The Dept. of Solar Radiation Management

Is attempting to block the sun’s heat a good idea—or a reflection on our pathetic efforts to cut carbon emissions?

Solar Radiation Management (n.): a set of geo-engineering strategies intended to minimize global warming by reflecting the sun’s energy away from the earth.

Solar radiation management sounds like corporate-speak. (VP for Solar Radiation Management, anyone?) In fact, it’s one of the most controversial concepts in climate change mitigation.

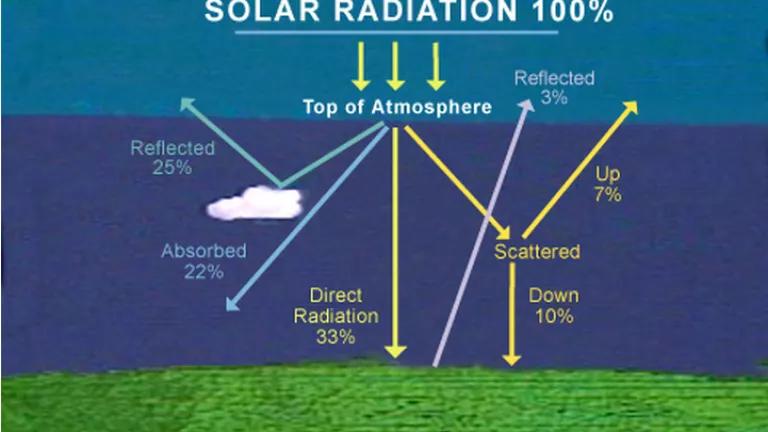

The idea is fairly straightforward. First, some Climate Change 101: About 30 percent of the energy arriving from the sun is reflected back out into space, mostly by clouds and ice. The planet—its seas, lands, creatures, buildings, etc.—absorbs the remaining 70 percent, and gases such as carbon dioxide and methane trap some of that heat within the atmosphere. So here’s the pitch for SRM: What if we could bounce more of the sun’s energy back into space in the first place, preventing it from ever getting trapped by the greenhouse effect?

How might we make that happen? One wildly impractical proposal is a network of space mirrors. The problem with this idea isn’t just that it sounds like something a fourth-grader would dream up—it would take a tremendous amount of energy to launch those mirrors into space. (Wasting energy by burning more fossil fuels is precisely what we’re trying to avoid.) Another option is to mist seawater into the air. Those white clouds would reflect solar energy before it reaches the darker, energy-absorbing ocean. This strategy has moderate support among SRM advocates.

To understand the most popular approach, though, think back to the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines, if you can remember it. (I envy your youth if you can’t.) The volcano spewed a huge amount of sulfur dioxide, a precursor of sulfuric acid. Within a year, the sulfuric acid layer stretched around the entire planet. Tiny droplets of sulfuric acid reflected sunlight back into space before it reached earth, and the planet’s temperature dropped by approximately 1 degree Fahrenheit for more than two years.

SRM advocates say we could do something similar—and without killing hundreds of people and displacing thousands more, as Pinatubo’s eruption did. We could fly high-altitude planes or float balloons capable of spraying sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere. (Other chemicals, such as titanium dioxide, are also under consideration.) To offset a doubling of atmospheric CO2, which represents a global temperature increase of between 1.5 and 4.5 degrees Celsius, researchers think we would have to inject around five megatons of sulfur dioxide annually into the atmosphere.

Five megatons sounds like a lot—and it is—but SRM enthusiasts point out that coal-fired power plants already emit nearly 55 megatons of sulfur. This is just a 10 percent increase on that number, and for a good cause.

Are you sold? Not so fast. There are many, many complications, and even the most open-minded conservationists are skeptical of SRM. For one thing, it’s largely unproven. Just because a volcano can do something doesn’t mean we can do it—especially in a controlled fashion. In addition, the effects of SRM are likely to vary by region. The process could make some areas colder than they currently are, depressing agricultural production. Russian farmers, for example, might have something to say about this. SRM might also diminish our motivation to reduce carbon emissions. That’s an issue because excess carbon causes many problems beyond higher temperatures. The oceans would continue to acidify, for example, killing off species like clams, oysters, and corals, and disrupting marine ecosystems.

For now, think of solar radiation management as the panic room of climate change mitigation. Few people really want to go there, but it’s still tempting to some, especially since our current rate of progress on carbon reduction suggests things could get pretty bad. Let's hope we can turn things around before it comes to that.

This article was originally published on onEarth, which is no longer in publication. onEarth was founded in 1979 as the Amicus Journal, an independent magazine of thought and opinion on the environment. All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of NRDC. This article is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the article was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the article cannot be edited (beyond simple things such grammar); you can’t resell the article in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select articles individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our articles.

Sea Level Rise 101

What Are the Solutions to Climate Change?

Climate Tipping Points Are Closer Than Once Thought