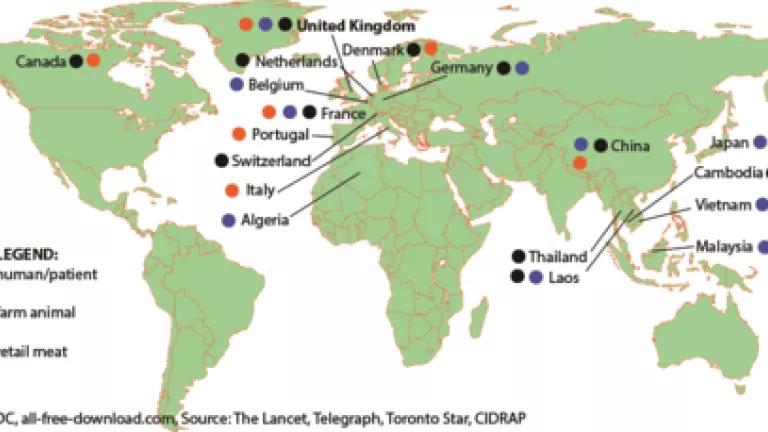

What our new analysis maps, below, is that the list of countries across the world continues to grow, showing how this resistance gene has spread globally in food, animals and humans - from farms to communities, or vice versa.

What We Know

In November, Chinese scientists first published their discovery of the colistin gene (mcr-1) in bacteria in pigs in slaughterhouses, in pork (as well as in chicken) purchased from markets, and in human patients. Almost immediately, other scientists around the globe started checking for the colistin gene in their own collections of bacteria - i.e. bacteria that had already been collected from farm animals, meat, or human patients. In microbiology, as in life, you don't always know what you've got until you specifically look for it.

Above is a map showing as of January 15th where the colistin gene has now been detected--in several countries and in all kinds of samples--from food animals, from meat, and from humans. (Tunisia, Peru, Bolivia and Colombia have been mentioned, but are yet to be confirmed).

And because the colistin gene was detected more often in animals than in people, the authors of the original study say it is likely that this form of colistin resistance originated in animals and spread to people.

Here's what we know:

- The colistin gene has been found both hanging around in a healthy person's gut, as well as in bacteria infecting especially vulnerable patients (children, elderly). That colistin gene has been detected in E. coli bacteria found in water, in a slaughterhouse, on workers (boot swabs) and on pigs, chicken, and cattle - on the animal and/or on the meat.

- The bacteria carrying this gene (and resistance to colistin) don't respect borders. They are moving across national boundaries either as passengers on international travelers, or in traded meat products.

- Bacteria can collect resistance genes and splice them together on strands of DNA that can move around between bacteria. When a bacterium acquires one of these pieces of mobile DNA with many resistance genes, it can transform bacterium from one posing little threat to a potentially lethal superbug that resists treatment by multiple antibiotics.

- One patient in Switzerland was infected with a multidrug--including colistin--resistant E. coli bacterium that could not be treated with almost any drugs of last resort. The bug had collected a ton of resistance genes along the way, including one for an antibiotic normally reserved for veterinary medicine, called florfenicol. This shows that bacteria that are infecting people are collecting resistance genes both from farms and from hospitals.

U.S. Outlook

We just don't know if the colistin gene has showed up in the US. While colistin isn't currently in use (as far as we can tell) in U.S. livestock production, other antibiotics in the same class are used. According to the FDA, they've tested almost 3,000 Salmonella bacteria for the gene and have come up with nothing.

Curiously, the FDA is not doing as much testing for this dangerous resistance as it could. The agency has only tested 76 of the E. coli bacteria in its collection despite the fact that the vast majority of colistin genes detected globally thus far has been detected in E. coli (although it's also been found in some Salmonella and Klebsiella). Yet, we know that FDA has compiled samples of thousands of E. coli bacteria through their 12 years of grocery meat testing. FDA is mum about whether it will be testing for the colistin gene in those isolates.

To Stop the Spread, We Must Stop Overuse in Livestock Production

More than 70 percent of medically important antibiotics sold in the U.S. are sold for livestock-- often for routine growth promotion and disease prevention in animals that are not sick. Leading medical experts, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and World Health Organization, warn that this practice causes bacteria to evolve and become resistant to the drugs we rely on them to treat them. And those drug-resistant superbugs can then spread to humans via the water we drink, the air we breathe, and the food we eat.

Two million Americans get sick from drug-resistant bacteria annually, and more than 23,000 die, according to conservative estimates.

While colistin itself is not used in livestock production here in the U.S., it is widely used abroad. And U.S. farmers commonly use other antibiotics that are often prescribed to treat the same illnesses as this drug of last resort--fueling resistance to other possible treatments that doctors would typically turn to first.

Several government reports last year called for reductions in antibiotic use, including in food animals. Most recently, a report from former Goldman Sachs economist Jim O'Neill, commissioned by the UK government, was issued.

That report calls out the critical need for nations to set numeric targets, to ensure that antibiotic use actually goes down. Admitting that there isn't one silver bullet, the authors write that each country should be given the ability to identify their own way to meet that goal. In fact, we've seen this same strategy work in countries like the Netherlands and Denmark.

That's not happening here in the U.S. While last year's White House launch of a national strategy and action plan to Combat Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria garnered lots of attention, it failed to set any targets for reducing antibiotic use in livestock. That lies in stark contrast to clear goals on use reduction in human medicine. Perhaps it's no surprise then that the latest federal report on antibiotic sales in livestock demonstrates continuous increases, up 23% since 2009 to 2014.

We should be moving forward, not backward. To get there, we need federal limits on the use of any antibiotic on animals that are not sick, regardless of the label attached to such use.

Our analysis provides a crystal clear example now of how antibiotic use in livestock and human medicine are intertwined and translate into a very real public health threat. We cannot afford to keep waiting for action--we need urgent action to curb unnecessary antibiotic use in animal agriculture to save our miracle drugs and the lives that depend on them.