Three Lessons Learned from the Axed Atlantic Coast Pipeline

This is a significant and long-overdue victory for the landowners, community leaders, countless people across three states, and environmental advocates who have fought this project for years.

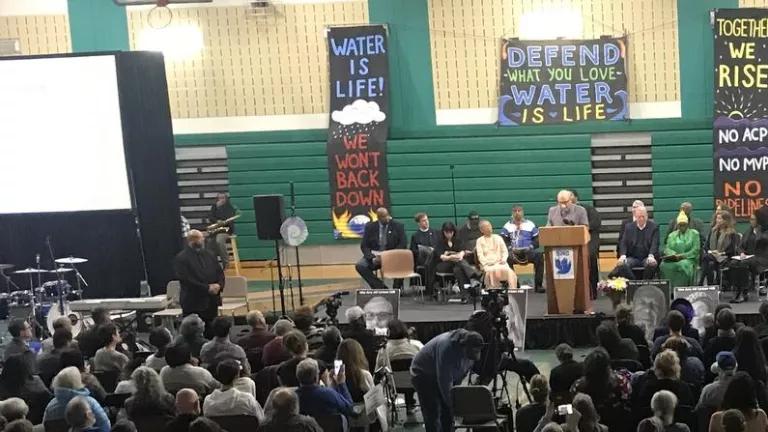

"The Moral Call for Ecological Justice in Buckingham" Event

Dominion Energy and Duke Energy have announced that they are cancelling their beleaguered, billions-over-budget boondoggle, the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. This is a significant and long-overdue victory for the landowners, community leaders, countless people across three states, and environmental advocates who have fought this project for years. The lessons learned from this project go beyond one pipeline. The project provides a perfect case study for the value of local voices and environmental justice advocacy, and for why the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, colloquially known as FERC, must reform its reviews of gas pipeline projects—and stop simply rubber-stamping them.

There are 3 key lessons learned from this case study:

Lesson #1: Local Voices Matter

Representatives for the Atlantic Coast Pipeline waltzed into communities in West Virginia, Virginia, and North Carolina in 2014 with an answer to a problem that didn’t exist. They knew that FERC approves virtually every project brought before it, and they knew that FERC’s approval includes eminent domain authority to seize private property, and would almost assuredly award the developers with a hefty 14% return on their investment. They also knew that challenges to FERC-approved projects were almost never successful, in large part because FERC’s procedural practices, such as its intervention rules and the issuance of so-called “tolling orders” to block judicial review, meant that almost all approved projects evaded meaningful judicial scrutiny.

That led unscrupulous land agents and other company representatives to disrespect private property owners in the path of the pipeline with a sense of entitlement, and to view the project as a fait accompli years before it had completed the FERC review process.

What they didn’t predict was that the local communities would fight back—and with vigor. Groups such as Friends of Buckingham, Friends of Nelson, and others, grew organically along the pipeline route. These groups began organizing summits to teach one another about FERC and the pipeline review process. Had it not been for this grassroots advocacy—begun by area residents rightfully worried that the project could harm their families and communities—it’s likely that the Atlantic Coast Pipeline would already be in the ground and operating. Instead, the project is canceled before almost any construction had begun.

Lesson #2: Environmental Justice Matters

The Atlantic Coast Pipeline was a doozy from the start. The pipeline would have crossed the Appalachian Trail, cut through the heart of Virginia’s viticultural industry and premiere ski resorts, affected numerous waterways and endangered species, and threatened environmental justice communities in both Virginia and North Carolina. For example, pipeline developers proposed to build a compressor station, a facility that literally compresses gas to push it along a pipeline, in Union Hill, Virginia, a community that dates to Reconstruction, was founded by freed enslaved people, and is overwhelmingly African American. Compressor stations pose serious health risks, particularly to already burdened communities, but FERC’s flawed environmental justice methodology remarkably concluded that there were no environmental justice communities located near the compressor station, such that further analysis of disproportionate impacts wasn’t even necessary.

Similarly, project challengers alerted FERC that 25 percent of North Carolina’s Indigenous community lived on or near the pipeline route, but the agency’s faulty mathematical analysis erased the population’s existence. Scientists outlined the methodological flaws, specifically, the failure to account for populations that are small in number but large in percentage, and yet FERC still did nothing.

Communities of color have long borne the brunt of infrastructure development. The Atlantic Coast Pipeline could have been another data point in this disappointing history. But local community efforts raised the profile of environmental justice issues, and despite numerous setbacks, this pressure eventually led the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals to vacate a critical air permit on environmental justice grounds.

Lesson #3: FERC Reform Matters

FERC is authorized by the federal Natural Gas Act to review projects like the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, and may only approve a pipeline project if it is “required by the present or future public convenience and necessity.” This standard incorporates an evaluation of “all factors bearing on the public interest” that “reasonably relate” to the building and operation of a gas pipeline project, including whether there is a “need” for the project, i.e., a market demand.

From the start, the evidence did not support that the Atlantic Coast Pipeline is needed. The developers relied on affiliate, or intra-corporate, contracts as a substitute for actual market demand—meaning that there was never any independent documentation of need for this project. Furthermore, the vanishing demand for gas in the region, coupled with lower cost alternatives like energy efficiency, meant that the pipeline likely would have become a stranded asset, such that Duke and Dominion would have abandoned the pipeline years before the end of its useful life (after seizing and altering hundreds of people’s private property) or delayed switching over to clean energy in a desperate attempt to salvage their gas investments. In both cases, they would have shifted the costs of the project onto captive utility customers.

FERC could have prevented all of this if it worked properly. The environmental and economic risks of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline were apparent throughout the application phase and prompted then-FERC Commissioner Cheryl LaFleur to dissent and vote to reject the project. Instead, the agency applied a rigid and incomplete analysis that allowed the project to squeak through on a 2-1 vote, begin construction, and take private property, while developers lacked several other required federal permits and continued to put forth plans that were struck down in court as illegal.

For over two years, the agency has had an open docket in which it asked for ideas on how to revise and reform its pipeline review process. That docket has largely remained dormant since July 2018. Particularly in light of recent major court losses involving its climate analyses, procedural processes, and the release of the Select Committee on the Climate Crisis’s report, the time is now for FERC reform. Even the agency itself has recognized the need for improvement, particularly in the area of landowner relations and eminent domain. Other critical reforms include:

- FERC should follow its own Certificate Policy Statement and consider “all relevant factors” in determining whether a pipeline is needed, instead of blindly relying on developer-offered contracts as universally sufficient;

- FERC should take its climate analysis responsibilities seriously and incorporate a review of the project’s climatic effects into both its National Environmental Policy Act and Natural Gas Act reviews;

- FERC should no longer accept projects that place unreasonable risks to the environment and to communities of color; and

- FERC should reform its procedural practices so as to ensure that landowners and other community participants can fully and fairly participate in the FERC process.

The Bottom Line

Stopping the Atlantic Coast Pipeline is a major victory, but FERC, and potentially Congress, needs to seize the moment to reform gas pipeline reviews so that they align with the 21st century, the ever-changing gas market, and declining gas demand.

NRDC is up to the challenge. Let’s get to work.