Flint Map Shows Progress, Reveals Where Lead Likely Remains

New map documents progress of pipe removal program and offers residents critical information to protect their health

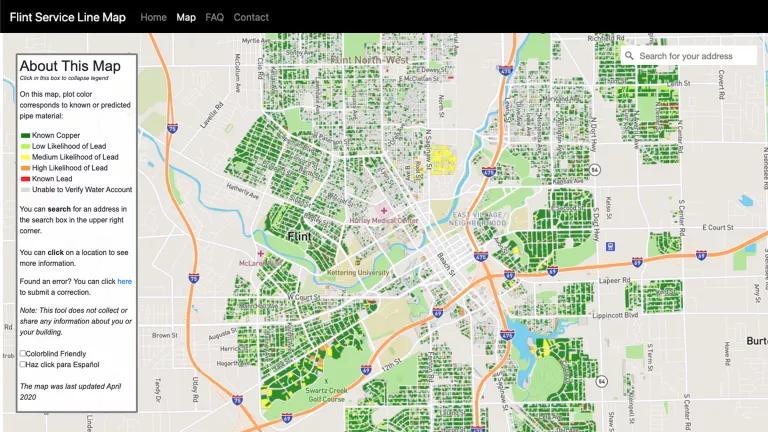

The Flint Water service line map shows the known or likely material of the water pipes at homes in Flint, Michigan, after nearly four years of replacements.

In May of 2019, NRDC’s Flint team and data scientists Jake Abernethy (Georgia Tech) and Eric Schwartz (University of Michigan) were discussing how to best share the information we had about Flint’s service lines—the water pipes that carry tap water from large distribution pipes in the street to individual homes—with the Flint community. The information came from the City of Flint’s inspection of thousands of water pipes as part of a program to find and remove lead.

Flint’s pipe replacement program is the result of an unprecedented 2017 settlement in a lawsuit brought by NRDC and its local partners in response to the Flint Water Crisis. The crisis started when city officials began using the Flint River for the city’s drinking water but failed to follow proper water treatment procedures. This decision resulted in corrosive water flowing for over two years through the city’s distribution system, causing lead to leach from service lines and contaminate the tap water of thousands of residents’ homes. Lead, a powerful neurotoxin that can damage almost every system in the body, is particularly risky to infants and young children, whose developing brains are more susceptible to the metal’s damaging effects.

Lead exposure is preventable. In Flint, the only permanent solution to reducing the health risks stemming from exposure to lead in tap water is to remove the lead pipes. But residents who find out their homes may have lead pipes can take precautions to protect themselves and their families from lead exposure, which is why we needed to share the lead pipe location information not just with the City of Flint but also with the broader Flint community.

“A resident asked if we can make a map to get this information out to his community—can we do that?” Eric asked.

Yes we can, we decided.

And we did, creating the online, interactive Flint Water Service Line Materials Map so that Flint residents can find out the latest information about the known or likely composition of their home water pipes.

The release of the map coincides with the restarting of Flint’s service line replacement program after the project was paused due to Michigan’s COVID-19 restrictions. With pipe inspections ramping back up, the City of Flint is aiming to complete lead pipe replacements this year, which means that time is ticking for Flint residents to grant the City permission to inspect their water service lines and to replace lines that are made of lead or galvanized steel at no cost for residents.

Flint residents can use the Flint Water Service Line map website to find out the current pipe material at their homes, to find the date of last pipe inspection at their address, to link to the City’s inspection permission form, and to access resources for steps they can take to protect themselves and their families if their homes have lead water lines.

From index cards to online map

The idea that any Flint resident would be able to easily access information about their water service lines was a pipe dream in 2015, when it was discovered that the City of Flint had information about water line materials for many of the homes, but that information was scattered across 45,000 individual index cards. Collaborating with the data technology company Captricity, Abernethy, Schwartz, and their colleagues scanned the cards and used artificial intelligence to help make sense of the handwritten and sometimes smudged notes.

But digitizing the available records was only the first step in creating a cohesive and complete picture of the lead pipes in Flint: the index card information dated back to 1910, was often incomplete, and did not provide information for all of the homes in the City. So Abernethy, Schwartz, and their affiliates developed a mathematical model that used all available information about each home in Flint, including the year the home was built and the home’s neighborhood, to estimate the likelihood of that home having a lead water pipe. The City could then use the model to more efficiently find the remaining lead pipes and replace them.

Work to update and refine the model is ongoing. As the City continues its work inspecting homes for lead pipes, it shares its findings with NRDC and Abernethy and Schwartz’s team. That new information is fed into the model, which then updates its estimates for where the lead is likely to remain, which in turn allows the City to focus their inspections on the areas at highest risk for lead. Using the model to more precisely predict where the lead pipes are located means that the City can spend less time and money searching for lead and instead focus its resources on more quickly replacing known and suspected lead lines.

And now, with the publication of the service line map, the model predictions about the water pipe materials bringing tap water into homes across the city is available to residents of Flint for the first time.

The People’s Data Becomes a Map for the People

The map displays the known or likely materials of water pipes across Flint. Clicking on individual homes reveals more detailed information: residents can find out if and when their homes were inspected for lead pipes, and, for homes where lead pipes were replaced with safe copper pipes, when the City of Flint completed that work. Through the map website, residents can also access information about how to protect themselves if they do live in a home serviced by a lead water pipe, how to contact the City of Flint’s service line replacement program, and how to contact the map team.

The Flint Service Line Map is a joint effort helmed by me and Jared Webb, Abernethy, Schwartz, and Ian Robinson of BlueConduit. NRDC lawyers working on our Flint advocacy—Dimple Chaudhary, Sarah Tallman, and Jolie McLaughlin—consulted on the project. The map is the product of our shared belief that residents have a right to know the pipe materials bringing water into their own homes.

We began with a simple mission: To democratize the water pipe data and to put the information into the hands of the people of Flint. We built the map to be user-friendly and accessible to people with diverse abilities and needs. We worked with Flint residents to ensure that we created the best map for Flint. We continue to collect community feedback and implement updates to the map to ensure that we are sharing the data in a transparent and powerful way, giving people what they need to advocate for safe water infrastructure.

The story of Flint continues to be about people demanding safe water and the government being forced to address their disastrous failure in protecting the community from toxic tap water. The clear communication of water pipe information through the Flint Water Service Line Materials Map gives the people a powerful tool in their advocacy efforts.

Flint as a Model

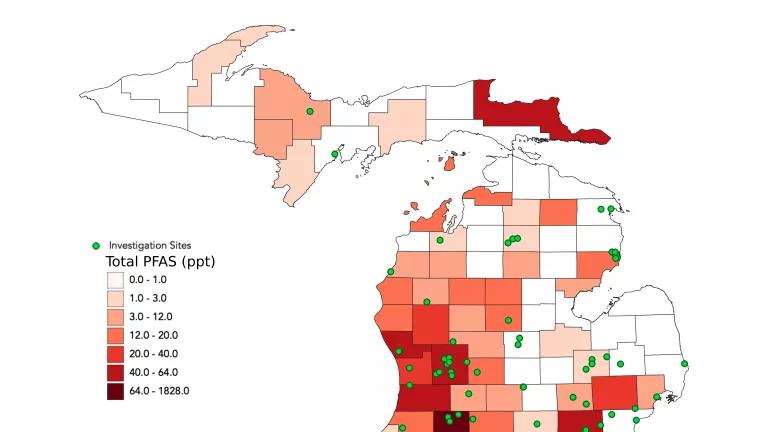

Under the legal settlement won by NRDC and its local partners, the City of Flint is working to find and remove lead water service lines from all Flint homes with active water accounts through its service line replacement program. Beyond Flint, NRDC is fighting to strengthen rules to reduce lead in tap water, championing the robust identification of all service line materials across the country and the replacement of those containing lead.

NRDC’s Mae Wu testified on EPA’s proposed changes to the Lead and Copper Rule.

Proponents of service line replacement programs like Flint’s in other cities often run up against the “time and money” argument: Mandatory replacement of lead service lines “would take decades, cost billions of dollars, and would prevent water systems from allocating their limited budgets to other projects,” complained Angela Licata, the deputy commissioner of New York City's Department of Environmental Protection in her recent testimony on proposed changes to the Lead and Copper Rule.

But our experiences in Flint illustrate that a data-driven approach can help identify the likely locations of lead service lines using all available information, as Abernethy and Schwartz’s model does. This can save time and money in the hunt for lead service lines, allowing cities to focus on digging up the pipes that are more likely to actually endanger the public health. And sharing that information in a transparent and accessible way helps community members assess their personal risk from lead pipes and advocate for safe drinking water in their own homes.

We were able to help move the City of Flint from a jumble of 45,000 hand-written index cards to a data-driven modeling approach to locating likely lead lines, and now Flint residents have a user-friendly online map of up-to-date lead pipe locations. If Flint can identify its water pipe materials and its citizens can easily access this information, then the same can be done in other cities.

Our work in Flint demonstrates that we can use the data we have to find the 6-10 million lead pipes still lurking under homes across America, and that we can get the lead out, for good.