Wildlife Corridors Crucial for California's Biodiversity

The Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, over the 101 Freeway in western Los Angeles County, is the world’s largest wildlife crossing. But why does habitat connectivity matter?

This coming Earth Day, April 22, Californians will celebrate the groundbreaking of the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, the world’s largest wildlife crossing over the multi-lane 101 Freeway in western Los Angeles County, clocking in at 210 feet long and 165 feet wide. The wildlife crossing will be surrounded by an acre of native vegetation and will also include a sound wall to help act as a sound and light barrier from the freeway for wildlife.

But why mark this momentous occasion? And why does habitat connectivity matter?

Benefits of Wildlife Corridors and Crossings

In southern California, as in many other areas of the country, rapid urbanization has broken up what used to be large swaths of wildlife habitat, leaving smaller unconnected areas that don’t provide enough space for animals to hunt or find mates outside of their own family. Wildlife corridors and crossings facilitate the movement of animals across fragmented landscapes to reach food, water, and potential mates, and to adapt to a changing climate. Connectivity is crucial to the state’s efforts to fight the biodiversity and climate crises and its pledge to protect 30% of the state’s lands and waters by 2030. Without the ability to move across landscapes, species cannot thrive in an ever-changing world.

Wildlife corridors and crossings can include both human-made projects like the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, as well as natural wildlife corridors. Riparian corridors, for example, traverse rivers, streams, lakes, lagoons or other natural bodies of water and can facilitate wildlife movement. These natural corridors also provide numerous other benefits such as mitigating flood impacts, improving water quantity and quality, and providing fire breaks. Both human-made and natural corridors can benefit wildlife greatly by connecting otherwise isolated habitat areas to foster increased genetic diversity and improve many species’ chances of long-term survival.

The Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing is one of many planned connectivity pathways that are needed to ensure the sustained survival and well-being of our local wildlife. Here are a few other exciting connectivity projects in California that you should know about.

The Irvine-Laguna Wildlife Corridor

A 20+ year endeavor, this wildlife corridor project is a multi-faceted, six-mile habitat link between mountain and coastal ecosystems in south Orange County. Organizations including Laguna Greenbelt, Hills For Everyone, and Friends of Harbors, Beaches and Parks have led this tremendous corridor effort that eventually will provide a critical linkage to ensure that native wildlife will continue to populate the wilderness area between the coastal wildlands in Orange County and the foothills of the Santa Ana Mountains.

Currently, Laguna’s coastal natural areas are completely isolated from other wildlands, which has rendered the area an ecological island for the native species that live there. This corridor will increase the chances of survival for species like the coastal bobcat and mule deer by expanding their hunting and mating territories.

I-15 Wildlife Crossing, Temecula

As a result of a two-year legal battle to protect the Santa Ana mountain lion (Puma concolor), conservation groups including our friends at Endangered Habitats League and the Center for Biological Diversity reached an agreement with the City of Temecula and a private developer to preserve a 55-acre parcel that protects a critical wildlife corridor for local mountain lions and other wildlife. The I-15 freeway poses a substantial barrier to the movement of mountain lions between the Santa Ana Mountains and the larger Palomar Range, to the point where experts have predicted their local extinction by 2050 as a result of inbreeding due to severed migration corridors and the loss of lions killed in vehicle collisions. The Temecula Creek Wildlife Underpass is an undercrossing for mountain lions and other wildlife to safely cross I-15 so they can reach protected areas on both sides of the freeway. The design strategically phases in appropriate signage, vegetation, fencing, and sound baffles to encourage the mountain lions to safely pass through.

Trinity River Restoration Project

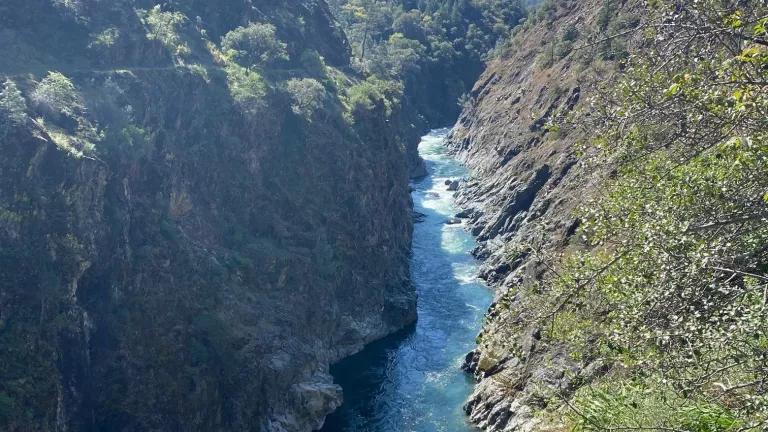

A view of the Trinity River flowing into a mountain valley

The Trinity River, a tributary of great cultural significance to the Yurok and Hoopa peoples, runs through the Klamath and Northern Coast Ranges in northwest California. The path of the Trinity River was altered by goldmining practices and by construction and operation of the Trinity and Lewiston Dams, which blocked the migration passages and decimated habitat for native salmon and other fish, disrupting the lives of the Indigenous river-based communities who relied on the river and held fishing rights to the harvestable fish.

The Trinity River Restoration project aims to revive a healthy migration corridor for both salmon and terrestrial birds and wildlife. The Hoopa Valley Tribe and Yurok Tribe are key stakeholders in the restoration effort and are leading implementation of riparian restoration projects that benefit native salmon and a bevy of diverse wildlife such as martens and eagles. These kinds of projects utilize natural riverine corridors to provide multiple benefits to fish, wildlife and Indigenous communities, who have long stewarded this land in harmony with Nature.

Chollas Creek Restoration Project

Like many urban waterways in southern California, Chollas Creek is a once free-flowing creek turned concrete-lined channel in the City Heights neighborhood of San Diego, an underserved community marked by health and income disparities. After decades of advocacy, community-based groups including Groundworks San Diego are on the way to transforming Chollas Creek into a functional wildlife corridor. The Chollas Creek watershed has a vibrant wildlife population including coyotes, opossums, native birds and rabbits. In the latest phase of the project, the concrete channel will be removed and the banks of the naturalized creek will be planted with native plant and tree species appropriate to the region, providing five acres of native riparian habitat and increased connectivity between the areas of the creek located upstream and downstream. The restoration efforts so far have had many benefits to the surrounding community, such as a tree-lined trail system that connects the southern and northern park-poor neighborhoods and improved flood control and water quality.

These are just a few notable projects in California that show how connectivity between habitats is vital to the biodiversity of plants and wildlife in one of the most species-rich places on earth. In addition to the celebration happening this week, the California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA) will soon be releasing the final Pathways Report that will outline how the state plans to conserve 30% of California’s land and coastal waters by 2030. We support a robust and scientific approach to the state’s 30x30 goals and look forward to reviewing CNRA’s bold commitments and tangible solutions to create a connected system of protected lands and waters throughout the state. Through the 30x30 framework, California has an opportunity to help halt and reverse the current alarming rate of biodiversity loss by strategically conserving lands to connect core habitats and movement corridors for wildlife. As we celebrate the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing this week, we hope to see in the Pathways Report CNRA’s commitment to increase the number of wildlife corridor and crossing projects throughout the state.

Special thanks to my NRDC colleagues Paulina Torres, Dani Garcia, and Jade Nguyen for their contributions to this blog post.