Six of the Worst States to Be a Wolf

To get on a better track towards national recovery, wolves will need proactive and science-driven action by the federal government.

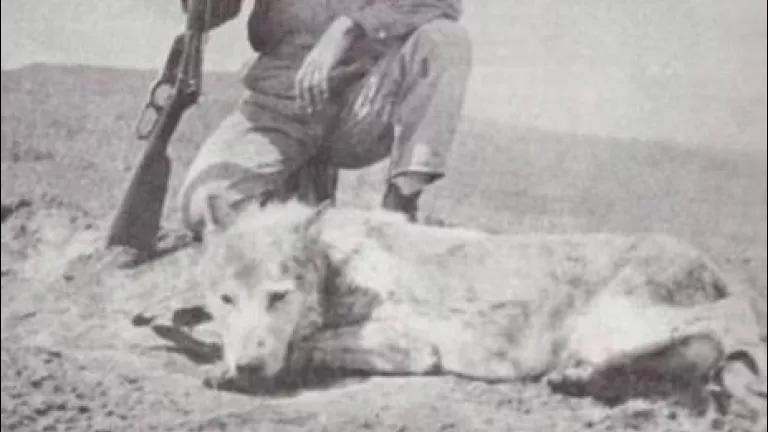

A government trapper stands over the body of "Three Toes"—a wolf with a sensationalized fugitive reputation that was rumored to be the last remaining wolf in the Montana-Dakotas area by 1925.

Credit: Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Gray wolves once roamed widely across the United States, but a centuries-long extermination campaign pushed them to near extinction in the lower 48 states. Since being listed under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) nearly 50 years ago, they have managed to re-occupy some small portions of their historic range but continue to be persecuted based on misinformation and unjustified malice. Today, their path toward recovery is far from stable or assured.

In 2020, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service published a final rule to remove the gray wolf from the federal list of endangered species, thereby fully handing wolf management over to the states after a complicated history of piecemeal regional delisting decisions. Some states have taken a moderate approach to conserve and recover wolves within their borders, but an increasing number of states are politicizing wolf management and adopting archaic policies that reverse decades of wolf recovery efforts.

Supporters of state-sanctioned wolf killing believe aggressive lethal policies are needed to protect livestock and increase game populations, like elk, for hunters. In fact, these justifications are rooted in falsehoods and ignore proven tools for preventing livestock predation. Overall, wolves account for a tiny fraction of yearly livestock losses and elk hunter success rates have been consistently strong. Political rhetoric and scare mongering have eclipsed extensive research showing the value wolves bring to people and ecosystems. Under a lack of federal oversight and recovery planning, state management is proving to be bad news for wolves and conditions are rapidly deteriorating.

Wolves are highly social animals that live in extended family groups, cooperatively caring for their young and hunting in teams.

Here are six states with some of the most hostile wolf management policies in 2021:

Idaho: Beginning in 2011, wolves in Idaho were delisted through a controversial congressional rider. Idaho has long had aggressive wolf killing policies, but a new law allows hunters, trappers and private contractors to kill up to 90 percent of Idaho's wolves using practically any means imaginable, including running over wolves with snowmobiles or ATVs and killing mother wolves and pups in their dens. Some of this will be incentivized using taxpayer dollars.

Montana: Montana’s wolf population stabilized in the decade following their 2011 delisting, but state legislators recently passed a series of bills intending to reduce the population by as much as 80 percent. Wolves will be subjected to tools such as snaring and bounties, with few limitations. Montana’s governor signed off on the new policies not long after he killed a Yellowstone wolf in violation of his own state’s regulations.

Wyoming: Wyoming has historically taken a bare minimum approach to wolf recovery. Across most of the state, wolves can be killed using the most extreme and unethical measures, with little oversight from the state. Wyoming manages wolves as if they are a disposable nuisance.

Wisconsin: During its first state wolf hunt since the 2020 delisting, Wisconsin hunters took to the woods with vehicles and packs of dogs, blowing past the intended cap on the hunt by killing around 218 wolves in just three days. This removed at least 20 percent of the states’ wolf population during breeding season, leaving great uncertainty about wolf reproduction this year. The state failed to consult with the tribes in the region, who have vocally opposed the hunt.

South Dakota and Utah: These states have worked to prevent wolves from becoming established within their borders. South Dakota currently manages wolves as “varmint.” Since delisting, the state has not been coy about their intentions to kill any wolf that shows up. In Utah, the state legislature scandalously steered millions of public tax dollars to an anti-wolf nonprofit to advocate for eliminating federal protections for “out of control” wolf populations—to make it easier to kill lone dispersing wolves that find their way into Utah from neighboring states. Dispersers have played an important role in recovery because they can cover long distances to find new territories or mates. Roaming wolves that enter South Dakota and Utah will now be running the gauntlet.

A gray wolf runs through the shallows of a river.

A better path towards wolf recovery

These states cast a dark shadow over one of our nation’s greatest conservation success stories: gray wolf restoration. Instead of repairing the wrongs of our country’s wildlife extermination campaigns, states are recreating our shameful past by managing wolves as enemies and varmint. Respected scientists, state wildlife management professionals, and even hunting groups are raising the alarm bells over the destructive pattern of states rejecting science and mismanaging wolves.

Wildlife biologists reintroduced gray wolves to Yellowstone National Park and central Idaho in 1995 and 1996, marking one of the first systematic efforts to restore a top carnivore to its native ecosystem.

To get on a better track towards national recovery, wolves will need proactive and science-driven action by the federal government. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service should:

- Reinstate federal protections for the gray wolf

- Develop a comprehensive national recovery plan ensuring that wolves adequately meet requirements of the ESA before delisting

- Ensure decisions are guided by science and experts—not politics

- Exercise oversight to ensure federal dollars are being used by states to support wolf recovery and to incentivize nonlethal coexistence tools such as fladry fencing—rather than wolf killing

As the Biden Administration forges an ambitious path forward to achieve national conservation goals, some states are lurching backwards. This mismatch demonstrates the need for additional leadership and coordination to ensure state-level decisions will also reflect Americans’ positive attitudes towards wolves and the national interest in protecting the environment. It’s time to give wolves the protection they need as a recovering native mammal and a keystone species.

Photo: Pixabay