Goodbye, Ski Resort. Hello, Grizzly Bear Corridor!

After three decades of legal battles, the Ktunaxa Nation tapped into Canada’s newest conservation tool to protect Indigenous lands.

Frank Martin via Flickr

After a long hibernation, grizzlies are stirring in the Purcell Mountains as wildflowers begin to peek out of melting snow. If spring is a symbol of rebirth, it is especially so in the part of western Canada known as Qat’mak, or the Jumbo Valley, this year. The 170,000-acre area is now back in the care of the Ktunaxa Nation—an enormous environmental victory three decades in the making.

Since 1991, the Ktunaxa Nation, a tribal council made up of four bands of Indigenous peoples, has been fighting a bid to construct a massive ski resort on its ancestral lands in southeastern British Columbia. With 6,000 beds and year-round attractions, the Jumbo Glacier Resort would have been North America’s largest such destination and, with 5,000 feet of skiable mountainside, its highest in elevation. The proposal, put forth by Glacier Resorts Ltd., was akin to building a small town atop the glacier.

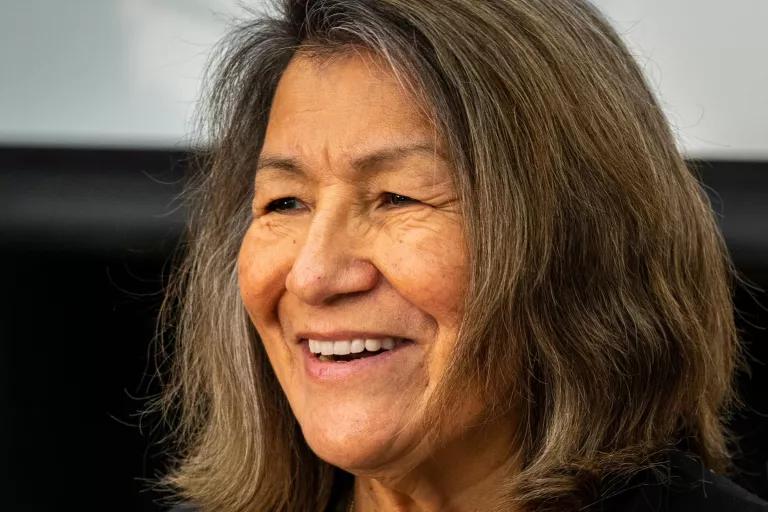

“We've been told from those that are knowledge keepers that this is a place of spiritual significance,” says Kathryn Teneese, chair of the Ktunaxa Nation Council. “It’s a special place, and we wanted to ensure that it continued to exist.”

The Grizzly Spirit

To the people who have lived in Qat’mak for 10,000 years, the region is more than picturesque snowcapped peaks, craggy glacier walls, and dense stands of pine. It’s also home to the Grizzly Spirit—a divine being not unlike one that a Christian, Jew, or Muslim might seek in a church, temple, or mosque. The Grizzly Spirit is a presence the Ktunaxa believe could be diminished and driven away by runaway development like a ski resort.

Qat’mak is special for grizzlies in the flesh, too. According to Michael Proctor, an independent research ecologist who’s been studying the bears of this region for about 25 years, the Jumbo resort would have risen in the middle of the Purcell-Selkirk population. At 600 bears strong, this group is actually doing quite well, says Proctor, but it is “sort of the anchor or source population for all the fragmented populations just to the south.”

If you think of the grizzly’s current habitat, from Yellowstone National Park all the way up into central Canada, it may seem vast. But it’s actually more like a cracked windshield, says Proctor, who is also the lead researcher for the Trans-border Grizzly Bear Project.

“What used to be a big, solid population is now broken up by patterns of human settlement and transportation corridors,” he says. And when bears try to move across that patchwork of roads, towns, and housing developments, it can lead to untimely death.

These lumbering giants once roamed across the entire western United States and Canada, much of the Great Plains, and even parts of Mexico. Today the grizzly’s U.S. range has shrunk to just 2 percent of its former size, and most of its southern populations are dwindling as development fragments more and more of their habitat. (Canada lists grizzlies as a species of special concern, while the United States considers the species to be threatened, though many conservationists say the bears need more protection than that status provides.)

Proctor says decades of research have shown that highways, towns, and developments have a significant effect on bear populations. And the ski resort would have brought all those threats together in one great big blob. “We just didn’t want to fragment that population any more,” says Proctor, who argued against the resort in a 2010 letter to the provincial government.

Kathryn Teneese, chair of the Ktunaxa Nation Council

Pat Marrow

Persistence Pays Off

After years of court proceedings that challenged everything from the resort’s environmental impact assessment to the provincial government’s disregard for Indigenous spiritual rights, the battle for Jumbo landed in Canada’s Supreme Court in 2017. The Ktunaxa Nation lost.

But its members did not give up.

Right around the same time that the tribes’ legal challenges hit a glacier wall, a political scientist named Eli Enns reached out to the Council. Enns is a member of the Nuu-chah-nulth people on Canada’s Pacific coast and president of the Iisaak Olam Foundation, an environmental organization.

The Canadian government had just pledged to protect and manage at least 17 percent of the nation’s land mass by 2020. And to help meet that goal, the government had begun making funds available to Indigenous groups interested in purchasing land rights for the establishment of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs). The terms of IPCAs vary from region to region, but they all lead to Indigenous control of natural resources. In 2009, Enns had used the program to help his people establish legal rights over the Ha’uukmin Tribal Park on Vancouver Island.

Earlier this year, the Ktunaxa Nation was able to secure $16.2 million from the Canadian government, with an additional $5 million coming from conservation organizations and private companies, such as Patagonia. The Ktunaxa used the money to buy out the resort’s investors. It turned out, too, that the years of court battles had not been in vain. Amid all the litigation, the resort’s environmental assessment certificate had expired. “So they really didn’t have too many options available to them,” says Teneese, the Council chair.

It was a win for the Ktunaxa Nation and the rest of the community, which had also been fighting the development, sometimes taking to the streets to do so. “I have lived in this valley since 1985,” says Proctor. “Even among the non-Indigenous population, this decision was applauded almost universally in the area where I live.”

Just the Tip of the Glacier

The Ktunaxa’s IPCA is just one of 27 to receive funding in recent years, and many more are on the way. “There are 630 Indian bands across Canada,” says Enns. “And I would say with about 99.9 percent confidence that each one of those bands has a place in their area that they want to protect.”

For Teneese, though, the decision brings with it some complicated emotions. On the one hand, the long fight is over. Her people have won. Now they can focus on the hard work of deciding what comes next for the land. But there’s also a feeling of great irony.

“We had to buy it,” says Teneese. “They weren’t going to be building what we considered to be a monstrosity, [but] they were still getting something out of it.”

In the end, she says it was the Council’s only way forward. With any luck, their experience will help other bands establish their own IPCAs, protecting grizzly bears elsewhere as well as countless other species across Canada.

To the bears waking up right now in the Jumbo Valley, nothing will seem to have changed. And yet, everything has.

This article was originally published on onEarth, which is no longer in publication. onEarth was founded in 1979 as the Amicus Journal, an independent magazine of thought and opinion on the environment. All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of NRDC. This article is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the article was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the article cannot be edited (beyond simple things such grammar); you can’t resell the article in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select articles individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our articles.

In Planning for Climate Change, Native Americans Draw on the Past

A Tale of Two Forests: A Tour Through Canada’s Boreal

Mapping a Future for Boreal Caribou