The Drinking Water Crisis That North Carolina Ignored

For decades, DuPont dumped toxic PFAS into North Carolina’s Cape Fear River. Today, the local community is suffering the health consequences—and fighting back.

The Chemours Company discharges waste into the Cape Fear River, polluting the water supply downstream.

Jeremy Lange

When the Wilmington, North Carolina, StarNews broke a story in 2017 about the rampant contamination of the region’s drinking water supply by a chemical called GenX, Tom Kennedy had just finished four months of chemotherapy for his stage 2 breast cancer. During the radiation treatment that followed, Kennedy, then 45, learned that the cancer had metastasized to his brain, newly classifying him as a stage 4 terminal patient with 6 to 12 months to live. Four years later, with some 60 rounds of chemotherapy under his belt, he’s still going strong.

But also four years later, the Cape Fear River watershed—which supplies drinking water for Kennedy’s family and around 350,000 other North Carolinians—remains contaminated with the perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) that DuPont, and its spin-off, Chemours, dumped into the river for more than four decades.

“I don’t know if it can ever be proven,” Kennedy says, “but I’m pretty certain that the PFAS contamination is what led to my cancer.”

PFAS are used, often superfluously, in everyday products like nonstick cookware, carpets, food packaging, stain repellents, and water-resistant clothing. The synthetic compounds are also commonly found in firefighting foam and gear, which has led to the contamination of most military bases and airports. GenX, which DuPont began producing in 2009, is merely one of the many thousands of these “forever chemicals” that don’t break down in the environment and, instead, can bioaccumulate in the bodies of humans and wildlife. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), PFAS can be detected in the blood of nearly every American.

La’Meshia Whittington-Kaminski of the NC Black Alliance and Advance Carolina at the 2020 Women's March, speaking out against PFAS and environmental devastation that has ravaged her community

Courtesy of La’Meshia

Breathing contaminated air and eating contaminated food can also expose people to these chemicals. La’Meshia Whittington of the NC Black Alliance and Advance Carolina notes that low-income people of color face greater risks of exposure, since they’re not only more likely to live near polluting facilities but also more likely to eat fast food meals that come in PFAS packaging, live in rental units with PFAS-laden carpeting, or drink from contaminated water supplies. At the same time, these populations are less likely to be able to afford bottled water or the expensive filtration systems that effectively remove PFAS contamination from their water. Whittington says, “It’s the historical legacy and atrocity of cumulative impact that we’ve had to deal with.”

Just a few miles from Wilmington, in Leland, Kara Kenan of Going Beyond the Pink works with the local breast cancer community and has been battling the disease herself since 2013. More recently, her mother and stepfather together developed three cancers, including one very rare form, within a year of each other. “You have these very healthy individuals all of a sudden getting these cancers,” says Kenan. “It was right around the same time that we started learning about what was in the water, but I hadn’t connected the dots that they might be related yet.”

Kara Kenan and her family while she was going through treatment for breast cancer

Courtesy of Kara Kenan

Although the human health impacts of PFAS are a relatively new area of study, a 2021 CDC report found that exposure to PFAS, even at very low levels, can cause thyroid problems, fertility issues, asthma, and more. Indeed, scientists suspect there is a possible thyroid cancer cluster in the Wilmington area, about 90 miles downstream from Chemours’ Fayetteville plant.

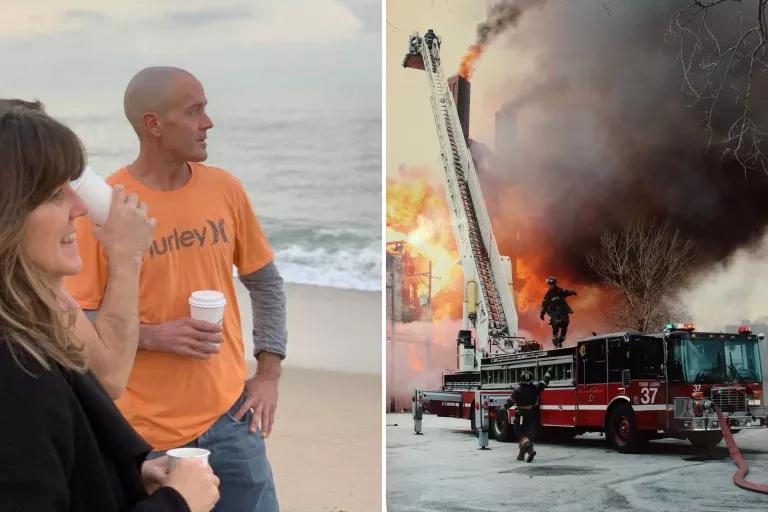

During a 2018 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency listening session in Fayetteville, Dana Sargent recalls community members giving powerful testimonies, holding photographs, and speaking through tears about their rare kidney diseases, miscarriages, and other health issues. Sargent, who is the executive director of Cape Fear River Watch, also shared a personal story. Her brother, Grant, died at age 47 in late 2019, two years after being diagnosed with glioblastoma, an aggressive brain tumor. Sargent says she’ll always wonder if his PFAS exposure as a Chicago fireman and former Marine caused his cancer. The EPA didn’t even bother to record the session. “We’re not asking them to do anything but their job,” she says. “The whole country knows PFAS are bad. And yet we sit with no regulation on these companies.”

From left: Dana Sargent and her brother Grant; Grant at work as a firefighter in Chicago

Courtesy Dana Sargent

While other states, like Michigan and New York, have begun limiting the amount of PFAS allowed in drinking water, North Carolina has done very little to protect its residents, says NRDC attorney Corinne Bell. State Representative Pricey Harrison introduced three bills last year that would regulate PFAS, but they failed to advance. In April 2021, she tried again, filing bills that call for a statewide ban of PFAS, mitigation measures, and health-impact studies, but she doesn’t expect a ban on the toxic chemicals to go anywhere.

“It might pass in California, but not here,” she told local news channel WECT, adding that she still hopes the state could begin limiting the allowable uses of PFAS. State Representative Deb Butler, who has worked closely with Harrison on this issue, also knows she’s fighting an uphill battle. She sponsored a bill that would require Chemours to pay for the $50 million granulated activated-carbon system the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority is installing to filter its drinking water supply.

The North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ) filed a lawsuit against Chemours in 2017—but only in response to bad press—and last fall, the state attorney general filed another. And yet, North Carolina is currently reviewing its water quality standards, something it does every three years, but not one rule for PFAS pollution is even up for consideration. “People know they’re being poisoned, but the state isn’t doing much about it,” Bell says.

So residents have been taking matters into their own hands. In July 2018, Cape Fear River Watch, represented by the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC), sued the NCDEQ to force Chemours to immediately stop polluting the Cape Fear River. The following month, the pair also filed a federal lawsuit against Chemours for violating the Clean Water Act and Toxic Substances Control Act, but it was dropped later in the year as part of a $13 million settlement among the NCDEQ, Cape Fear River Watch, and Chemours. The settlement resulted in a consent order that required Chemours to cease its discharges and add scrubbers to its smokestacks to prevent airborne PFAS pollution. The outcome is a critical step in preventing future PFAS pollution, but NCDEQ has had to fine the company for not complying with the order, and its past contamination, still lingering in the water, soil, and peoples’ bodies, remains unaddressed.

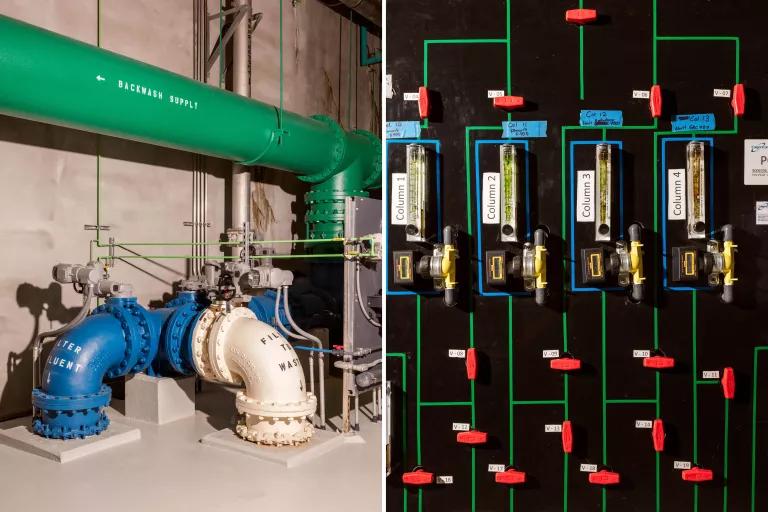

From left: The banks of the Cape Fear River, 50 miles downstream from the Chemours plant; a basin at the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority, which is responsible for all the drinking water for the city of Wilmington

Jeremy Lange

Emily Donovan understands how all-consuming the fight can be, and how overwhelming it can feel when taking a giant chemical company to task. She heads a volunteer watchdog group called Clean Cape Fear, which was founded in the wake of the StarNews investigation and after Donovan’s husband, David, discovered he had a brain tumor.

From left: Inside the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority water treatment plant; the plant has been testing new filtration techniques for GenX contamination.

Jeremy Lange

“We were the story that got ignored,” Donovan says. “These corporations knew exactly what they were doing, but we were intentionally overlooked by those who were in the know.” While the StarNews story first brought the issue to the public’s attention in 2017, North Carolina’s agencies and elected officials likely knew about the PFAS problem at least a decade earlier, when government scientists published a study on it. This is the problem with regulatory systems that prioritize private profit over public safety. “The chemical industry has for decades found the weaknesses within our governing bodies—which are supposed to protect us—and manipulated them to their strengths,” Donovan says. “We're allowing corporations to sidestep ethics and morality, and we're doing it at the expense of humanity.” Her work, she says, is focused on “being a voice of conscience.”

From left: Emily Donovan, head of Clean Cape Fear; donated water jugs fill the PTA supply closet at the school of Donovan's children.

Courtesy of Emily Donovan

Clean Cape Fear’s fight extends from Big Chemical and the state all the way down to the local public education system, including the school Donovan’s twins attend. Just west of Wilmington’s Hanover County sits Brunswick County, which a 2019 Environmental Working Group study found to have by far the highest PFAS levels in its tap water out of the 44 places it analyzed across the country. After much pushback from school officials—including them even rejecting a $200,000 grant Donovan secured to install a water filtration system—they finally relented. Earlier this year, public schools in Brunswick and New Hanover counties began adding filling stations that filter water using reverse osmosis, a method that local scientists have found reduces PFAS levels by 94 percent or more.

In May, Emily Sutton of the Haw River Assembly took water samples to test the tributary for PFAS.

Courtesy of Emily Sutton

But the North Carolinians living downstream from the Chemours facility aren’t the only ones in harm’s way. Farther north in the watershed of the Haw River, a Cape Fear tributary, PFAS contamination is also a problem, particularly in the 4,200-person town of Pittsboro, a bedroom community for the Research Triangle that, due to a major development project, is expecting to welcome up to 60,000 new residents in the coming years.

“I will forever be kicking and screaming about precautionary principle,” says Emily Sutton, Haw riverkeeper for the nonprofit Haw River Assembly, which has partnered with local scientists studying PFAS while focusing on its own advocacy and education efforts. A company operating under the precautionary principle would have to vet and test chemicals, and prove they’re safe before using or emitting them. “But it works exactly the opposite way,” she says. “Chemical companies can create these compounds, without any regard for impacts to human health or the environment, and discharge them until proven guilty.”

Public health advocates would like to see more research conducted on the impacts of PFAS, with Chemours footing the bill, but they stress that the dangers are clear enough right now to take decisive action. “We have enough information to know that this pollution is bad, that it needs to stop being put into the environment, and that we need to clean up what’s already there,” says Bell. What we don’t know is whether North Carolina is going to finally step up and protect its people.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Wilmington’s Battle With GenX, a Dangerous Teflon Chemical

“Forever Chemicals” Called PFAS Show Up in Your Food, Clothes, and Home

The Fight for Safe Drinking Water Doesn’t Start at the Top