In These Brightly Colored Landscapes, the Sharp Edges of Industry Collide with Nature’s Curves

Judith Belzer’s oil paintings of bridges, dams, canals, and ports both romanticize and question humanity’s efforts to tame our natural systems.

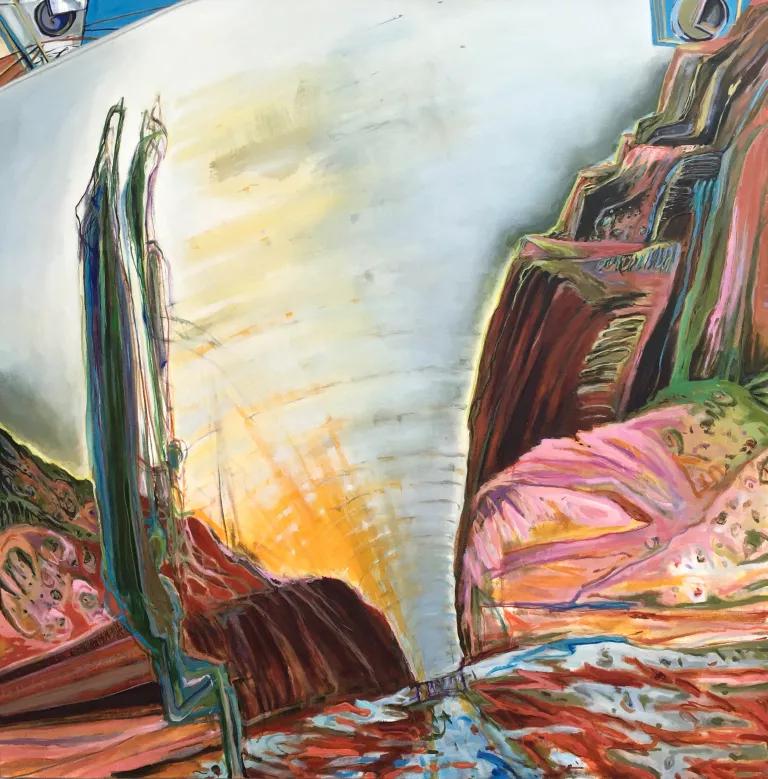

“HalfEmptyHalfFull 11,” 2017, by Belzer

Judith Belzer’s art took a radical turn after she moved from rural Connecticut to northern California in the early 2000s. At first she stayed fascinated with trees. She painted intimate oil-on-canvas studies that probed the inner life of live oaks and eucalyptus, imagining herself as an ant “crawling along the bark of the tree and then somehow penetrating to the tree’s interior,” she wrote at the time. But on walks in the hills of Berkeley, the wide panorama of San Francisco Bay opened before her and her perspective soon shifted.

Belzer studied the port of Oakland in the near distance—its freeways, oil refineries, and bridges—and then the Golden Gate National Recreational Area and the Pacific Ocean beyond. “The biggest shock to me, moving to the West Coast, had to do with scale and the way I felt standing in the landscape there. It meant I felt much smaller,” she says with a laugh.

In Belzer’s eyes, the traditional categories of landscape—mountain and maritime and rural scenes—would blur together with industrial vistas in a mash-up of water, sky, concrete, metal, and earth. So she began capturing this sight, or rather the sensation of it, in paintings that combined the imagery of industry and infrastructure with the shapes and contours classically associated with the natural environment.

Belzer’s “From the Anthropocene” landscapes (the series title a reference to the current human-dominated geological period) pulse with a staccato energy that courses through elaborate pathways rendered in the bright colors of plastic packaging and gadgetry. The artist describes the series’s twisted overhead perspective as both a reflection of her physical vantage point overlooking San Francisco Bay and a metaphor for the precariousness of the situations depicted. “From my point of view, truly there was no steady ground on which to stand to look at this,” she says.

As unstable as Belzer’s California landscapes can be, they also project a vitality and dynamism that hint at the hubris of humanity’s sense of ownership of the earth and its resources. Renny Pritikin, chief curator of San Francisco’s Contemporary Jewish Museum, who chose three of Belzer’s paintings for a recent group show of California Jewish artists, describes them as “semiabstract but recognizable paintings of the waterfront that say: Look what we’re doing to paradise. We’re taking one of the most beautiful places in the world and turning it into an industrial park.” At the same time, he adds, the paintings are so full of color and energy that they can also be seen as celebrations of life. “Contradictory points can both be true,” Pritikin says.

Belzer’s interest in the Anthropocene took her to Central America in 2015, where the planet’s largest constructed waterway, the Panama Canal, was being widened and deepened in response to plans, since abandoned, to build a rival canal in Nicaragua. Some of Belzer’s “Panama Project” paintings are now on exhibit at the Nevada Museum of Art’s Center for Art and Environment in Reno.

From the viewpoint of the canal’s glassy waterline, the paintings show blank hulls of cargo ships as tall as skyscrapers as they methodically transit the canal like “Darth Vader moving through the water,” as Belzer describes one massive vessel carrying cars from factory to market. If we have historically looked to nature for a sense of wonder, she says, “now we’ve constructed these man-made landscapes that are a new place to look for that awe. We’ve outsized ourselves by our own hand.”

Recently Belzer found another potent symbol of humanity’s power in the massive dams of the American West. Built on a scale as large as nature itself, they appear in Belzer’s “HalfEmptyHalfFull” series as a blunt expression of the American notion of Manifest Destiny running up against the realities of climate change and shifting economics.

“I’m sensing that as our climate changes and there’s less water, many of these dams are going to be decommissioned,” she says. “I think of them as monuments that will remain for hundreds of years, because many of them are way too big to take out,” she says. “They will be like leftovers in the landscape—reminders of the whole idea that these resources were thought to be divinely ours and endless, too.”

As in all of her work, Belzer’s intent is not to prescribe answers but to provoke thought. “I think of these scenes as a very complex set of relationships that I wouldn’t say are all good or all bad, or all beautiful or all hideous,” she says. “I’m just really interested in inviting people to look and to ask questions.”

“Judith Belzer: The Panama Project” is on view at the Nevada Museum of Art’s Center for Art and Environment in Reno, Nevada, through November 11.

This article was originally published on onEarth, which is no longer in publication. onEarth was founded in 1979 as the Amicus Journal, an independent magazine of thought and opinion on the environment. All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of NRDC. This article is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the article was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the article cannot be edited (beyond simple things such grammar); you can’t resell the article in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select articles individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our articles.

Biodiversity 101

What Biden Should Get Done on Day One (or Close to It)

The Overlooked Importance of Penguin Poop, Fulmar Feces, and Gull Guano